Read Part 1 here

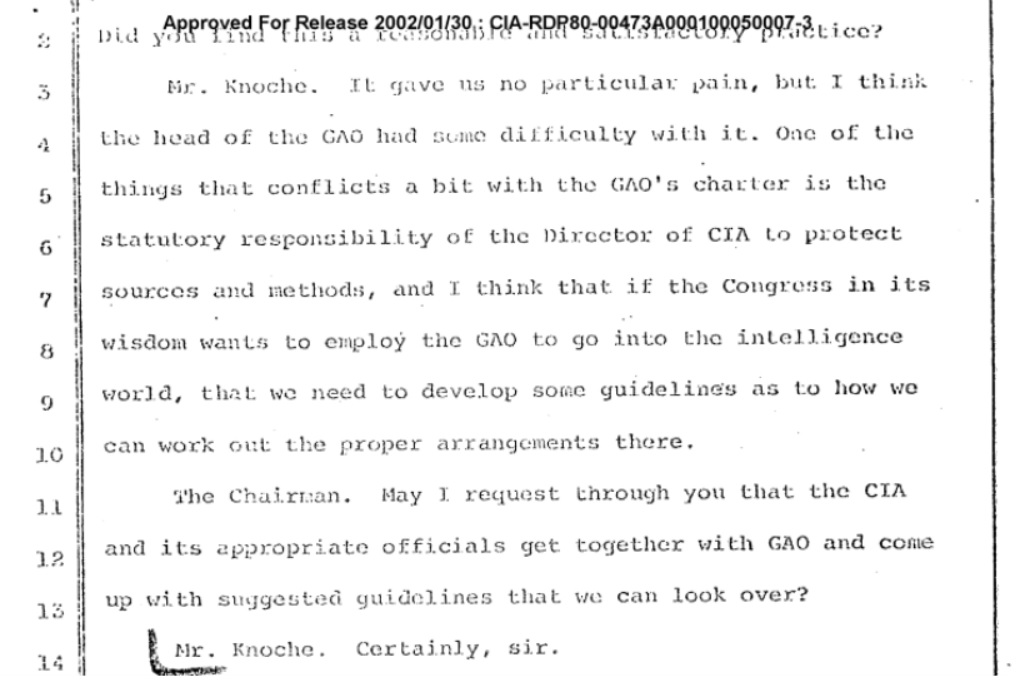

During the Pike Committee hearings, it was requested that the Agency get together with the GAO to work on guidelines to cover their relationship on it.

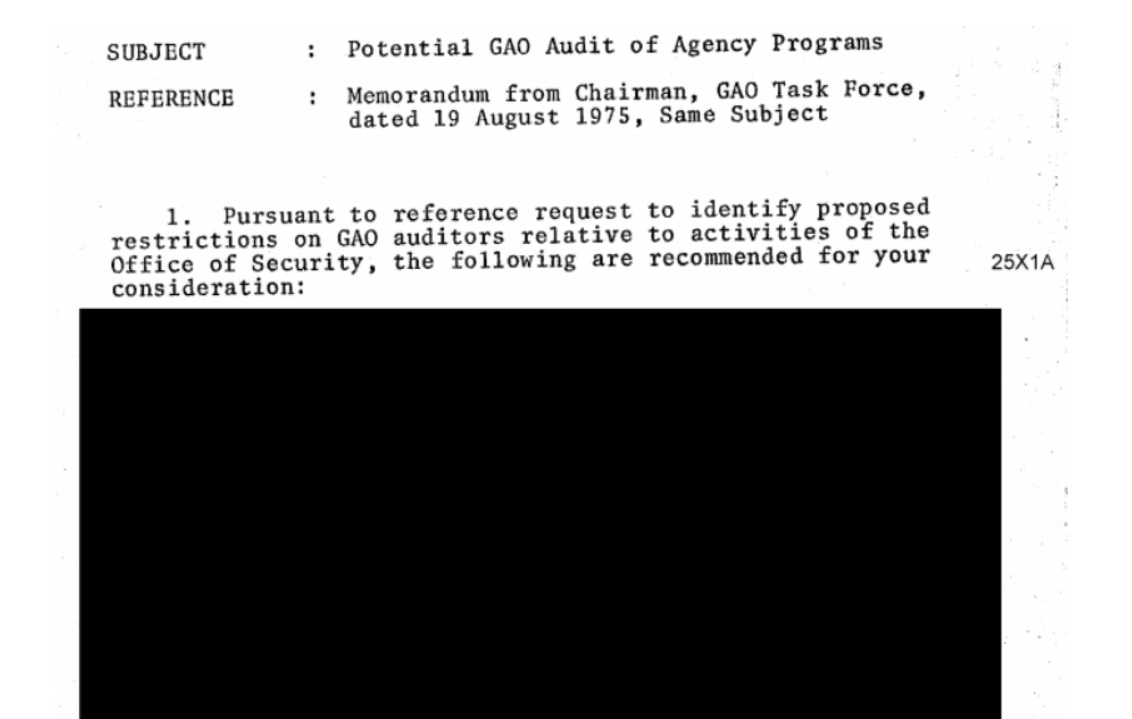

Around the same time, the Agency created an internal Task Force to deal with the GAO question. The Task Force, headed by Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) Director of Finance, would make a number of recommendations to limit the type of audit that might be performed by the GAO. Those recommendations remain classified by CIA, which claims they are protected as one of the agency’s sources and methods. It’s likely that this is as false now as it was when the Agency claimed the same thing regarding the CIA-GAO letters.

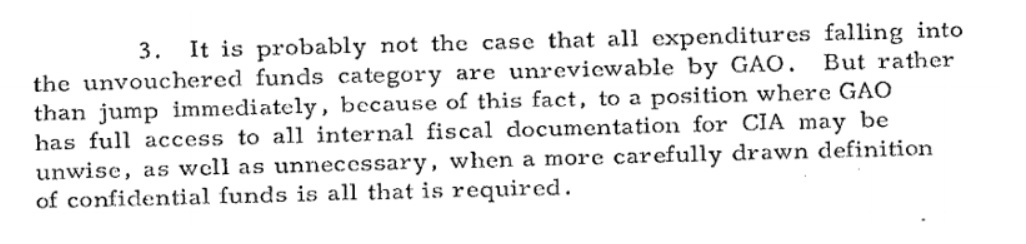

The recommendations of the Task Force were all contingent on Congress forcing CIA to resume some form of audit activity, none of them assumed that the Agency would take such measures willingly. In the process of editing of the GAO Task Force’s report and recommendations, CIA’s Office of General Counsel conceded an important point which contradicts that Agency’s stance and justification for denying GAO’s auditors access to a significant portion of the Agency’s activities. According to CIA’s lawyer, “it is probably not the case that all expenditures falling into the unvouchered funds category are unreviewable by GAO.” For decades, however, CIA had maintained this as an absolute and as a reason to prevent GAO from completing a more comprehensive audit.

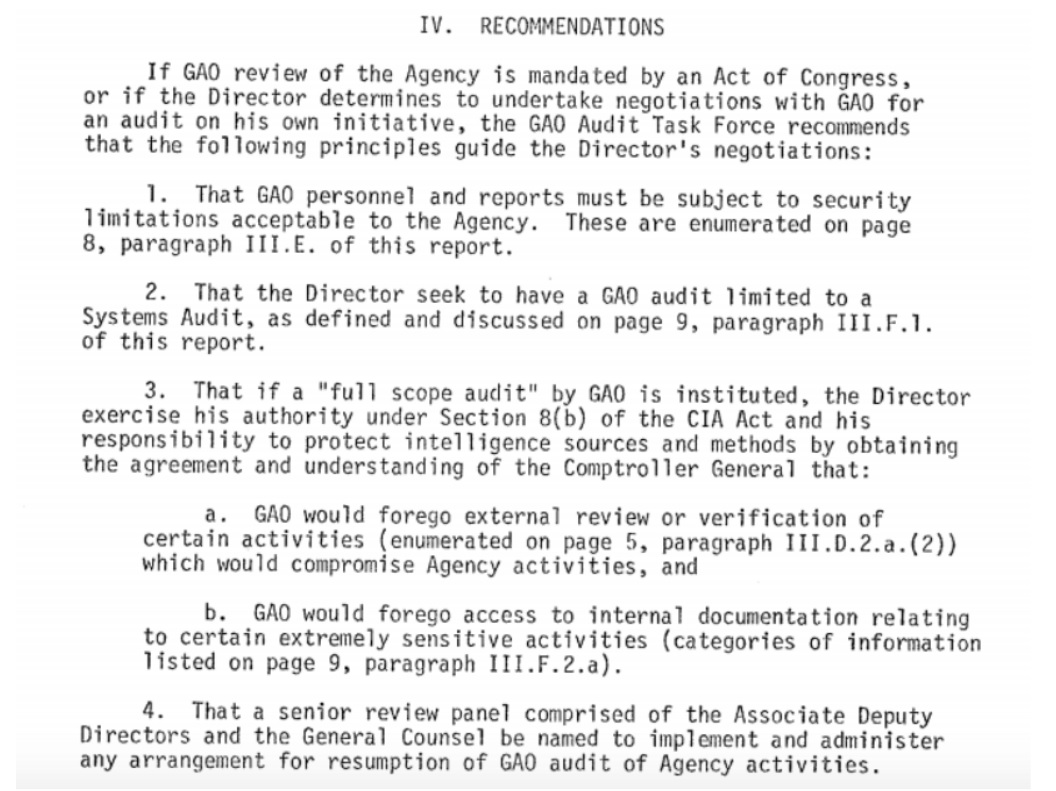

The GAO Task Force’s recommendations requested a number of points that would prove problematic for advocates of oversight. Among other things, GAO would sometimes be required to “forego external review or verification” as well as being required to “forego access to internal documentation” for sensitive activities. The Task Force also recommended that an additional panel be created, made up of CIA’s lawyer and Associate Deputy Directors, to determine specifics and administer the specifics of any GAO audit.

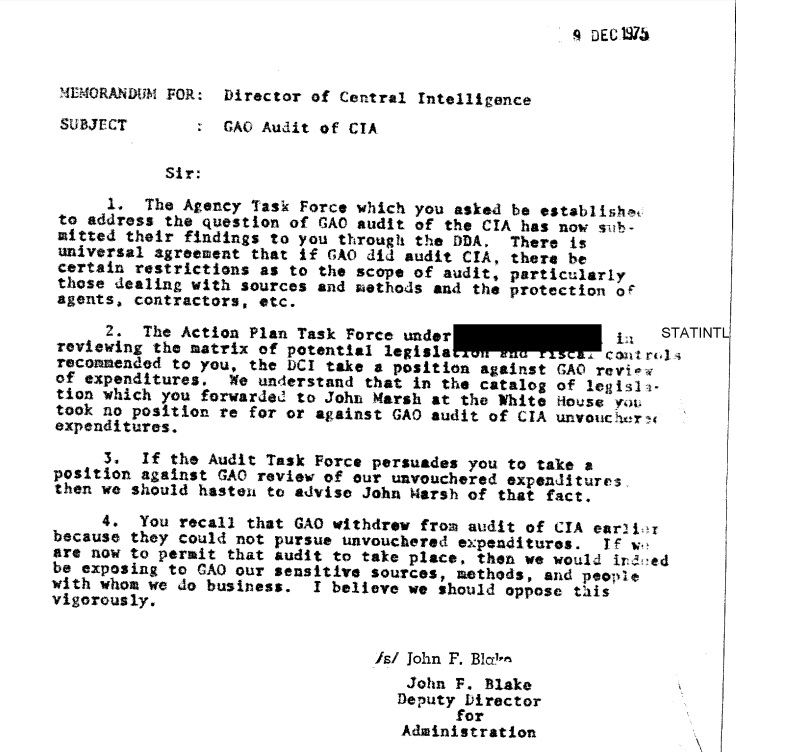

It was the hope of the Agency’s Deputy Director for Administration that the GAO Task Force’s report would convince the CIA Director to take a position against GAO review and audit of the Agency’s unvouchered expenses.

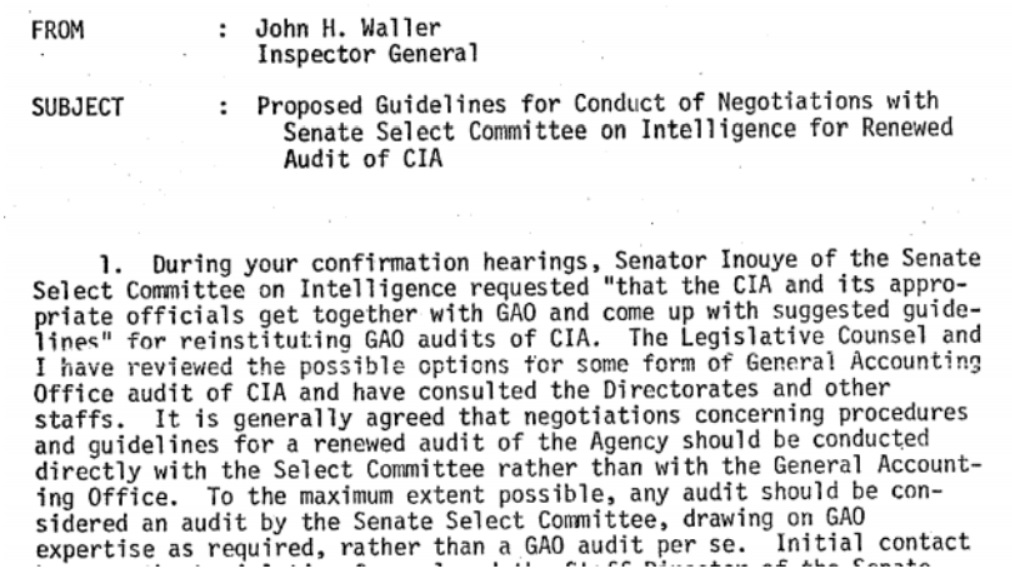

John Waller, CIA’s Inspector General, would go a step beyond the Task Force’s recommendations for handling negotiations relating to a resumption of GAO audits. Waller proposed that the negotiations cut out the Government Accountability Office entirely. Rather than deal with the GAO while discussing the terms of GAO audits, Waller thought the Agency should discuss the matter with the Senate Select Committee directly. He also suggested that any audit involving the GAO be considered under the auspices of the Senate rather than the GAO itself, which might set a precedent.

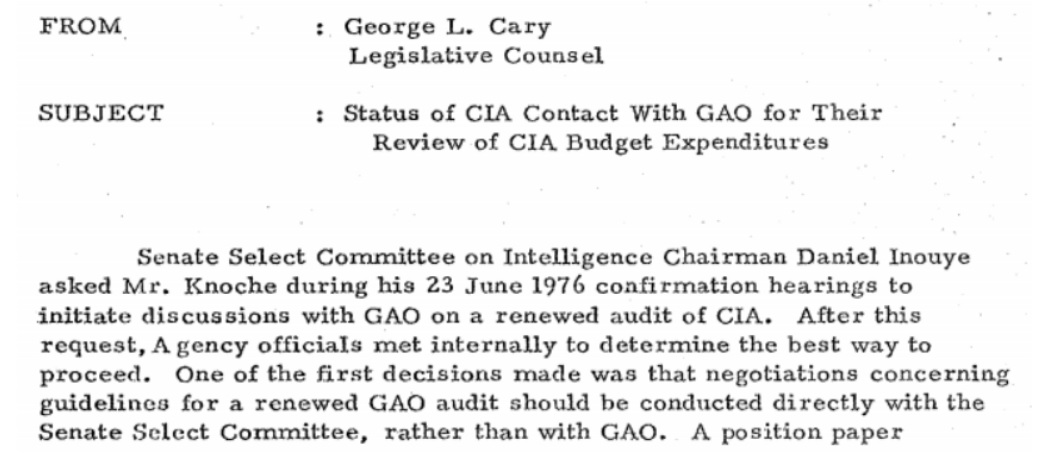

A subsequent memo explains that the decision to cut the GAO out of the negotiations was one of the first decisions made.

According to Agency History and former head of CIA’s History Staff, it was not the Task Force’s recommendations, the negotiations or the delays that killed the reform recommendations - it was the censorship. Haines wrote that “all these reform recommendations were attempts to improve the organization, performance, and control of the IC without adversely affecting US intelligence capabilities. Yet, in the turmoil surrounding the controversy over whether to release the report, the recommendations were ignored, forgotten, or simply lumped in with the report as outrageous and missing all the points.”

Another Agency history, referencing a draft of a CIA study, would note that “Senator Inouye also reopened the issue of GAO audits, pressing both the Agency and GAO to negotiate ground rules allowing audits to be reinstituted. These efforts continued sporadically during 1977 and 1978, making occasional headway but never coming to fruition.” The guidelines on GAO access, produced in 1979, may also have had something to do with the failure to meaningfully institute any of these reforms.

According to a memo from CIA’s Deputy Legislative Counsel, the guidelines were mostly one-sided. They explicitly did not grant GAO any greater authority for access or constitute an agreement or contract which was binding on the Agency.

In contrast, it seemed that the guidelines were binding on GAO and imposed a number of new explicit limitations which would apply in the event of a GAO review. Of primary importance to CIA was their authority to protect information matching any of the 126 aspects of intelligence sources and methods from disclosure. The guidelines also limited GAO’s access to anything concerning intelligence activities to instances where GAO had a “statutory right of access” or where a Congressional committee had jurisdiction. The standard of refusing to give GAO access to information except where a Congressional committee had jurisdiction becomes additional significant considering their later refusal to provide any information to the GAO if a Congressional committee did have jurisdiction.

The guidelines also limited GAO’s access and right to eliminate a number of CIA’s activities and products. According to the memo, the guidelines eliminated GAO as a conduit to congressional committees and as determinators of the quality of various intelligence products. Instead, GAO would primarily access CIA’s information to evaluate the quality of GAO’s own work. A handful of other restrictions discussed in the guidelines apparently furthered reduced CIA’s obligations to the GAO, similarly reducing CIA’s time commitment.

Whether because of the restrictive guidelines or, as CIA’s own historian suggests, because of the censorship of the Pike Report, GAO continued to be denied any meaningful ability to audit CIA or aid in Congressional oversight. Several years later, a CIA memo would refer to this as them successfully “holding the GAO and their armies of auditors at bay.” These new terms would later prove useful in blocking GAO probes of CIA’s activities and the quality of its work.

A FOIA request has been filed for a copy of the guidelines on GAO reviews of CIA. In the meantime, you can read portions of one of the drafts of the GAO Task Force’s report and other associated memos below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via C-SPAN