25 years ago, following the release of Oliver Stone’s JFK, President George H.W. Bush signed the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992 into law.

On October 26th, the law will hit its final deadline for the release of almost all records related to the assassination of Kennedy. The one exception is if the president explicitly agrees to block release of some specific files. Which, in typical fashion, the President has taken to Twitter to weigh in on:

Subject to the receipt of further information, I will be allowing, as President, the long blocked and classified JFK FILES to be opened.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 21, 2017

The National Archives and Records Administration, which is overseeing the release, seems a little less sure about things.

“At this point, things are still in flux. While we continue to plan for an online release by the deadline, it is unclear what will be part of the release,” wrote Miriam Kleiman, Program Director for Public Affairs for the NARA, in an email. “In regards to any possible postponement requests, because agency appeals are not public, we cannot share that information.”

She also highlighted a recent article in the National Archive’s Prologue magazine about the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection.

She said that the NARA was not granting interviews at this time.

After 25 years, still plenty of unanswered questions

While few experts expected any smoking guns, the release is still likely to be substantial and shed light on material of interest to historians, even beyond those interested in the assassination itself.

“It was one of the strongest disclosure laws ever,” said Jefferson Morley, editor of JFK Facts and author of CIA & JFK: The Secret Assassination Files. He said that between 1994 and 1998, the law lead to the release of about four million pages, but that, until this final deadline, agencies still had a fair amount of latitude in pushing off the release of information they deemed a national security risk or NBR: “Not believed relevant.”

That 25-year trickle of information might explain part of why the releases still garner so much interest.

“I’ve been surprised. I thought when the 50th came and went that would be it [in terms of interest’,” said Rex Bradford of the Mary Ferrell Foundation. “It never seems to flag to the extent that I thought it would.”

Surprises have included details such as Kennedy having approved plans to withdraw from Vietnam, as well as previously undisclosed information on U.S. involvement in Cuba and Mexico.

It’s also allowed researchers to get a rare view into the workings of the U.S. intelligence community.

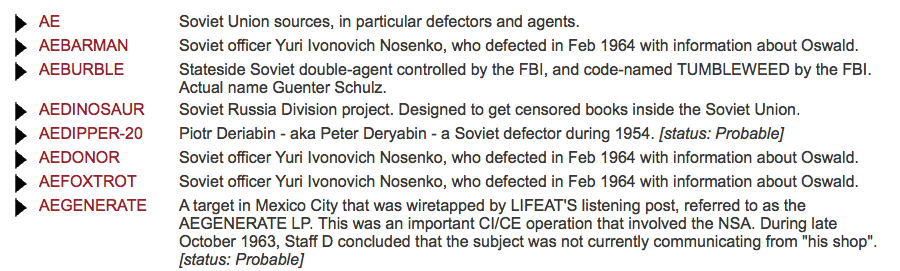

On of the Mary Ferrell Foundation’s projects, for example, is a cryptonym dictionary, matching intelligence codewords with the programs they represent.

The sheer breadth of the records means that every new generation finds something useful in the documents.

“What was of the greatest interest to researchers of some time in the past is no longer the focal part of the inquiry,” said James Lesar, cofounder of the The Assassination Archives and Research Center. “In a sense the Review Board was shooting a moving target. This release is very important.”

Even the number of documents targeted for release has been a moving target.

“My perspective on it is that you can’t rely on the National Archives or government agencies to get anything done by that date,” Lesar said. “Back in 2007, when I was representing Jefferson Morley, I forced the CIA to state the number of entirely withheld documents that remained, in their view, exempt until 2017. They came out with a number of 700 basically. A couple of years later they changed it to 774 or something close to that.”

Life imitates art

Lingering questions regarding the assassination of Kennedy came to a head after Stone’s 1991 movie. While Stone said in interviews that he had theories about who was responsible Kennedy’s assassination, primarily he wanted the release of documents to the public.

I think we should follow the example of today’s Russia, Rumania, and East Germany. I think we should invade the CIA and the FBI, and get these files out. Get the military intelligence files out on Lee Harvey Oswald; get the military intelligence files on Jack Kennedy that day in Dallas - why the security precautions were what they were. There’s so much that they never gave to the Warren Commission. We should get the House Select Committee to release its files that are embargoed till 2029. They could just take a vote now, and release all those files. It only takes one congressman.

To that point, releases had been highly selective and, some researchers felt, contradictory or misleading. Stone’s wish to “invade” the files of the CIA and FBI came true … with some important caveats.

JFK Records Act, which passed the year after the movie came out, had NARA create the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection. The mandate was broad: Collect all materials relating to the Kennedy assassination, as well as any materials gathered or used by federal, state, or local law enforcement in connection with the investigation into the assassination.

The Act also created the Assassination Records Review Board to assess materials for release while reviewing agency objections; some materials, such as sources’ names or information that would compromise national security, were withheld after review.

The ARRB released millions of pages of material while it was active from 1994 to 1998, but many of those records were partially redacted. Theoretically, those redactions come off Thursday.

Resources to dig in

For those looking to explore the documents, we’re collecting resources here. Have something we missed? Let us know

- On Friday, we’re hosting a Slack chat focused exclusively on the release. Share what you’ve found, hear tips from others, and discuss the latest news about the release

- NARA’s FAQ on the JFK Assassination Records Processing Project

- The Mary Ferrell Foundation’s cryptonym dictionary

- The Mary Ferrell Foundation’s document archive

- The Mary Ferrell Foundation’s JFK Database Explorer

- The Mary Ferrell Foundation’s 2017 release archive

Image via Wikimedia Commons