Read Part 1 here

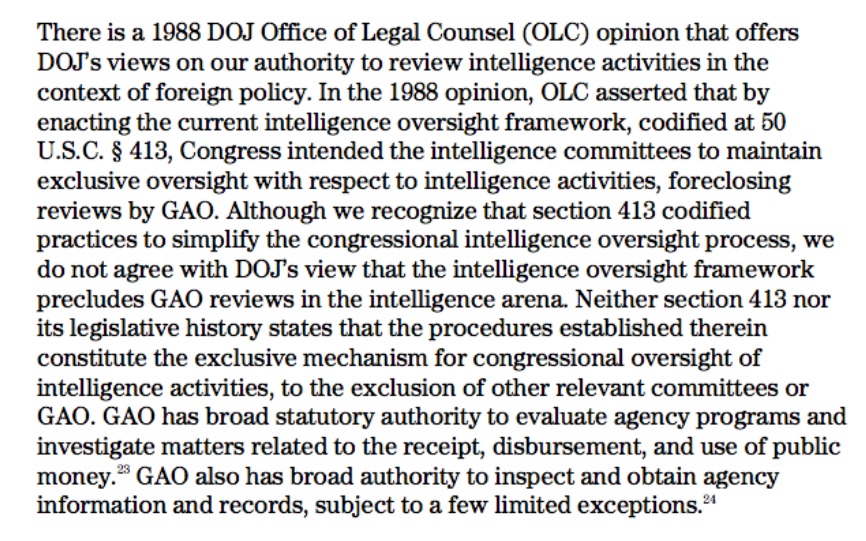

As a result of the failure by the Senate Intelligence Committee to restore the GAO’s authority to audit or review the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), by the next that immunity had spread to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), which had assumed some of the Agency’s responsibilities in coordinating the Intelligence Community. Like CIA, the ODNI cited a legally dubious position in a 1988 letter from the DOJ Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) stating that the GAO had no authority to look at anything relating to “intelligence activities.” Also like CIA, the ODNI used a such a broad definition of intelligence activities so that “by definition” they were categorically exempt.

The GAO noted that despite the argument being presented by both CIA and the ODNI, “neither section 413 nor its legislative history states that the procedures established therein constitute the exclusive mechanism for congressional oversight of intelligence activities, to the exclusion of other relevant committees or GAO.“ The OLC’s letter, which had been issued to help block the GAO probe on Noriega, offered a legal position which the GAO flatly rejected.

Regardless of the merits of the legal argument itself and accepting the OLC’s position arguendo, the GAO rightly disagreed with the ODNI’s position that their review involved intelligence activities anymore than CIA’s cafeteria does. The Project on Government Oversight similarly criticized the position, arguing that the ODNI was attempting to put itself entirely above GAO’s authority. POGO seconded the GAO’s argument against the ODNI’s position, which was the review wasn’t looking at “actual intelligence activities.” Regardless of their objections, the ODNI stood fast in its position, setting the stage for further denials of cooperation and outright obstruction of oversight activities.

In 2007 and 2008, several pushes were made to grant the GAO audit authority with regards to CIA and the Intelligence Community. Ultimately, the issue died despite a plea to the Chairmen of the Intelligence Committees. One of the chairmen, Senator John D. Rockefeller IV (D-WV), later overtly confirmed that he saw things as a competition with his Intelligence Committee, saying that GAO investigations were a “rather bad idea.” The Senator argued that “you can’t just sort of wander in and do this stuff like you’re investigating FAA weather stations.” Instead, he felt that his Senate Intelligence Committee should be given more oversight authority and the ability to appropriate funds.

Senator Pat Roberts (R-KS), at the same time, argued that “the GAO does precisely what the majority [in Congress] asks them to do.” Roberts said that the GAO shouldn’t be granted audit authority lest there be “further politicization of intelligence.” Senator Roberts was the Chairman of the Intelligence Committee before Senator Rockefeller, and the person who fired the entire Senate audit staff in what was regarded as a politically motivated move.

The GAO nearly gained its audit authority several years later. The 2010 Intelligence Authorization Act included a provision which would have finally granted the GAO the authority it needed to meaningfully and reliably contribute to oversight of CIA and the rest of the Intelligence Community. The provision, however, was dropped after President Obama threatened to veto it. Another amendment was similarly passed and attached to a Defense Spending bill to grant the House Intelligence Committee to “order GAO investigations on all subjects involving the intelligence community.” Nevertheless, a measure was passed that required the ODNI to formulate a policy on cooperating with the GAO. That policy would be issued at the end of April 2011, coming into effect at the end of June that year.

While the policy included several good points, such as instructions not to automatically categorically deny the GAO access to things (using language largely recycled from a much earlier DOD Directive), it received some criticism from the GAO. In a letter from the Comptroller General to DNI James Clapper, the Comptroller General points out that the language could easily be followed in an overly broad way that would “significantly hinder GAO’s ability to conduct related work that we are routinely requested by the Congress to do.” GAO’s criticism was justified, since the ODNI had interpreted similar language very broadly before to deny access to the GAO. Therefore, the GAO felt that they and the ODNI would have to carefully monitor and enforce the intent of the directive.

As further investigations revealed that the ODNI wasn’t capable of properly monitoring and reporting on itself, the ODNI didn’t revise or expand their guidance. The record shows that instead, the ODNI began to violate, or at least ignore, its own guidance. Part of the Directive requires that if the GAO provides a draft of one of their products to part of the Intelligence Community, they are “strongly encouraged to provide GAO with a timely response.” As a general rule, this meant seven to thirty days.

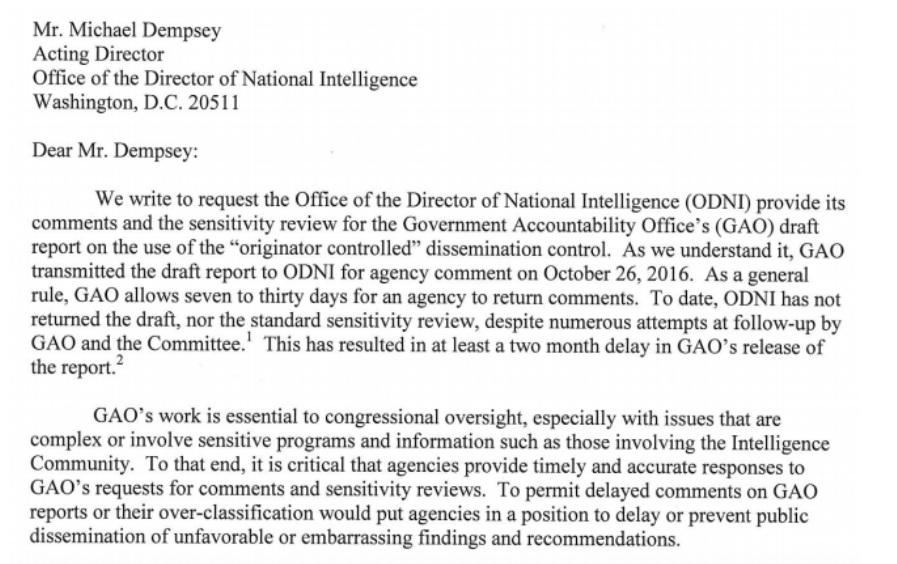

The ODNI was apparently free, however, to ignore this guidance, remaining silent for several months when the GAO asked them to review and comment on their report on the use of “originator controlled” dissemination controls. Since the request for comment was simply a courtesy but a necessary sensitivity and security review, the GAO was unable to proceed with the report without the ODNI’s cooperation. After several months of delay, Congressman Jason Chaffetz (R-UT) wrote in his capacity as the Chairman of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform to the ODNI urging a response. According to the Congressman’s letter, the ODNI had ignored “numerous attempts at follow-up” by both the GAO and the Committee, resulting in “at least a two month delay” in the report’s release.

The situation has not improved for CIA, either. Even when the information isn’t classified and the Agency isn’t exempt from releasing it, CIA refuses to report the data to the GAO on the basis that someone could learn about the Agency from it, “along with other publicly available information.” This is a return to the mosaic theory, which CIA and other Agencies have repeatedly used to block the release of unclassified and non-exempt information.

Unless Congress forces CIA to comply with GAO on all matters and makes it subject to GAO’s auditors, nothing will change. Unfortunately, Congress has never seemed willing to take the steps necessary to actually submit the Agency to oversight, and when it comes to the budget Congressional staffers and lawyers are “impressed” with how budget reprogramming (redirecting funds after they were appropriated for a specific purpose) “[goes] on all the time [in a way that] is not reflected” without a detailed audit.

The alternative would be for President Trump to order CIA to subject itself to GAO audits, but as of this writing the efforts to “drain the swamp” have been limited to hiring Goldman Sachs executives and have not moved onto improving government oversight.

Read the ODNI’s 2011 policy embedded below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via the Obama White House Archives