While getting the cold shoulder from the FBI might had ended the CIA’s formal involvement in the Alaskan Stay-Behind plan, declassified documents show that several years later the Agency was looking at the Cold War contingency as a learning opportunity - particular in regards to burying weapons caches.

According to an April 1955 memo, an individual with a redacted identity visited someone known only as Identity A on the 19th of that month. Presently, all that’s known about Identity A is that they were “charged with caching activities within the Territory of Alaska and the Aleutian Chain.” In their meeting, they discussed how efforts to cache supplies had gone so far, and the various problems that emerged - caches buried under ground tended to be a lot of trouble to bury, monitor, and ultimately retrieve, especially with melting permafrost six feet under.

As a result, Identity A was switching their efforts to above ground caches “utilizing buildings of log construction.”

The memo, which was written either by or for the Chief of CIA’s Soviet-Russia division, concludes by noting that “arrangements will be made for supporting the caching teams and obtaining sites for the activity.”

Several months later, the Chief of CIA’s Soviet-Russia division was coordinating with the Assistant Chief of the Technical Services Staff to study the efforts of the joint FBI-military Stay Behind network. Specifically, any lessons learned about the containers and methods of preservation were seen as useful, and would aid in CIA tests at Fort Churchill in Canada. The language suggests that the Agency was less confident about caching crucial materials in abandoned buildings above ground, a notion that was confirmed by an October 1955 memo to CIA’s TSS Chief.

According to the memo, CIA was concerned about their ability to quickly locate underground caches, having previously tried using probes and Geiger counters, and finding them inadequate to the task. The hope was that TSS could construct an “Invisible Light Cache Locator” using infrared, which would have allowed caches to be quickly found and recovered at night.

By the end of that month, it seemed that just such a system was being used. Unfortunately, the infrared system also made it possible to locate the caches without using infrared. For the system to work, a tall metal pole with an infrared reflector had to be erected over caches, allowing anyone with an “infra red flash gun” to relocate the cache. However, the pole could be spotted without such a device from either the air or the ground.

While CIA was looking at the Air Force’s program as an experiment, it was very much a live exercise for the Air Force. As a result, the Agency expected “little help from the Air Force R&D-wise.” The memo also clarified that storing caches in log cabins above ground only worked in wooded areas. It also revealed that the biggest threat to these caches wasn’t inquisitive people so much as it was inquisitive bears - oddly, a padlock was seen as sufficient against these bears despite noting that they “can go thru heavy barriers” when hungry.

Memos over the next several months reveal that unlike the examples listed by the Air Force, CIA wasn’t interested in simply storing food, survival supplies and other tools - they wanted to store weapons.

According to a formerly SECRET document, CIA believed it was important to cache materials and weapon “during the period of cold war or peace.” These weapons would then be retrieved by Stay Behind forces to perform acts of sabotage or a coup de main/surprise attacks.

Included in the Agency’s list of “essential items” to cache were a number of items, ranging from “standards” such as explosives, incendiaries, and limpet kits, to less standard ones, such as radios or medical and photographic kits. Personal arms such as handguns and disassembled submachine guns could be stored in the cache containers, while other weapons sought by the Clandestine Services couldn’t yet be safely stored.

These items they wanted to store but were unable to included submachine guns, light machine guns, mortars, rifles, sniper rifles, automatic rifles, recoilless rifles, and shoulder mounted rocket launchers. To support these weapons, CIA wanted both individual containers, and containers that could fit multiple weapons. At this point, none of their efforts, including “wrapping, cold dipping, sealing, boxing and crating”, had proven up to the task.

As the caching program continued the next year, CIA performed a number of experimental tests. In the remarks section of one of the memos discussing these experiments, the Agency makes several odd and almost disturbing remarks. First is that “the local black market” will make procurement easy and that U.S. Army materials can be bought on it. Second is the note that, in rural areas, graveyards and burial plots make excellent caching locations. The latter is an old but distasteful tactic of military and paramilitary cachers, as graves are both easily found and rarely disturbed.

While there’s no doubt that these tests were part of the same effort to create caches of supplies for stay-behind assets, it’s unclear how directly related these tests were to the Alaskan program. However, there’s no doubt that CIA was learning from the Alaskan efforts of both the FBI and the Air Force.

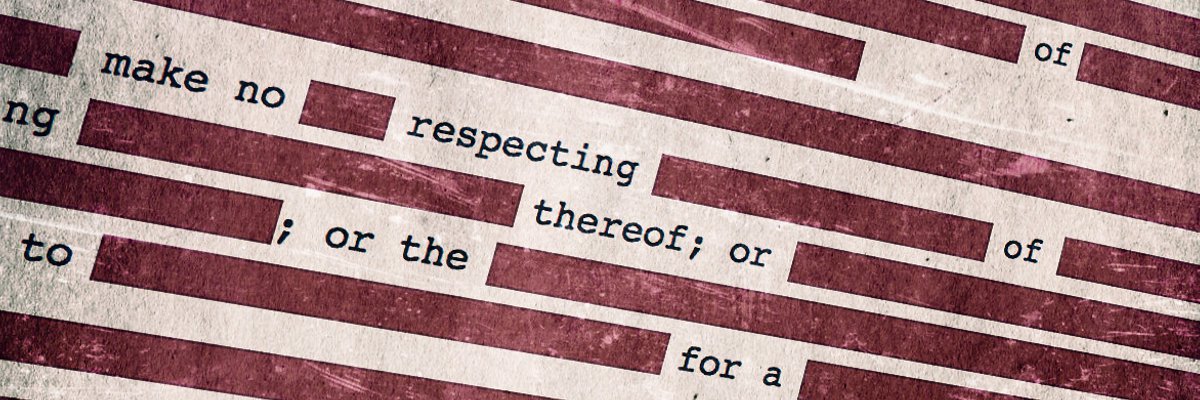

Photos of actual weapons caches left by the CIA are embedded below.

Like M Best’s work? Support them on Patreon.

Image via ForgottenWeapons.com