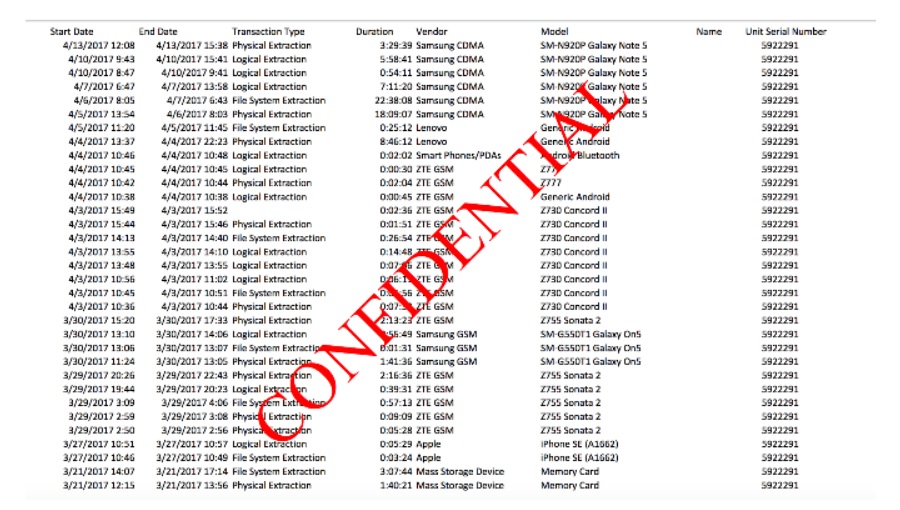

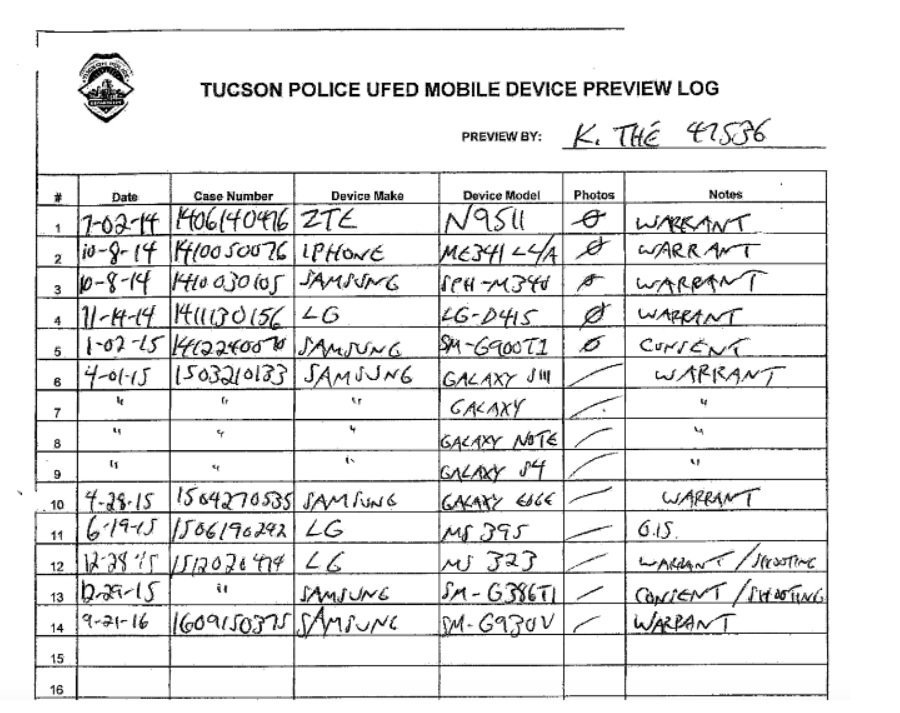

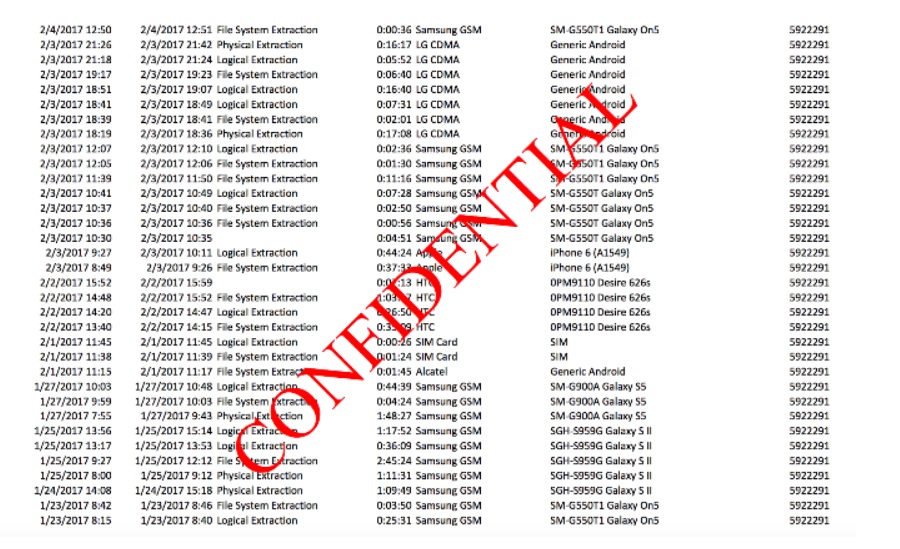

Mobile phone forensic extraction devices have been a law enforcement tool for years now, and the number of agencies using them is only rising. As part of an ongoing investigation, we have finally been able to turn up some usage logs of this equipment, from Tulsa Police Department and Tucson Police Department. While the logs do not list the cause of the crime or any other notes about why the phone was being searched, it does list the make of the phone, the date, and the type of extraction.

As an aside, there are three types of extraction. Physical extraction is what happens when the phone is connected via USB cable to the extraction device and its contents downloaded as copies of the phone’s files. A logical extraction is done using the phone’s corresponding API. A file system extraction is more or less a physical extraction that uses what is called the synchronization interface of a phone to access the phone’s memory system. This is a way to access deleted and hidden data.

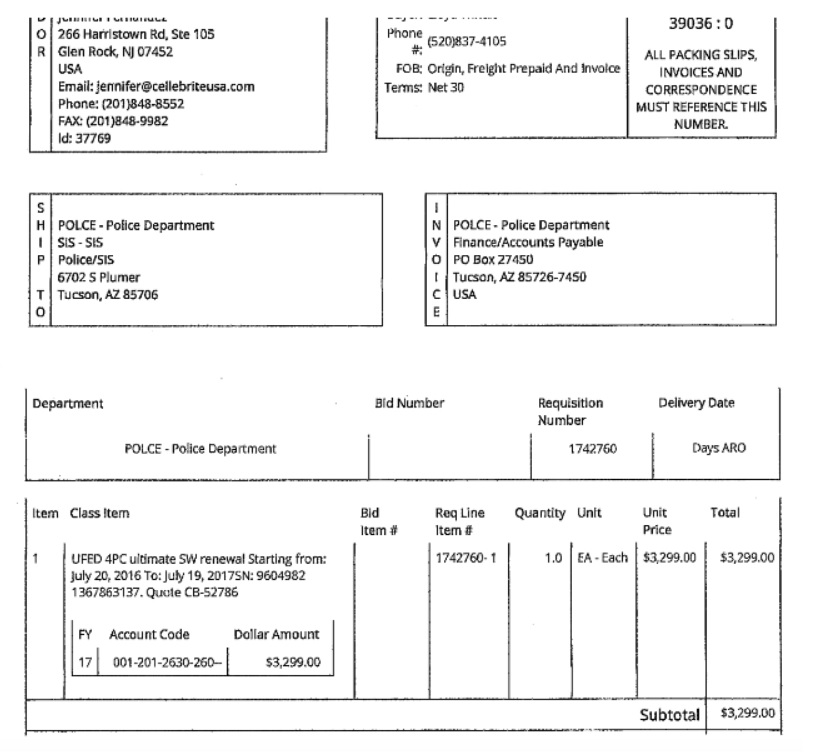

First, let’s go over what extraction devices are being used here. Tucson PD opted for the brand that is arguably the worldwide leader in mobile device forensics, the Israeli company Cellebrite.

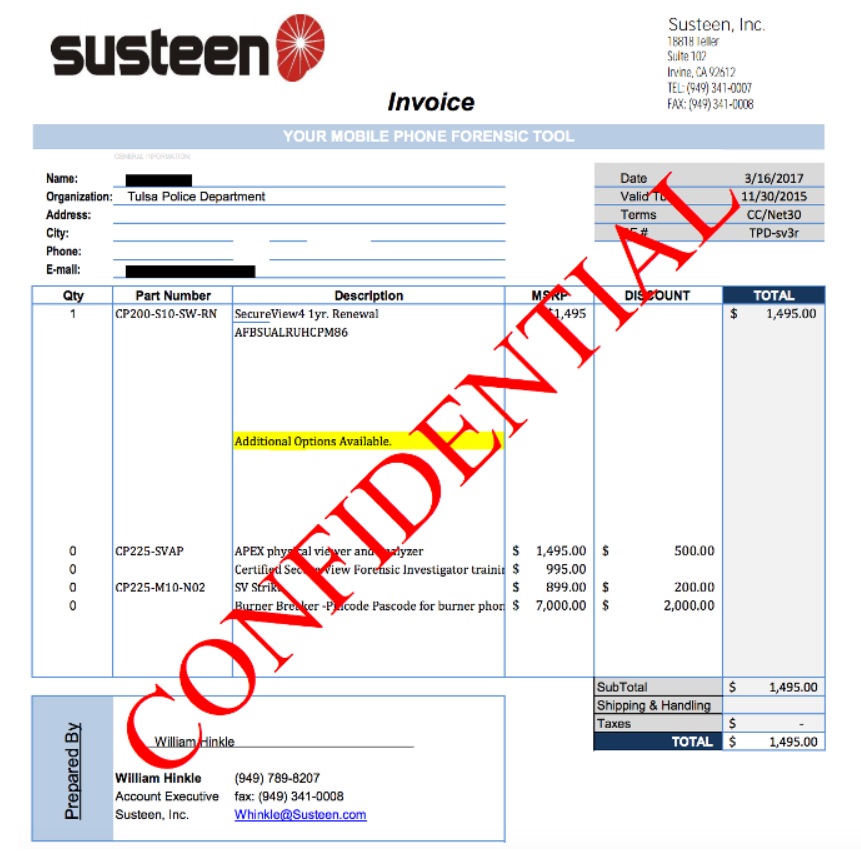

Tulsa Police Department however opted for a few different models - they purchased two different password breakers from Teel Technologies in 2015, and in March 2016 gave about $1,500 to Susteen for their SecureView extraction device (SecureView was the product Susteen created when the FBI requested they create a more advanced extraction device for them). It does its work instantly, and has an incredible reach into a phone’s data. They renewed this contract in 2017.

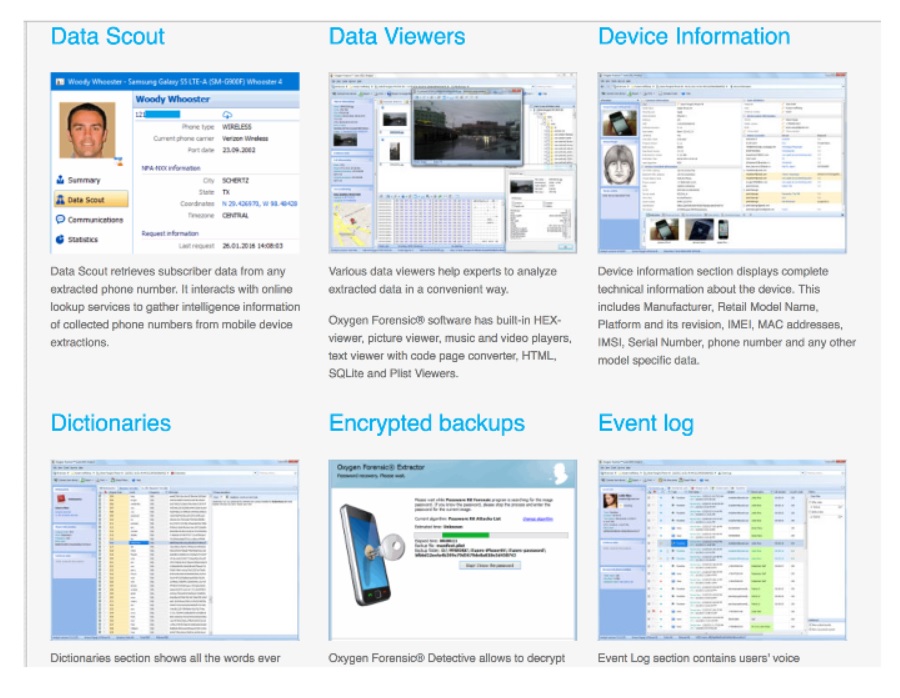

In August 2016 they also purchased the Detective extraction device from Oxygen Forensics. Oxygen is much less common than Cellebrite, from what we have found.

From Oxygen’s website though, it looks to be just as potent, if not more so. Included are a dictionary tool to search for every word ever entered into the device, a social connection mapper so all of the phone user’s relationships are neatly charted, a geo-location mapper to see where the person has been going, and many other tools to make cracking all that data more manageable and efficient.

The kicker really is how often these are being used - it is simply really hard to believe that out of the 783 times Tulsa Police used their extraction devices, all were for crimes in which it was necessary to look at all of the phone’s data. Even for the 316 times Tucson PD used theirs in the last year, it is still a real stretch to think that some low-level non-violent offenders weren’t on the receiving end. There are some days where the devices were used multiple times - Tulsa used theirs eight times on February 28th of this year, eight again on April 3rd, and a whopping 14 times on May 10th 2016. That is a whole lot of data that Tulsa was able to tap into, and we aren’t even able to understand the why.

One “preview sheet” we received from Tucson had a column for whether they received a warrant to crack into the phone, or whether the user gave them consent. It is easy to imagine a scenario where someone doesn’t want to risk angering police by refusing consent, or even just didn’t fully understand what they were consenting to.

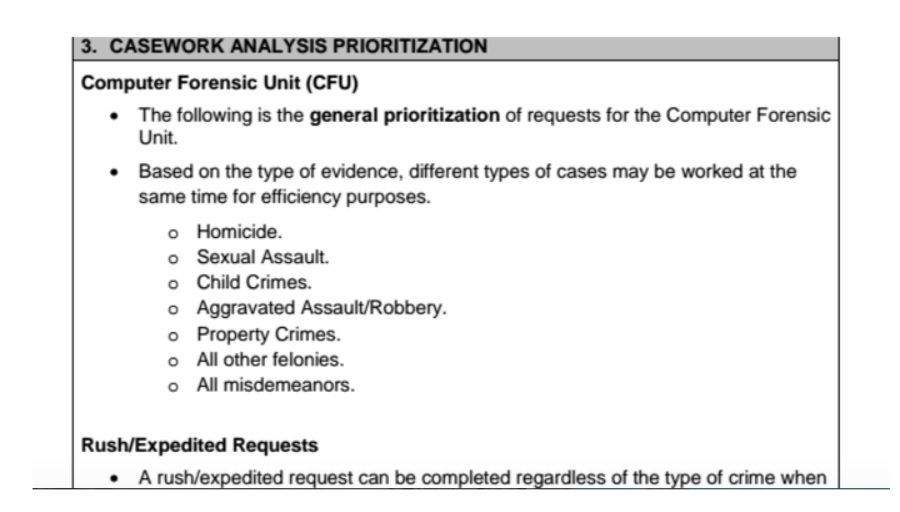

While we also have asked for departmental policies regarding the use of this equipment, we have only received one, from Mesa Police Department in Arizona, that has any kind of guidelines about what kind of cases these can be used in. And even that was terribly broad, basically allowing its use on pretty much any kind of crime.

While there are some kinds of cases where this technology is absolutely useful and often necessary, there are also many where this could be a violation of civil liberties, relinquishing a huge amount of private information for a crime that does not warrant that kind of invasive investigation. Again, from the numbers we are looking at here, it is hard to imagine that that isn’t happening to some degree.

The kinds of phones being cracked is also interesting, as there is much debate about whether these devices can crack an iPhone 6 or 7. While there were no instances of iPhone 7’s being cracked, several 6’s were tapped into by both Tulsa and Tucson PD’s.

The technology is controversial for a number of reasons, chief among these are concerns that protesters and activists who have been arrested at an action may be subject to extensive, and likely illegal phone searches - other people’s information will surely get caught up in this dragnet, creating a civil liberties nightmare. If police are confident that they are using this technology in a straight and narrow sort of way, then they should release their usage logs so researchers have a better pile of data to sift through and be able to comment. But seeing the numbers in these logs, and knowing that out of 23 responses to 80 total requests, only two had usage logs included, raises a lot of questions.

Both logs are embedded below, or can be read on their request pages.

Image via Cellebrite