For nearly sixty years, the CIA has resisted the Government Accountability Office’s (GAO) efforts to perform a full audit of the Agency, even going so far as to not only render themselves exempt, but to spread this exemption throughout the rest of the Intelligence Community. When the GAO got fed up and quit, the CIA tried to have the letters detailing their frustrations classified.

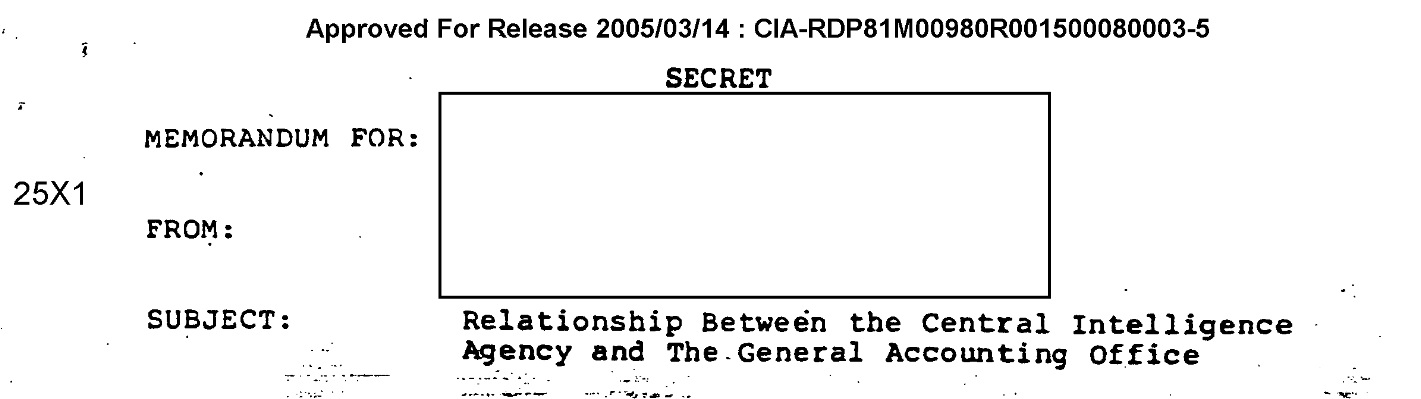

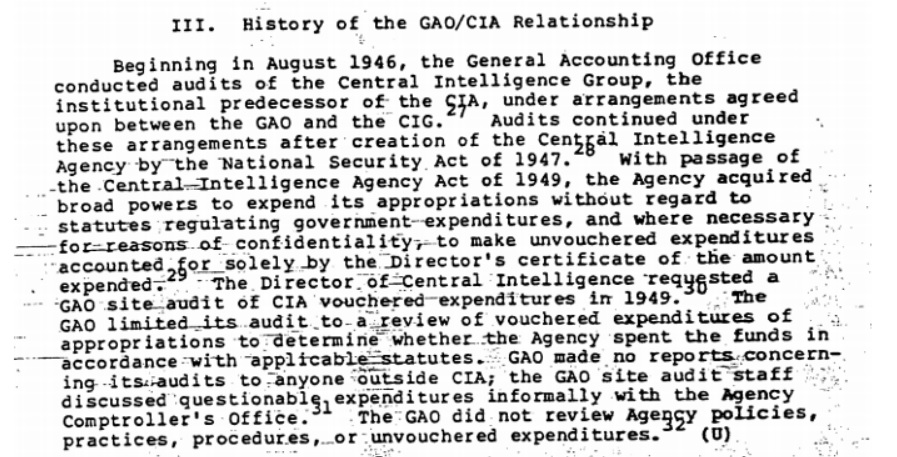

CIA’s history with the GAO slightly predates the Agency’s creation, as the GAO’s first relevant audit was conducted in 1946 with the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), CIA’s direct predecessor. In 1947, the passage of the National Security Act created the Central Intelligence Agency, at which point GAO continued the audits with CIA under similar arrangements as with the CIG. However, the passage of the Central Intelligence Agency Act of 1949 would serve as the beginning of the conflict between CIA and the GAO. The CIA Act empowered the Agency to make unvouchered expenses “without regard to statutes regulating government expenditures.” The details of these expenses were known only to the Director of Central Intelligence, authorized them at their discretion, and anyone the Director decided had a need to know.

Such a policy is obviously useful to an intelligence agency engaged in clandestine activities, but it also makes oversight a difficult proposition. Declaring such an audit off-limits, Director Hillenkoetter requested the GAO conduct a limited audit of the Agency’s vouchered expenses “to determine whether the Agency spent the funds in accordance with applicable statutes.” However, the GAO’s reports weren’t made available outside the Agency, expenditures were discussed with the Agency only informally and the GAO didn’t review any Agency policies, practices, procedures or unvouchered expenditures.

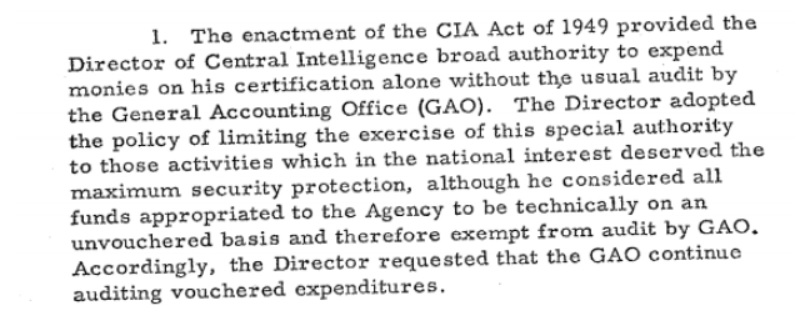

The Director’s decision to ask the GAO to perform a limited audit is interesting, as other declassified CIA papers show that he considered the Agency to be completely exempt from GAO audits beginning in 1949.

The explanation for CIA’s cooperation appears in another, later document produced by the accounting firm Touche-Ross, which was under contract with CIA. (It’s unclear if Touche-Ross is the “proprietary” CPA firm CIA said they were using for audits.)

According to the Touche-Ross report, “early Agency management [wanted] to establish with the Congress a baseline of confidence in the integrity of the fiscal operation of the Agency. … Therefore, they insisted on financial audits … in the belief that such audits would … be a convincing item to point to in Congressional hearings.” In other words, CIA claimed total exemption from the GAO’s audits but insisted on partial audits by GAO in order to earn brownie points with Congress.

GAO fundamentally disagreed with CIA’s opinion, stating that there was no exemption from their audits for “intelligence sources and methods.” Nevertheless, GAO was uniquely powerless to compel CIA to cooperate.

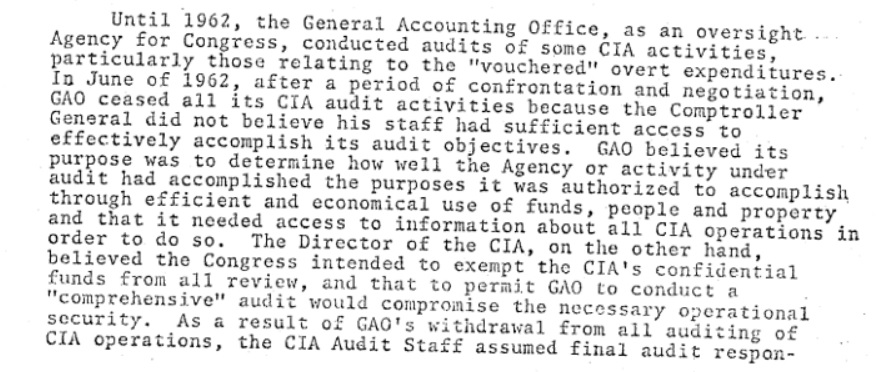

As a result of the Accounting and Auditing Act of 1950, the GAO expanded its audits of agencies to include determinations of whether they used their personnel, property and funds “in an efficient, economical and effective manner.” Throughout the 1950s, however, the GAO continued its highly limited audits of CIA under Directors Smith and Dulles, a process which the Agency tolerated due to their ability to define the scope of the audit and inquiry. This changed in 1959 when the GAO decided they could apply their “broader comprehensive audit” to CIA. The details of what happened next remain partially classified, but a narrative does emerge from the documents - one more complex than what’s presented in CIA’s summary.

Despite the Agency’s claim that their internal fiscal and management controls were strengthened simultaneously with the GAO’s discontinuation of audits of CIA, it would be more than ten more years before any of the Agency’s audits specifically looked at program effectiveness and other aspects that GAO had sought to address. Later reports would attempt to justify the exemption of unvouchered funds from GAO audits as being necessary to protect necessary operational security. While there is some truth to this, other documents show that the CIA’s practices effectively prevented the GAO from conducting an adequate audit of even its overt activities.

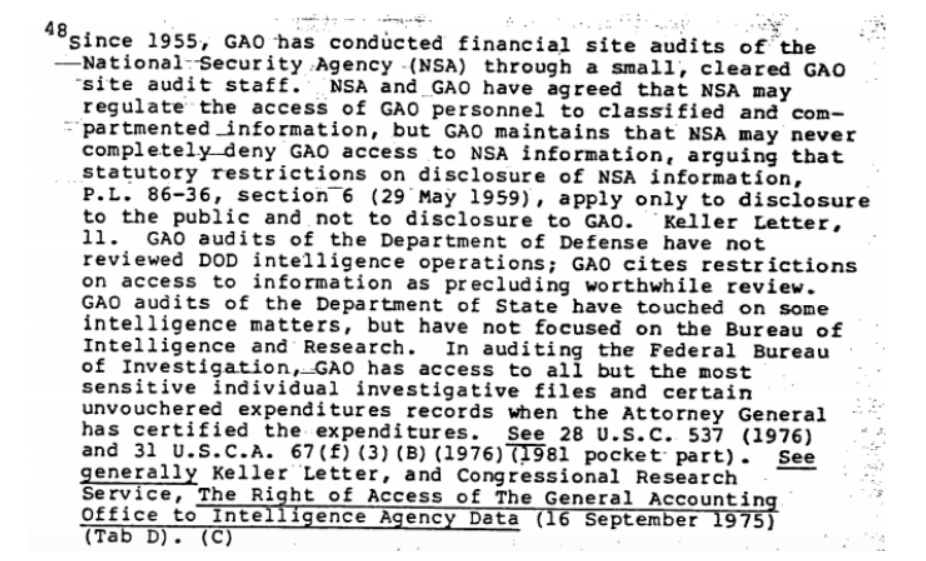

CIA’s claim that the need for secrecy prevented a proper GAO audit is also undermined by the Agency’s confession that beginning in 1955, the GAO had reached an agreement with NSA to perform audits of their agency. At the time, NSA was jokingly said to stand for “No Such Agency” due to the extreme level of secrecy around it.

Nevertheless, GAO’s subsequent reviews of CIA were few and far between, and only at the direct request of Congress.

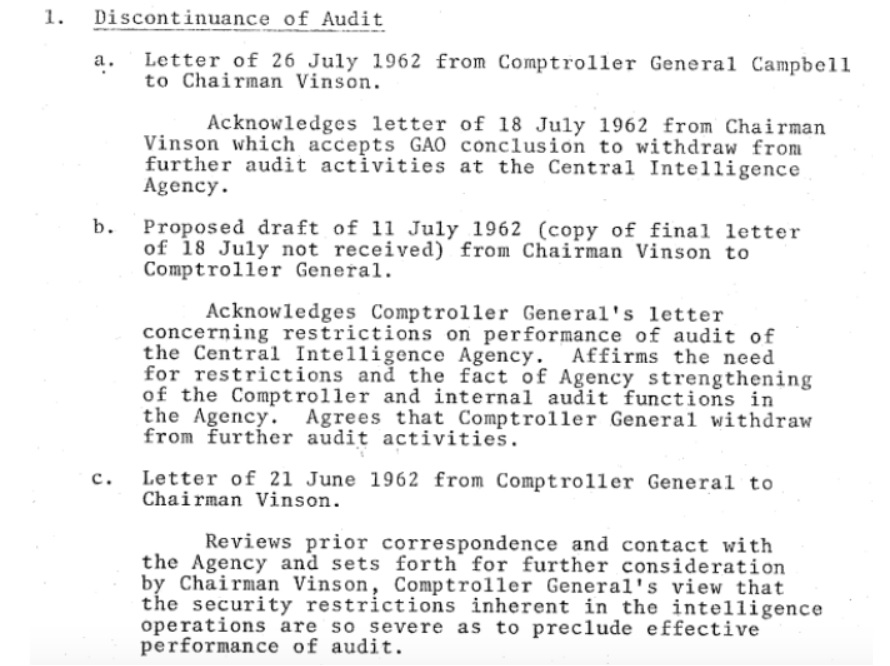

The date in the excerpt above, July of 1962, is a crucial time period for understanding GAO’s relationship with CIA. Unfortunately, many of the papers discussing this time period and CIA’s obstruction of GAO audits remain classified as “intelligence methods.” Nevertheless, summaries of some of the key correspondence have been declassified by CIA.

While the GAO audits were officially discontinued in 1962, the GAO had concluded a year before that the effort was a waste of time due to CIA’s restrictions.

CIA’s documents show that the effort would have been abandoned then, but was continued due to “the political climate then prevailing in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs affair.” It was only after the political pressure had died down that CIA decided to accept GAO’s decision to finally discontinue the audits.

Read Part 2 here

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Wikimedia Commons