When Mexican spymaster Miguel Nazar Haro was implicated in a car theft ring operating in both the United States and Mexico, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) moved to prevent prosecution of one of their most valuable assets. As the investigation revealed, however, the web of corruption surrounding Nazar, the head of Directorate of Federal Security (DFS), connected to more than just grand theft auto, with ties to narcotics trafficking, the torture and disappearance of numerous dissidents, and at the murder of DEA Agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena Salazar.

When a U.S. Attorney wanted to prosecute Nazar for his role in the car theft ring, the CIA intervened to protect their asset. As a result of the prosecutor revealing the CIA’s obstruction, he was fired by President Reagan.

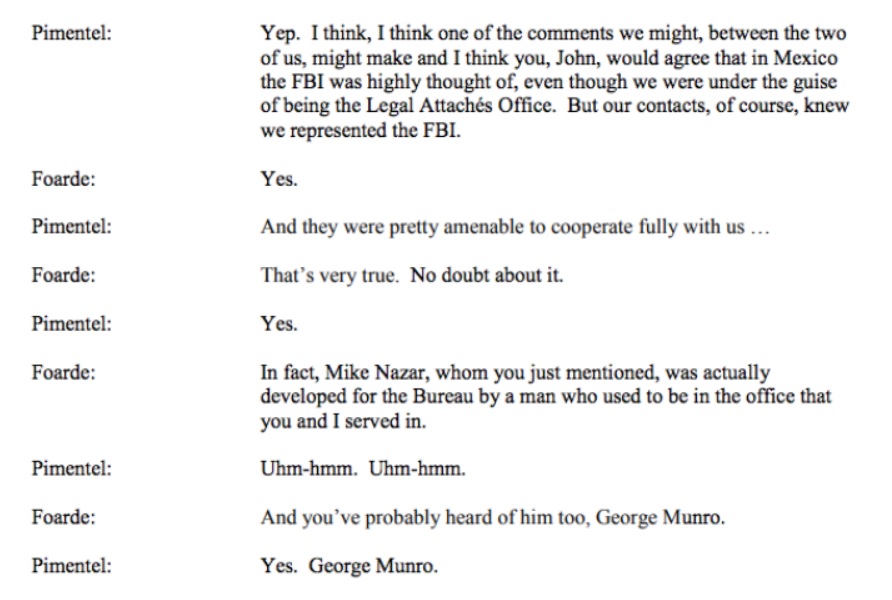

As it would turn out, the Agency had shared Nazar with the FBI. Former FBI Special Agent John Foarde stated that Nazar and Mexico were both “pretty amenable to cooperate fully” with the Bureau. He also traced Nazar’s relationship with the Bureau back to George Munro, who had worked for the FBI in Mexico before joining the Agency and who had been responsible for their surveillance of the Soviet embassy in Mexico City. According to Foarde, Nazar “was actually developed for the Bureau” by Munro. This not only re-confirms Nazar’s pre-existing relationship with both the CIA and FBI, it links Nazar’s work with the Bureau to the Agency.

Before Nazar’s death, he was interviewed by Jefferson Morley and Michael Scott for the book Our Man In Mexico. In the interview, not only did Nazar no longer deny his relationship with the CIA, he described “his close working relationship and friendship with the [CIA’s Mexico City station chief] between 1960 and 1971.” As a result of his role in Mexico’s police and intelligence forces, he was in a prime position to provide the U.S. Government with information - or not to. When the House Select Committee on Assassinations interviewed Nazar about Lee Harvey Oswald’s mysterious time in Mexico City, he appears to have waved them off and encouraged them to focus their investigation on the time after Oswald had been arrested. This is especially significant in that it was a report by Nazar that provided the CIA with some of their intelligence on Oswald’s activities and contacts in Mexico City.

Perhaps far too unsurprisingly, the released FBI file on Nazar barely acknowledges his involvement in drug trafficking or his ties to the CIA. While this might be expected due to the connections to the CIA and Nazar’s own role as an intelligence officer, the FBI failed to include either their standard GLOMAR for such individuals or a citation of FOIA exemption b(1) (classified information) with the FOIA releases on Nazar. Exemption b(3) was cited only in regards to the rules of federal procedure and grand jury information. If we take the FBI’s response and lack of cited-exemptions at face value, it means that the Bureau was aware of, but chose to ignore connections between a high profile CIA asset/FBI liaison and major trafficking operations that involved stealing cars into Mexico. No mention is made in the released file of Munro or of Nazar’s cooperation with the Bureau.

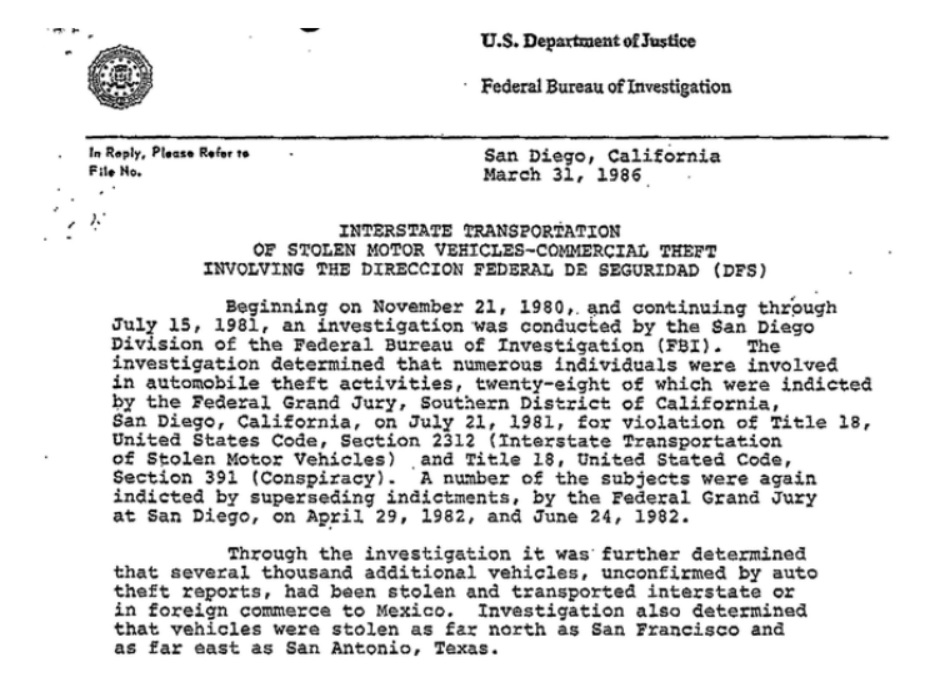

Nazar’s role in the Mexican police and intelligence establishments, as well as his long history of cooperating with the CIA, gave him considerable protection from prosecution. With vehicles being stolen in the United States and transferred into Mexico, prosecution became even less likely and investigation far more difficult. Nazar enjoyed this virtual immunity until November 1980, when the FBI opened an investigation into a car theft and trafficking ring. The investigation ultimately determined that “several thousand” vehicles were stolen and transported into Mexico. The ring’s reach was considerable, extending up to San Francisco, 500 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border. Given that its reach extended as far east as San Antonio, the car theft ring appears to have operated in up to 850,000 square miles of territory within the United States.

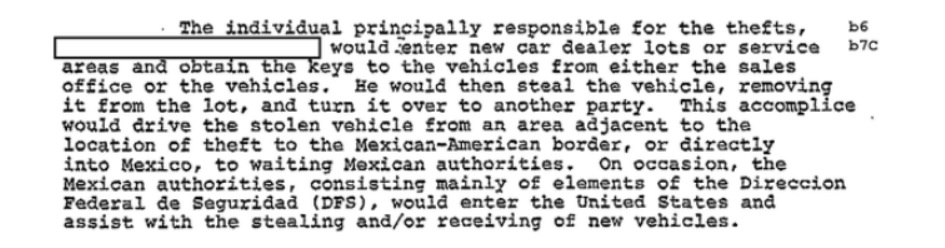

The ring’s tactics will be familiar to investigators with experience in high end car theft: rather than steal cars off the street, the ring’s thieves would visit dealerships and service stations. From there, they would take the keys, either stealing them or taking them with permission for a supposed test drive, and deliver the vehicle to another person who would then deliver the stolen car either into Mexico or directly to Mexican authorities. According to the FBI’s file, it wasn’t unheard for the Mexican authorities, “consisting mainly of elements from the Direccion Federal de Seguridad” (which Nazar led) to come into the United States to help with the theft or delivery of the cars.

According to the 1986 FBI document, at least one of the stolen vehicles was delivered personally to Nazar. This information would later be corroborated by news outlets.

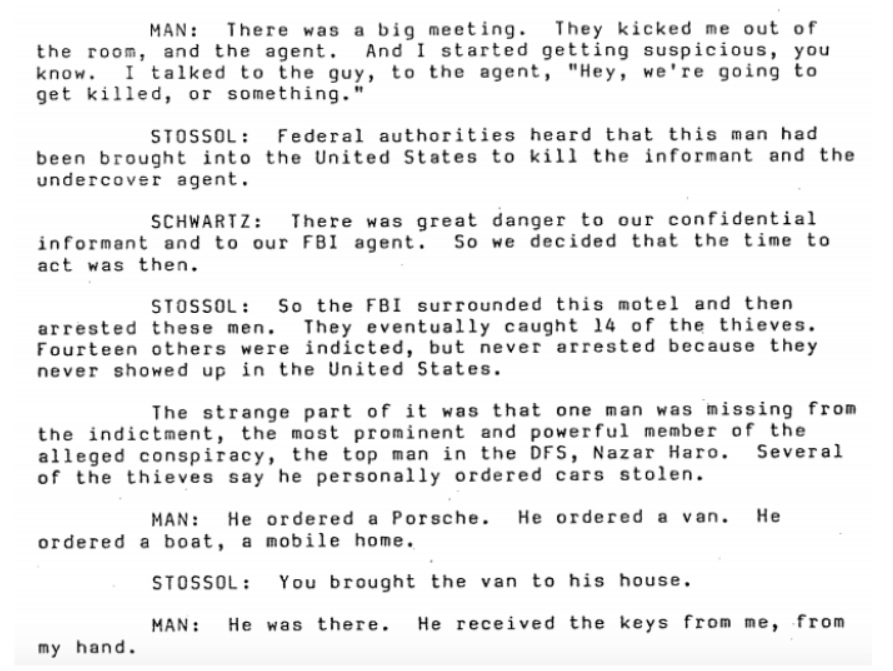

As John Stossol noted on 20/20, the thieves targeted high end cars, with Stossol expressing the view that the high value of the cars made the crimes worse. He did, however, appear to concede that the theft of “a few motor homes” was also unfortunate.

A page from the FBI file, written in 1987, expanded on some of the details of the thieves’ modus operandi:

Eventually, Nazar was indicted, along with twelve other individuals from the DFS, for his role in the car theft ring.

While heavily redacted, the FBI file reveals that part of what led them to Nazar’s involvement in the ring was an informant who had personally delivered a stolen van to Nazar.

The 20/20 segment archived by the CIA provides some additional details. Along with the Assistant U.S. Attorney in San Diego, 20/20 explains that Nazar didn’t start the car theft ring - he seized control of it from Gilberto Peraza Mayan.

As a pseudonymous Mexican intelligence officer told 20/20, “The [DFS] has unlimited powers. They can arrest a person and put you in prison there as a political prisoner for life, as long as they want. They don’t have to answer to anyone.” Nazar and DFS acted with impunity in Mexico.

While it was impossible to catch and punish Nazar’s ring in Mexico, they weren’t quite as immune in the U.S. In November of 1980, California’s Highway Patrol stopped two cars stolen by the ring on their way into Mexico, with one of the thieves becoming a Bureau informant. With the help of the informant, the FBI was able to film the car theft ring as they met in a San Diego apartment. At this meeting, one of the DFS agents bragged about their “ability to bring cars and guns into Mexico.”

For eight months, the FBI ran an undercover operation against the ring as hundreds of cars continued to disappear into Mexico. When the car theft ring started smuggling automatic weapons into Mexico as well, the Bureau decided it was time to move.

But when the indictment came down, partially as a result of an assassin apparently having been dispatched to the United States to eliminate the Bureau’s undercover agent, Nazar’s name was conspicuously missing despite the clear evidence against him.

20/20 learned that Nazar had been protected by the U.S. Government, with an FBI cable reportedly saying that damaging Nazar’s interests would damage U.S. national security interests.

According to multiple individuals, including unidentified intelligence personnel and two named members of the U.S. Attorney’s Office, the Agency considered Nazar to be “indispensable” and their “most important source in Mexico and Central America.” Prosecution would endanger that by depriving Nazar of his position of authority. “If we lost him”, DOJ officials were told, “it would be a disaster.” In response to the obstruction, U.S. Attorney William Kennedy went public with the San Diego Union.

As a result of this exposure, Kennedy was pressured to resign. When he refused, and the Department of Justice (DOJ) ultimately decided not to fire him, President Reagan fired him for exposing one of CIA’s sources. According to one report, senior officials at the DOJ had recommended his firing to President Reagan. The reason behind DOJ’s apparent change in position isn’t immediately clear, though it seems extremely unlikely that under the circumstances senior DOJ personnel would have made such a recommendation without at least the indirect support of CIA. According to the Attorney General at the time, Kennedy’s “comments were highly prejudicial to the interests of the United States.” After all, according to the New York Times, “the Federal Security Directorate gathered information used by the Reagan administration to justify assertions of Soviet and Cuban subversion in the region.”

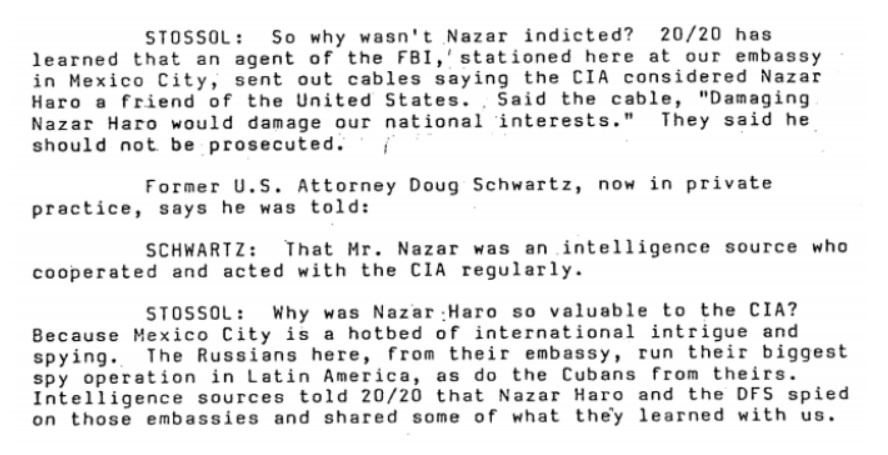

The exposure is one of several factors believed to have contributed to the temporary end of Nazar’s career with law enforcement and intelligence. As a result of Nazar’s cover being blown, the CIA ultimately withdrew their objections to prosecution - most of the damage was already done. Nazar, however, still believed he was untouchable. In response to a TIME article that referred to his criminal activities, Nazar decided to come to the United States to file an $11 million lawsuit against the outlet. The FBI used the opportunity to arrest him on February 23rd, 1982.

Bail was set at $1,000,000 with a $200,000 bond, which was promptly paid in cash by an unidentified party.

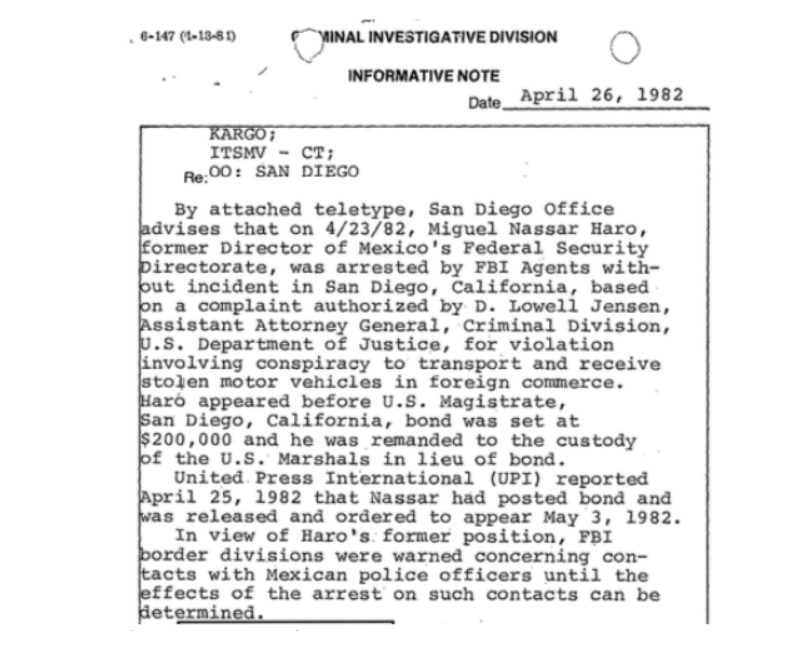

For its part, the Agency disagreed with the negative press surrounding Nazar, and found at least some of it lacking in objectivity “from the Agency’s point of view” according to a memo sent to the CIA Director. The Agency did not explain in any of their declassified documents what they considered the facts to be or what they thought objective reporting would have looked like. The Agency’s Acting Director for the Office of External Affairs also called 20/20 “more entertainment and muckraking than news” in response to their reporting on Nazar.

As a result of having skipped out on bail and still being wanted in the United States, officials quickly determined that Nazar was unlikely to return. Once a bench warrant was issued, it seemed all but certain that he wouldn’t come back. After he missed the deposition for his lawsuit against TIME, the lawsuit was dismissed by a U.S. District Court Judge.

Once Nazar had returned to Mexico, the FBI’s Special Agents in San Diego - at least some of whom had worked on the case and participated in the arrest of Nazar - were warned “not to enter Mexico for safety reasons.”

The perceived danger was likely real. Another memo referred to a specific threat against the FBI and/or the DEA in relation to the case.

In addition to his more common criminal activities and threats made against law enforcement, Nazar was known for his considerable role in Mexico’s Dirty War, which saw the disappearance of an estimated 1,200 individuals. Nazar was personally infamous for his brutality and would be accused and tried for the disappearance of several high profile individuals. The United States, however, was unable to extradite Nazar despite the treaty that was in place, and the Government of Mexico declined to prosecute Nazar. He was prosecuted several years for his actions during the dirty war, though he would be acquitted apparently as a result of insufficient legal evidence.

By this time, Nazar’s career with the DFS was finished - though he would later return to the Mexican intelligence apparatus, where he would officially reconnect with its web of corruption, as discussed later.

For its part, the Agency offered a weak defense for its protection of Nazar. According to the defense the CIA and DOJ offered to the New York Times, the story had been “misreported, [and the CIA] exerted absolutely no pressure on Justice to protect Mr. Nassar Haro, and merely responded properly to a legitimate query from the Criminal Division. Mark Richard, an old pro at the division, resolutely confirms the C.I.A. account, and explains that the indictment was originally blocked because the department wanted to be sure that no ‘’greymail’‘ - threats to expose national secrets - would be used in the defense, and to make that determination required delays.”

The Agency’s explanation seems to ring only half true. Nazar’s known activities involving the Agency not only stretched back decades, but were also very recent and potentially damaging. Nazar’s knowledge not only would have let him use graymail against the Agency, but given him enough information to fabricate especially damaging lies. These lies would’ve become both graymail and blackmail, as the Agency would need to use classified information to disprove allegations that Nazar could have made. These accusations could have not only resulted in embarrassment and the burning of CIA sources and methods, but the release of spies who had been imprisoned for providing information to Russia in the case that would form the basis for The Falcon and the Snowman.

Read Part Two here.

A portion of Nazar’s FBI file is embedded below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Azteca Noticas