Five years after closing the Marion Adjustment Center and extracting itself from any relationship with private prisons, the State of Kentucky is planning to reopen CoreCivic’s Lee Adjustment Center in Beattyville, reversing course and and highlighting two common, core reasons for the short-lived position: a bloated state prison system and the economic desperation of the town in which the facility is reopening.

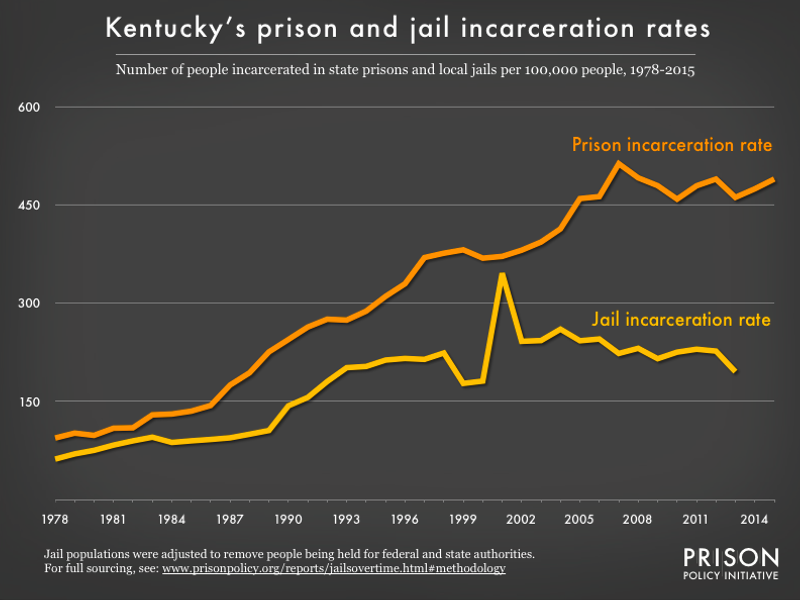

According to the Department of Corrections, opioid addiction has added strain to an already overcrowded state system. Kentucky currently has the seventh highest incarceration rate in the country; the majority of its facilities are overpopulated, some at as much as 200 percent of the recommended capacity. And the eastern Kentucky town of just under 2,000 people where Lee Adjustment Center has sat since then-Corrections Corporation of America, now-CoreCivic built it in 1998 has been dubbed the poorest white town in America, a depressed rural American area, like so many others, where few employment opportunities take root and the average median income per household is less than $15,000 per year.

The day-to-day need for regular jobs is a not-uncommon added draw of private prisons.

In addition to the Marion and Lee Correctional Centers, Kentucky is also home to the Otter Creek Correction Center.

That facility has also been unused, since a 2012 series of sexual misconduct allegations against male correctional officers came to light.

CoreCivic has been the recipient of numerous allegations of fraud, abuse, unsanitary conditions, and illegal practices, which were, in part, cause for a brief moment in the latter half of 2016 when the federal Department of Justice refrained from their use.

However, since the election of President Donald J. Trump, the private prison industry has been optimistic about its survival in an immigrant-cautious, law-and-order environment.

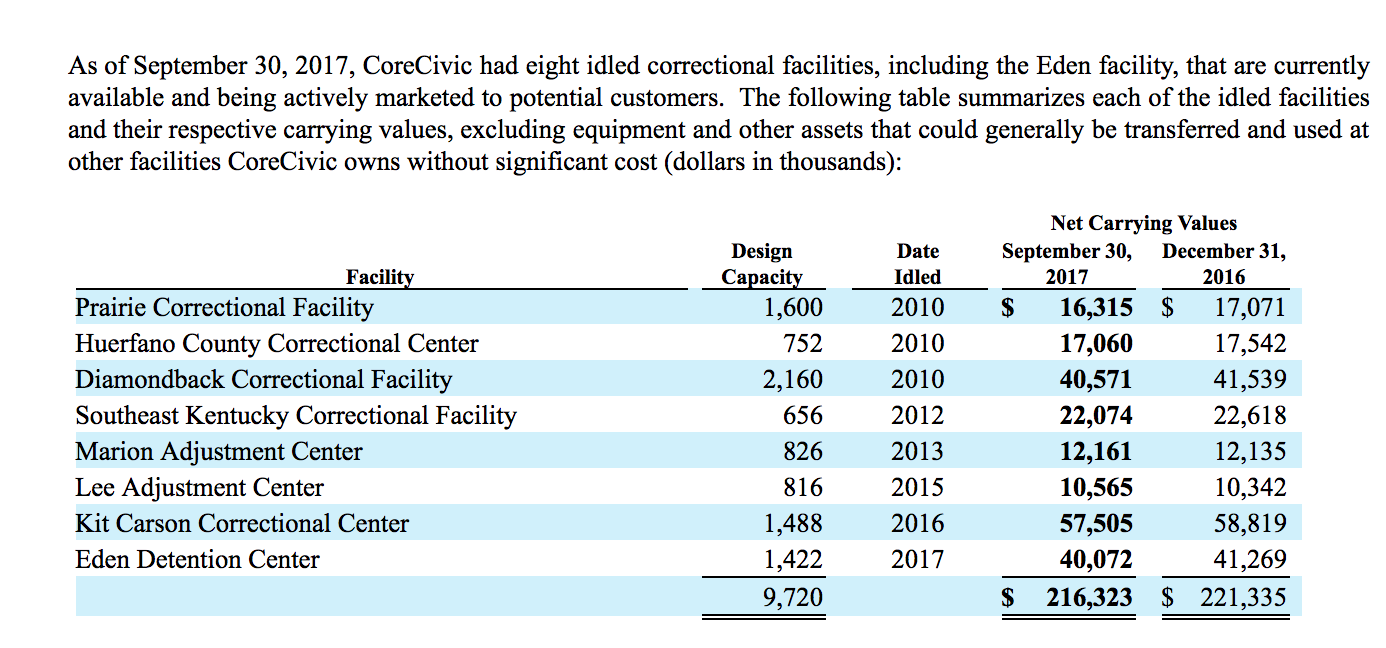

CoreCivic’s most recent filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission still list Lee as one of its eight current idle facilities, prisons which have been built and maintained but currently do not have any inmates or government relationships. The company “evaluates on a quarterly basis market developments for the potential utilization of each of these facilities” and has “determined each … to have recoverable values in excess of the corresponding carrying values,” meaning that even as one private facility closes, there is a party actively lobbying for its reinstitution. The economic circumstances of these prison locales frequently encourage local officials to become part of that chorus.

MuckRock is awaiting the most recent copy of Kentucky’s renewed agreement with CoreCivic. You can follow that request via the request page or explore the past agreements via the links on the sidebar.

Do you have some private prison information we should know? Help us out by leaving your tip in the form below.

Image by Stephen Melkisethian via Flickr