Last night, after a quarter century of waiting, the “final” batch of records related to the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992 was released to the public. Response from the transparency community so far has been underwhelming, to put it mildly.

(12) This is mostly my attitude so far of reading through all these "new" JFK files, & realizing what is still missing pic.twitter.com/1qmgnzMhLR

— Mark S. Zaid (@MarkSZaidEsq) October 27, 2017

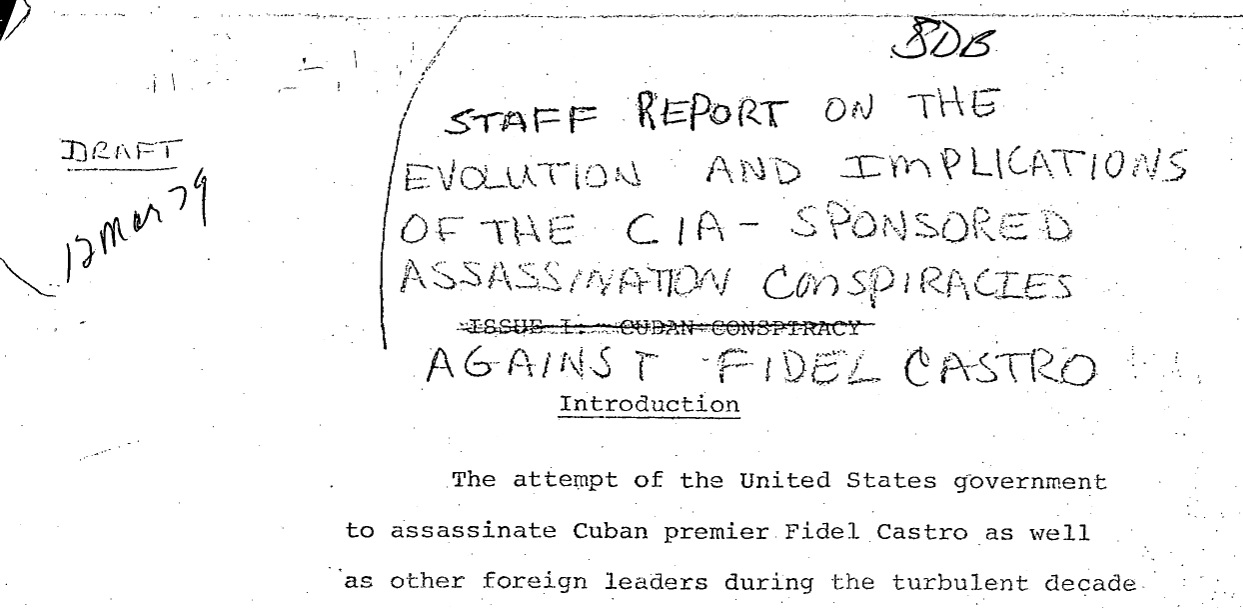

At the last minute, the most eagerly anticipated records were withheld for another 180 days review …

The CIA's #JFKFiles include 151-page transcript of the 9/12/75 Church Committee testimony of James Angleton. It was not released.

— Jefferson Morley (@jeffersonmorley) October 27, 2017

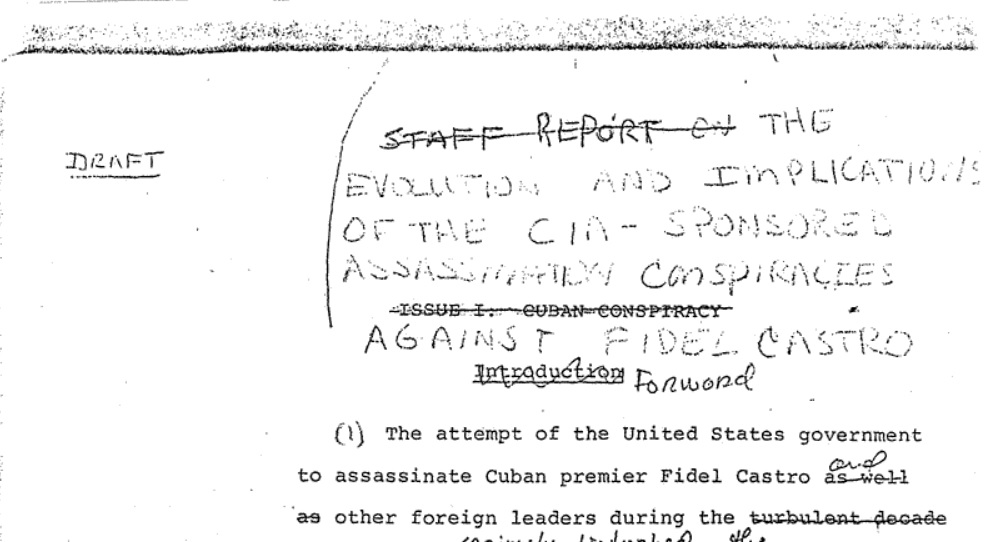

while some of the supposedly “new releases”…

had been previously declassified, some for decades …

and still others were, in the words of National Archives’ own metadata, “illegible.”

All of which begs the question - why, 50 years after JFK’s death, should we have waited so long to get so little of what should have already been available to the public in the first place?

Biggest takeaway from #jfkfiles rls will be that vast vast majority of classified historic dox can be rlsed with no harm and *much* benefit.

— NSA Nate (@NSANate) October 26, 2017

MuckRock previously dealt with this question when it came to CREST, Central Intelligence Agency’s declassified archives. For years, the only way to access these invaluable historical records was to physically drive to an auxiliary National Archives building in Maryland and use one of a handful of terminals, all while submitting to being filmed by the Agency in the off-chance you were an “enemy” planning on using them for “nefarious” means. When we asked for a copy, the Agency fell back on that argument, saying that it needed to keep track of everyone who accessed the records just in case they might be abused.

Even after losing that one in court and being forced to make their archives public (which they claimed was their idea all along), the CIA liberally applies a “need to know basis” to nominally public records, reclassifying material it finds embarrassing or applying its “sources and methods” stamp so arbitrarily as to render the concept meaningless.

While we at MuckRock like to highlight absurd examples of redactions and silly finds from the archives because, hey, a classified fudge recipe is funny no matter how you slice it, there’s deeply serious motive at the heart of all our transparency work. Giving government agencies complete control over the public’s knowledge of what they’ve done in our name - even decades after the fact - is to sign away one’s history. Taking the CIA’s argument to its logical conclusion, because “bad people” might benefit from knowing what the U.S. government has done, then it’s in everyone’s best interests for nobody to know - which is a violence to the very concept of transparency as a means of oversight.

As I seriously joked yesterday on Twitter, “Those who cannot remember the ████ are condemned to repeat it.”

Really annoying that stories on the JFK files are framed around "conspiracy theorists." How about this info shouldn't be secret for 50 yrs? pic.twitter.com/SIMDXr28kA

— Trevor Timm (@trevortimm) October 26, 2017

Rather than tacitly taking the government’s arguments that what’s hidden should remain hidden at face value, we should take the Freedom of Information Act at its most literal and remind these agencies “their” records are in fact “our” records. And that if you’re gonna claim every tasteless office prank is a matter of national security, it could and should hurt your argument for why it’s not in the public’s right to know. Especially 50 years after the fact.

Thanks to Emma Best for her help with this piece.

Image by Truthout via Flickr and licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 2.0.