To accomplish its mission, the Central Intelligence Agency will undertake missions utilizing assets, agents, and officers under official and nonofficial covers. When these missions require the use of an organization, the Agency will resort to the use of proprietary companies and organizations as a means of maintaining cover or accomplishing goals that the U.S. Government isn’t able to openly support. Eventually, the Agency has to terminate these proprietaries. The story of how that happens is where things get interesting.

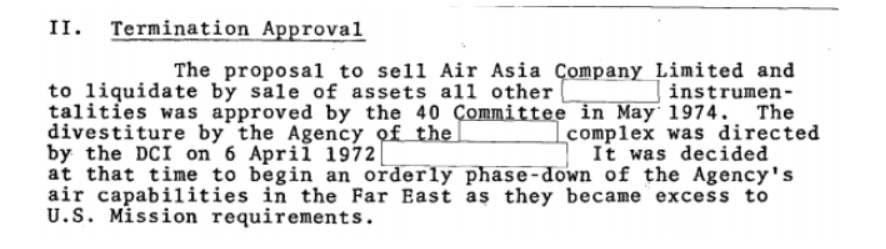

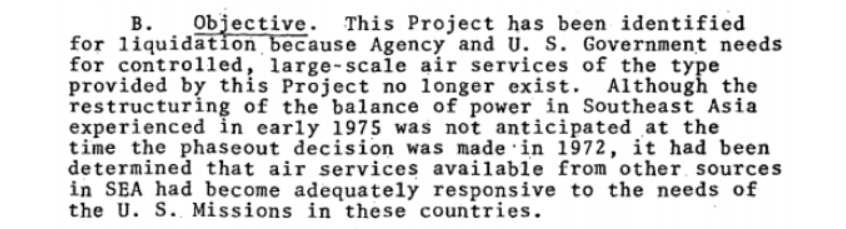

In the instances where the Agency voluntarily dissolves a proprietary without reassigning its resources, it is simply because they determined it’s no longer needed. Even in these instances, however, the proprietary’s associated activities are unlikely to end altogether. In the example of Air America, Air Asia, Civil Air Transport et al, the Agency decided that their capabilities exceeded “U.S. Mission requirements” and so their air capabilities began “an orderly phase-down.”

Even in this instance, however, it did not mean that their activities ended. Rather than replace it with a new proprietary, even in the light of the 1975 rebalance of power in Southeast Asia, the Agency turned to “air services available from other sources in [Southeast Asia]”. While the exact language leaves open the possibility that these other services were new Agency proprietaries, the context suggests that they were independent service providers that would be available on a contract basis. Certainly, using a legitimate, preexisting group would make it easier for the CIA to maintain deniability and draw less attention than the creation of a new airline to begin regional operations.

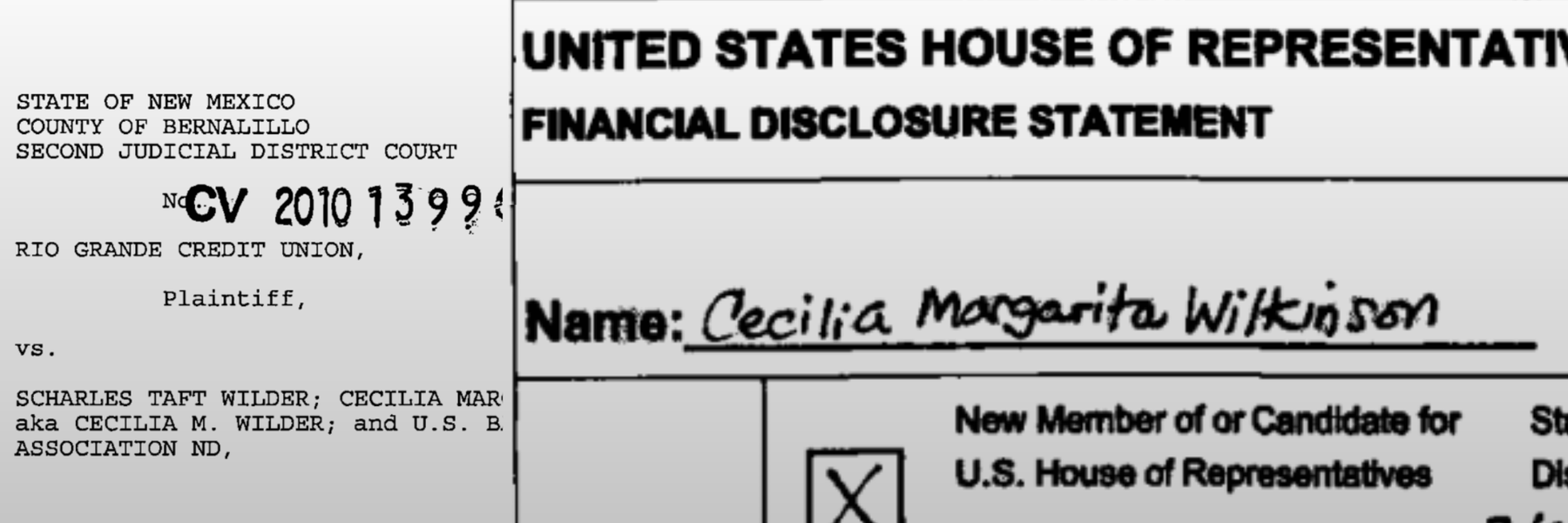

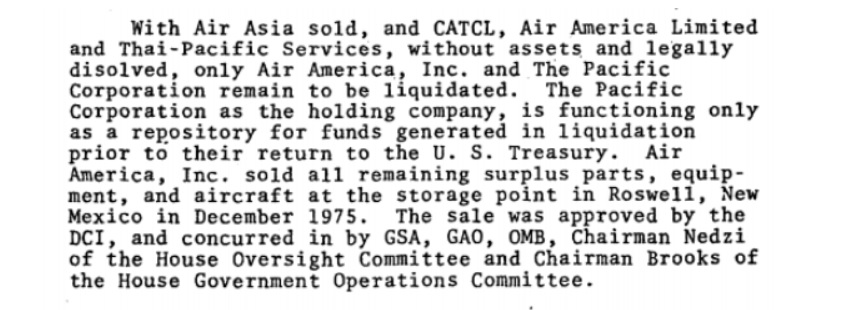

With no need to keep the resources for the airline proprietaries, their physical assets were sold off and the funds transferred to The Pacific Corporation for holding “prior to their return to the U.S. Treasury.” The sale of the assets were coordinated and approved by the DCI, the GSA, GAO, OMB, as well as the chairmen of two Congressional committees. The companies’ liquidation would be audited by the CPA firm Coopers and Lybrand following the final transfer of funds back to the U.S. Treasury.

In many other instances, however, the dissolution of a proprietary simply meant a new project (or a new way of funding it) would be created to accomplish the same goals. A declassified CIA memo from 1967 shows the Agency discussing how it would handle the termination of certain projects as a result of the new restrictions imposed as a result of the Katzenbach report. For The Asia Foundation, this meant finding it another way of providing it with government funding rather than actually terminating the foundation itself. Documents show that this was far from an aberration.

In 1967, the Katzenbach Committee’s report forced the CIA to end their relationship with a number of covertly funded and controlled groups. In several of these instances, the Agency planned to create new projects to replace the old ones. CIA’s Executive Director-Comptroller, L.K. White, wrote that “even in those areas where it has been decided that CIA will drop certain projects completely … [the Agency will require funds for] new projects which might be generated to accomplish the same objectives in a manner not in conflict with the Katzenbach report.” For its part, Congress appeared fine with this so long as CIA was “rather specific” when justifying retaining the funding. In the instance of The Asia Foundation, the Agency wound up borrowing money from itself in order to provide the foundation with more than a year’s worth of funding in a “surge” to keep it going until other government funds could be arranged.

In a memo written a month later, the Executive-Director Comptroller wrote that the Agency wanted the full funding for all groups reviewed by the Katzenbach Committee, and which the Agency was supposed to end its relationship with. He doubted that the request would be treated favorably, and reiterated that they would need to provide very specific reasons and rationale why.

The reasons for the surge funding likely varied, though many of the examples apparently remain classified. In some instances, like The Asia Foundation, it was to keep the organization going without direct CIA sponsorship. In other instances, the funds were simply to keep the group going through the liquidation process. Even in those instances, however, at least some of the groups, e.g.The Asia Foundation, already had liquidation funds in place. These funds were to be used in the event that the group suddenly lost its CIA support, and were calculated to be enough to help them minimally wind down operations, such as by helping personnel return from oversea.

Despite the existence of the Liquidation Plans, the Agency was confronted with a new problem about how to actually wind down these projects. As one memo from 1967 noted, “there is no stereotyped procedural precedent, [so] documentation must be developed appropriate to each case.” This documentation would address the process of handling the surge funding et al. While the Liquidation Plans and funds in place may have provided the equivalent of an emergency parachute, the Agency was understandably looking for a more orderly wind-down.

It was proposed that a short-term task force be created to address these issues.

The memo concluded by stating that “the overlying principle is that we are not engaged in a lump-sum give-away of the funds authorized.” Rather, it was “in the protection of government interest” to fulfill various agreements “and to define the moral, and as practical, the legal liability of the recipients.” If there were problems with these terms, “there is to be an Agency option to shut off the forward flow of funds, in the event of failure to conform with the spirit and intent of the terms of reference.” This seems to have been a reasonable measure, despite the ridiculous sounding fact that the CIA was retaining the right to cut off funds they were providing groups in order to fund the cutting off of CIA funds.

The next day, the proposal was approved by the Agency’s Deputy Director for Support, its General Counsel and the Acting Deputy Director for Plans.

In some instances, liquidating the proprietaries is fairly straightforward, as it was with Air America et al. In other instances like The Asia Foundation or Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, the process is complicated by the fact that the organization isn’t actually being liquidated. The complex RFE/RL liquidation process will be examined in the future, in the meantime you can read the Agency’s liquidation plan embedded below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image by D Guisinger via Flickr and licensed under Creative Commons BY 2.0.