Public records aficionados know they’re in for a waiting game - requests can take weeks or years to get a response. In a 24-hour news cycle, how are last week’s documents still relevant?

In this week’s FOIA roundup, we see a reporter use a records request to revisit a story to get the background, reporters in Florida who actually just spent months investigating private schools and uncovered chilling details of abuse and neglect, and a reporter who found out the details of a secret $75,000 racial discrimination settlement, a year later. Old news matters.

Seen a great FOIA-based news story? Let us know and maybe we can include it in our next roundup! Send it over via email, on Twitter, or on Facebook.

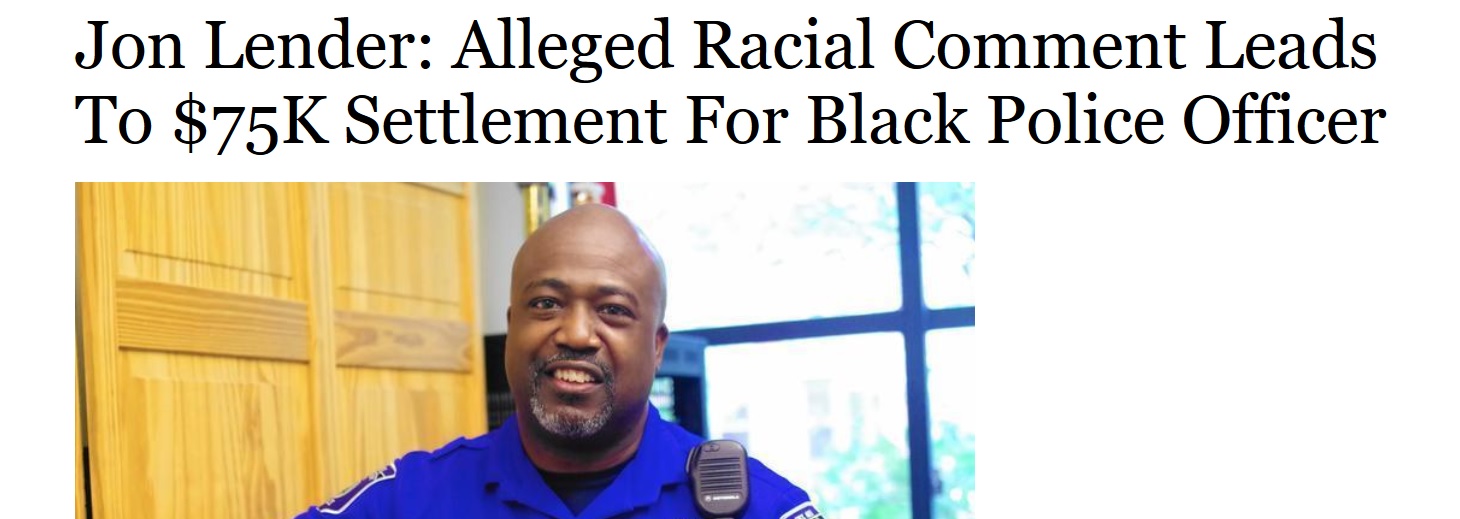

FOIA beats NDA

Jon Lender, a reporter at the Hartford Courant, found out that a Connecticut police officer was paid around $75,000 to settle a racial discrimination lawsuit in 2016.

The settlement included wording that forbid anyone involved from saying the amount that the town paid out.

But the settlement was still subject to public records laws in Connecticut. Lender recommended that reporters file for these kinds of settlements regularly and push back if denied. Just because the lawyers include non-disclosure terms doesn’t mean the documents are exempt from disclosure.

Want to try to file for a settlement? Clone this sample request:

However, Lender did caution against sending out careless requests for information.

“If you just keep firing blanks in the form of these indiscriminate, blind requests, you run the risk of being put at the end of the line as time goes on, and having to wait months before getting a response to your future requests - even ones in which you have 100 percent certainty that the documents you want exist and are available,” wrote Lender in an email.

Follow up with a FOIA story

Meredith Wadman, a reporter for Science magazine, used FOIA to figure out why exactly the National Institutes of Health failed to renew a firearms research program. In September, she found out the program had lost funding and filed a request for emails related to the program. She didn’t hear back in time for her first story, but a month later she was able write a follow-up based on the emails she received. Wadman found that several staff members voiced their support for the program, but it hasn’t been renewed for political reasons:

Jane Pearson, chairperson of the suicide research consortium at NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health, faced similar requests. “I have potential grantees asking,” she wrote to Peggy Murray, director of the Global Alcohol Research Program at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Murray was game. She wrote to a colleague: “We could renew it if other institutes and centers want to. We do.” But the staff hit resistance to the program’s title from George Koob, director of NIAAA, the institute coordinating the program. He wanted the word “firearm” removed before renewal. “That’s too bad,” Maholmes wrote to Murray. “We have so little firearms research. This program announcement called attention to that.”

Wadman said in an email that she thinks her request was answered so quickly because she had a very specific time frame in mind—she recommends that requesters not be afraid to ask a FOIA officer for help in narrowing down a request. She eventually submitted as thorough of a request as possible.

“I also tried to make FOIA staff’s lives easier by providing them with as much information as possible: links to the announcements; their titles; their official numbers; and the background: Obama had urged federal agencies to do gun research on the heels of the Sandy Hook murders, so I linked to his memo on that.”

If multiple agencies might have the documents you’re looking for, Wadman recommends submitting requests to both. One might be faster than another.

See what requests for information the NIH has received in 2017 here .

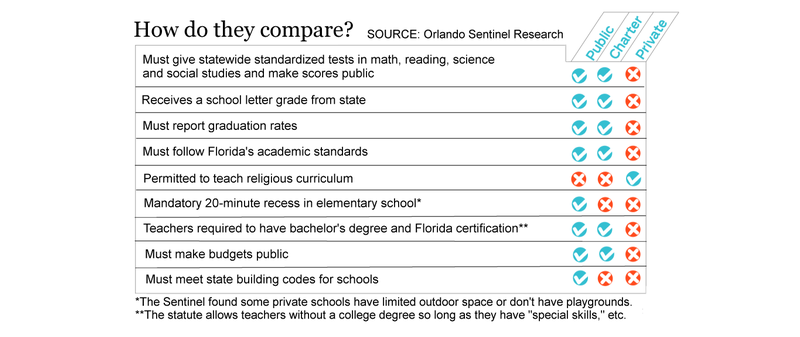

Little private school oversight, until the Sentinel came along

Leslie Postal, Beth Kassab and Annie Martin, reporters for the Orlando Sentinel, found out that Florida private schools get almost a billion dollars in state funding through voucher programs, but have almost no oversight. In order to produce this three-part series, the reporters reviewed thousands of pages of public records.

They found that 19 schools had falsified health or fire safety records - some had the inspector’s name forged or the dates. The reporters found many cases of unfit educators:

Samuel Vidal, who ran a private Christian school in Brevard with his wife, shut down his campus last year after a student told police he had improperly touched her. Vidal and his wife then opened a new school under a different name and continued to take scholarship students.

The department said the first school was registered under Vidal’s name and the second under his wife’s, so it did not realize the connection.

Palm Bay police arrested Vidal in February and charged him with lewd or lascivious molestation. Vidal, through his attorney, denied the allegations. After the arrest, the education department revoked the second school’s scholarships. But this summer, the department approved scholarships for yet another new school run by people with ties to Vidal, though his wife said she and her husband don’t have a role on that campus.

Again and again, serious investigative reporting projects weave together information from public records, interviews, and data to tell a full story.

Send us your favorite FOIA stories via email , on Twitter , or on Facebook , and maybe we’ll include them in the next roundup.

Image via Pexels