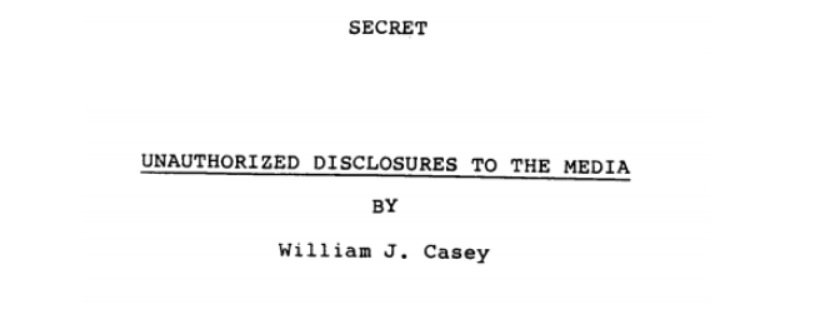

Just months before the government’s first successful use of the Espionage Act against someone for leaking to the media, a declassified report written by then-Central Intelligence Agency Director William Casey argued that just such an act would be irresponsible.

In the formerly SECRET paper, the Director stated that using the Espionage Act against media leakers was like “driving tacks with a sledge hammer” - grossly excessive. Months later, the government did just that, setting a precedent which is still used today. Two years later, Reagan’s war against leakers had pushed Casey into the even more aggressive position of threatening not just leakers with prosecution - but the Washington Post, the Washington Times, the New York Times, Time and Newsweek as well.

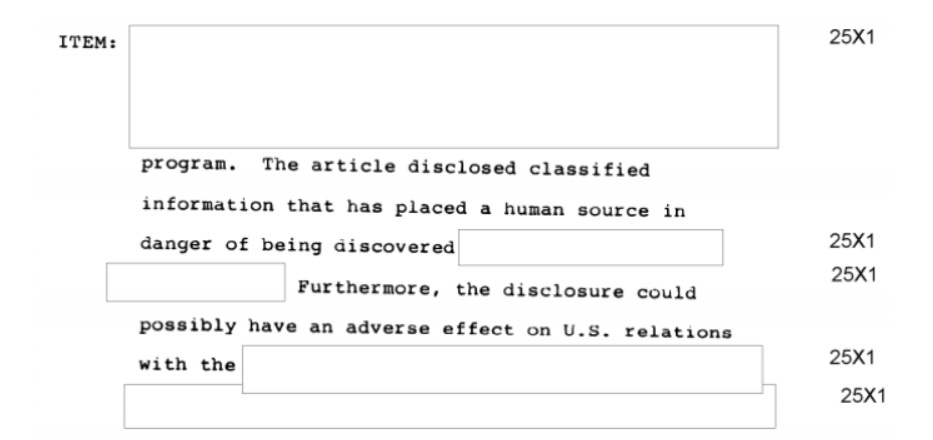

Far from minimizing the potential harm of national security leaks, Casey emphasized the damage that they could do. However, none of the five examples provided by Casey in his report resulted in any actual harm. Two examples “could have” resulted in adversary adjusting their techniques, though the language implies that hadn’t happened. A third and fourth example resulted in potential damage which forced the Agency to cut off contact with a human source lest that danger be amplified. While endangering human sources is never a good thing and disrupting HUMINT operations was unlikely to have been the intention, the report again indicates that no actual harm came to anyone. A fifth example placed someone in danger of being discovered, again a possibility which hadn’t come to pass, though it “could possibly have an adverse effect on U.S. relations” with an unknown group.

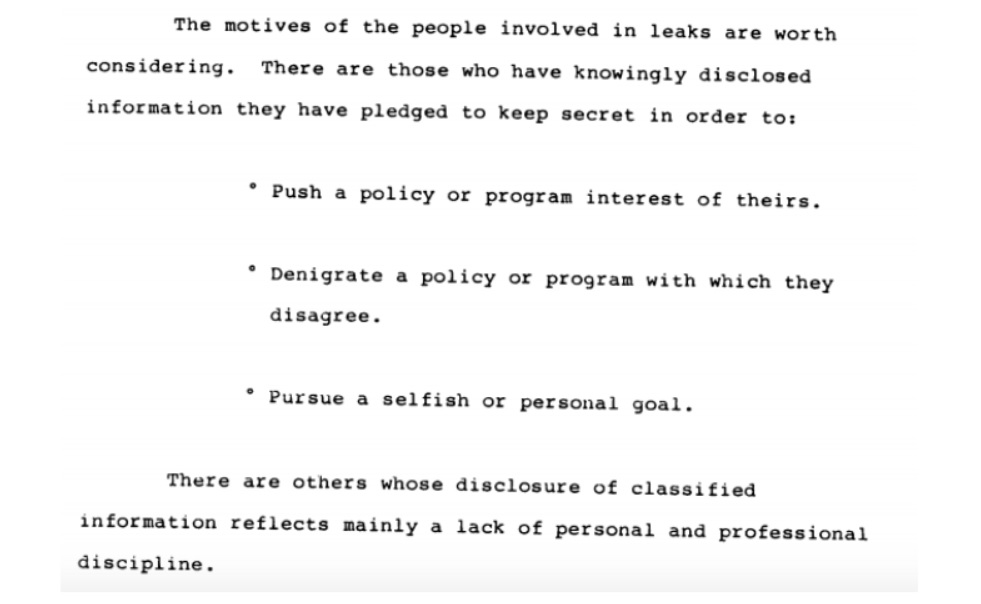

Casey took the time to point out that aside from a lack of discipline and professionalism, some leakers had specific motives, such as pushing a particular program or policy over another one.

Far from painting the media as the enemies of the public, Casey acknowledged that they were conflicted between their duties. Nevertheless, he conceded that it’s the job of the media to inform the public.

This concession didn’t stop him from also arguing that journalists be prosecuted and held in contempt if they refused to divulge their sources.

Casey also cited a legal argument that journalists do not have any legal protections for privileged communications, unlike doctors, lawyers and members of the clergy. As a result, they felt that a journalist could be “brought before a grand jury, given immunity from prosecution and can be compelled to identify the source of classified information.” However, care would need to be taken “to avoid making a journalist [into] a martyr.” To this end, a daily fine should be levied against the publisher until the questions were answered, rather than the journalist themself, which Casey felt was “legally feasible.” Casey also proposed a special prosecutor, an idea which was being explored by CIA elsewhere.

Curiously, Casey felt that this would not be “directed at the media, but at requiring the cleared government employee or contractor to live up to [their obligations].” How a measure that would directly fine publishers would impact the leaker would remain entirely unaffected, Casey failed to explain.

Casey also proposed legislation that would make the mere unauthorized possession of classified material a crime. At the time, this would put at risk anyone reading a New York Times article that reprinted classified material. Today, it would put anyone reading The Intercept or WikiLeaks at risk of potential prosecution, to say nothing of those involved in the outlets’ administration or distribution.

Despite his desire to see new legislation created that would specifically target media leaks (an all around better solution than bending preexisting laws to fill a role unintended by Congress), Casey argued against using the Espionage Act to prosecute leakers. Unlike specifically tailored and debated legislation, using the Espionage Act to target media leakers was excessive the same way that “driving tacks with a sledge hammer” was.

Ideally, Casey felt that the new law should not require they demonstrate that a leak caused any actual damage to the United States. Instead, the question should be whether or not the information was passed to someone not authorized to receive it.

Despite his desire to see the media prosecuted for their role in publishing leaks, Casey was not of the opinion that journalists are less patriotic than other Americans, though he added that “a few are less responsible than they should be.”

A memo to CIA’s General Counsel from the Chairman of the CIA Director’s Security Committee, written just months before Casey’s report, argued explicitly that while a “narrow legal standpoint” could potentially justify prosecuting media leakers under the Espionage Act, specific legislation was needed to properly deal with the problem.

Another memo written a few months before for the Director of the Intelligence Community Staff flatly stated that “no matter how one views it, this is a different crime from espionage.” It adds that “we should not drive tacks with a sledge hammer.”

Nevertheless, it would not be long before the Intelligence Community was doing just that.

Despite the misgivings in Casey’s edited paper about using the Espionage Act to target leakers, along with those expressed in the memo to CIA’s General Counsel, it was only a few months later that the government did just that by targeting Samuel Morison. This successful prosecution turned into a precedent used for decades, resulting in what Senator Moynihan called an “erratic application” the Espionage Act, which has since been used to target leakers and whistleblowers alike - and used to threaten media publishers themselves. To date, however, no such legislative solution has been passed. Instead, Reality Winner is charged under the Espionage Act for leaking a document to The Intercept.

You can read Casey’s full report on Unauthorized Disclosures to the Media below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image by Superior National Forest via Wikimedia Commons