The SIGNA Society, whose name means “written seal” and whose motto translates as “To have Served is the Greatest Virtue,” is the Central Intelligence Agency’s barely acknowledged secret society of retired Agency security officers.

Not to be confused with CIRA, the other group of CIA retirees (whose website is restricted), the SIGNA Society predates CIRA by about five years. Its members are also, according to CIA files, not entirely retired. While SIGNA’s charter states that it “has no relationship whatsoever with its former employer,” memos from CIA’s leadership state that SIGNA’s “members support the Agency in various ways, sometimes compensated, sometimes not.” SIGNA’s members have been known to “contribute significantly as ‘on-call’ investigators,” by assisting with the Agency’s covert activities, with recruiting and with “spreading the word” through corporations and other parts of the U.S. Government.

To the public, the SIGNA Society barely exists. Its LinkedIn page lists only a P.O. Box and no actual information about the group. The public pages on its official website only say that it’s “for a select group of federal retirees.” In a stunning lack of OPSEC failure, however, they do list the date, time, and location of their next social and business meeting. Beyond this, there is barely any information about the group outside of its and CIA’s files. A meager handful of obituaries mention the SIGNA Society, while the group’s non-profit information simply shows that its Treasurer is (or very recently was) Jack Bowden, a 23-year veteran of the Agency, where he served as a security manager in the Office of Security, while another listing shows Patrick McMahon as the point of contact for the group.

For even the slightest glimpse at the organization’s history and activities, we must turn to CIA’s files.

Although the SIGNA Society was first formed in April 1970, its nonprofit status doesn’t appear to have been recognized by the IRS until September 2014. According to a 1981 memo to the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence (DDCI), the group’s charter indicated that it was “a nonprofit, nonpolitical organization founded by retired Agency employees, does not promote or sponsor any causes, and has no relationship whatsoever with its former employer.” This technicality about the charter’s wording didn’t stop CIA’s Director of Security (DOS) stating, immediately after citing the charter, that “SIGNA is very supportive of the Agency.” This apparently applied to the entirety of the group on an individual level as well, as the DOS states that they “all tenaciously defend the organization in both private and public occasions.” The DOS even suggested the DDCI meet with SIGNA and explain “the ways which Agency retirees might properly and correctly help the Agency without generating unfair criticism from the news media.”

In addition to the DDCI addressing the SIGNA Society at that year’s annual convention, the group would also be hearing from John McMahon (not to be confused with Patrick McMahon, mentioned above). Due to his extensive career with the Agency, McMahon was seen as being in “a unique position” to discuss the “technical, operational, and analytical programs” as they related to the Office of Security.

CIA’s archives indicate that it wasn’t unusual for the SIGNA Society to meet with senior level Agency personnel. Memos indicate that several years before, they would have met with George H.W. Bush, the then-CIA Director, if he hadn’t been out of town. Instead, they met with the DDCI. This trip was being coordinated in part by Robert Gambino, the DOS for the Agency at the time. Several years later, he would serve as the president for the SIGNA Society.

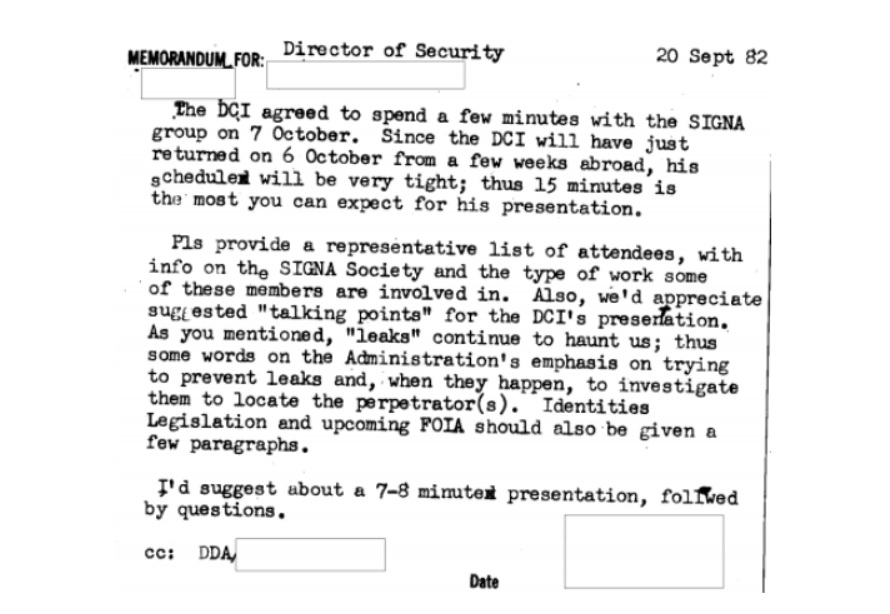

By 1982, the SIGNA Society had over 250 members, many of whom would be attending the annual convention. This year, the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) was to make a personal appearance. In an initial briefing memo suggesting topics of discussion, Gambino’s replacement as the Agency’s DOS noted once again that the group was “nonprofit and nonpolitical” according to its charter, yet was “most supportive of the Agency and assiduously defends it.”

A memo written just two weeks later, also from the DOS, goes further in describing the Agency’s relationship with the SIGNA Society. While some of SIGNA’s members may have been fully retired, others were “actively engaged in work, usually related to security.” More than that, “some SIGNA members are still associated with the Agency in contract status and contribute significantly as “on-call” investigators and in other security specialties.”

It’s notable that the mention of SIGNA members being associated with the Agency is included with general, non-trivial information about the group. While it may not have been part of SIGNA’s charter, the DOS felt it was important for understanding the group’s relationship with the Agency beyond defending it and advocating for it. It’s also notable that the DOS had been planning this section of the memo for over a week.

In a response to an unsigned request, likely from the DCI’s office, the DOS produced a list of talking points for the DCI. Due to the limited amount of time the DCI would be able to spend with the SIGNA Society, it was recommended that the talks focus on the problem of disclosure, with a primary focus on leaks. The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) was also to be discussed, an unsurprising fact since the Agency had, the year before, begun to include FOIA in its war on leaks.

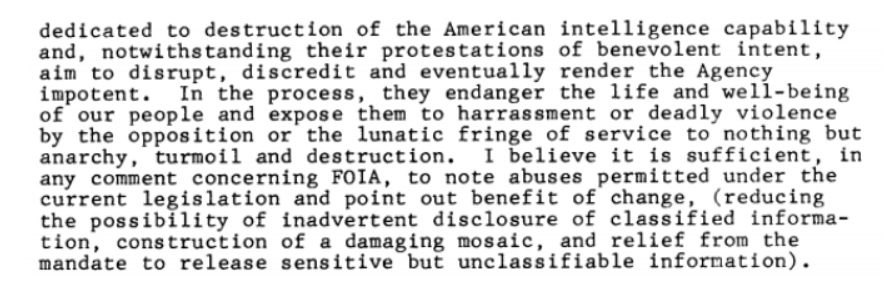

The DOS recommended that “any topics other than leaks be afforded very brief treatment.” The leaking or revealing of the identities of covert personnel could be presented as an especially dangerous act, which is often truly the case. When it came to FOIA, however, it was suggested that the DCI “note abuses permitted under the current legislation” and advocate for a change in the FOIA legislation. The Agency felt they were being forced “to release sensitive but unclassified information” and that they risked “the construction of a damaging mosaic.” The Agency’s mosaic argument, for those not familiar, essentially stated that they could release either Information A or Information B, but they shouldn’t be compelled to release both A and B. The legislation should also change, the Agency argued, because they couldn’t be trusted to properly review documents and prevent the “inadvertent disclosure of classified information.”

Like all of the briefings by active CIA personnel to the SIGNA Society, the DCI’s was to be unclassified. How unclassified? See for yourself.

Read Part 2 here

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.