A field manual in Central Intelligence Agency’s archives, prepared under the direction of, and signed by “Wild Bill” Donovan, the head of the Office of Strategic Services, the World War II predecessor to CIA, explained how to use bribery and blackmail to destroy enemies and influence people.

Donovan, also known as the Father of Central Intelligence and the Father of American Intelligence, laid the groundwork for the American Intelligence Community and acted as a mentor to all of the most influential CIA Directors through the 1980s. Dubbed the Morale Operations Field Manual, the highly sensitive provisional manual was to be “used as the basic doctrine” for the OSS’ training. Its suggestions included using bribes to cause riots, trigger coups, and getting people hooked on drugs in order to bribe them with more.

While called “Morale Operations” in the book, the definition used more closely matches the popular understanding of psychological operations, or the U.S. military’s current definition of subversion. For the OSS’ purposes, morale operations included “all measures of subversion other than physical used to create confusion and division, and to undermine the morale and the political unity of the enemy.”

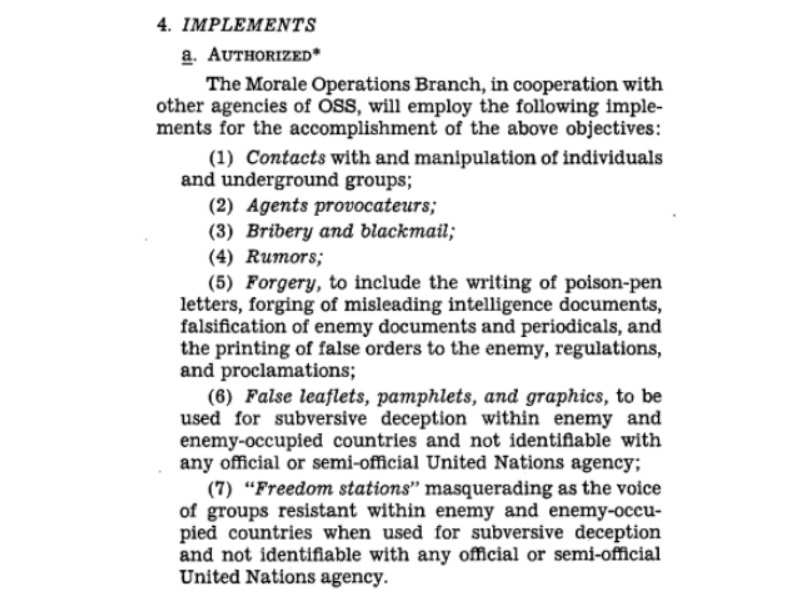

The authorized examples of morale operations were varied, but explicitly included bribery and blackmail.

According to the manual, bribery and blackmail could be “extremely effective” in many cases, but both were seen as dangerous. Bribery in particular was seen as likely to expose the operator, “since the art of double-crossing is an ancient one, and the bribed individual is apt to be an unscrupulous person willing to work for either side.” Bribery could be used to target “political and military leaders, newspaper editors and reporters, radio broadcasters, heads of business houses, religious, professional and labor leaders, police, petty officials, customs officers and sentries.”

Bribery’s uses were varied. In some instances, they could be used to accomplish “important strategic secret diplomatic acts,” but typically would be used to aid less ambitious operations. A bribe to a journalist or broadcaster, for instance, could be used to plant or help circulate rumors. The manual also notes that “bribing of police officials may facilitate the creation of an “incident” or riot.”

The “important strategic secret diplomatic acts” referenced above are discussed again in paragraph 33-e of the World War II manual, subtitled “Provoking Rebellion or Coup d’Etat in a Satellite Country or Inducing Its Separation from the Axis.” According to the manual, “the mission is to aid in the inciting and carrying through of revolutions, incidents, changes in governments or coup d’etat in satellite or other enemy-dominated countries.” The manual notes that due to the sensitive nature of overthrowing another country, “close consultation with the State Department may be necessary.” The manual, embedded at the end of the article, goes onto list several ways of accomplishing just such a goal.

Returning to the section on bribery, the manual explains that its judicious use with local leaders, “fence-sitting political, religious or professional groups” could help convince them to become subversives that would serve the U.S.’s goals. Similarly, selectively bribing officials could result in dissention being created in the organization. The manual also suggests bribing officials and then exposing the bribes to enemy authorities as a way of eliminating a troublesome person and creating “doubt and suspicion of all officials.”

When it came to actually bribing people, Donovan’s manual notes that it’s often best to start small and with minimal risk. This allows the recipient of the bribe to become accustomed to the idea, and creates a potential for leverage. In addition to the prior suggestion of exposing a bribe to eliminate a troublesome official, the manual also suggests using evidence of the bribe as the basis for blackmail. “Once the initial bribe has been accepted, and evidence of such bribery has been obtained, the demands can become successively greater.” Whatever form the bribe took, it was important that it “become increasingly indispensable to the recipient.”

In some instances, this meant providing something other than money, whether that meant food, medicine, drugs, clothes, liquor, jobs, transportation, protection, favors, etc. The manual notes that in the instance of drugs, it “may involve first inducing a dependency in the individual upon a drug.”

The manual explains that some bribes are best left covert and deniable. Techniques suggested, which are still used today both by intelligence agencies and organized crime, included buying goods above their value or selling them below it, deliberately losing a bet, presenting people with expensive gifts or loans, as well as “monopolistic rights to certain revenues, products or services; establishing “philanthropic” organizations as fronts; [and] subsidizing corporations.”

Regardless of who the target was, the manual notes that good intelligence is required. A successful bribe relied on understanding and exploiting the recipient’s “needs, weaknesses, grievances, fears, hopes, honesty, and integrity.”

The section describing blackmail is comparatively short. Noting that it’s used “against the same targets and can be used for the same purposes as bribery,” the manual explains that threats are a stick that can be used in conjunction with, or in place of, the carrot. A typical blackmail threat would be release information about them that would cause them harm. Whether or not the information was accurate didn’t necessarily matter. If the subject could be made to believe that it was, or convincing evidence fabricated, the end result would be the same.

Expanding on the idea introduced in the section on bribery, the manual explains that blackmail is often the second stage of a bribe. Once someone had accepted a bribe, additional bribes could be used alongside the threat of exposure, creating a bribery-blackmail one-two punch. The continuing use of bribes would often be necessary due to the need to keep the persuasion proportionate to the risk. If the risk of being exposed was less than the risk they would undertake by acquiescing to the blackmail, it was doomed to fail. A bribe could make up the difference in motivations.

Ideally, blackmail should be genuine and based off of intelligence that have exposed the individual’s vulnerabilities. However, there were bound to be times “when incriminating information is difficult to secure, or when no such information exists.” In these instances, “it may be possible either to create it or to plant it.” This would, of course, be the most difficult and dangerous route to take.

With patience, timing and careful selection there were few subversive goals that the manual didn’t think could be accomplished with bribery and/or blackmail. Everyone had a weakness, and it was up to American intelligence to find and exploit it. In those instances where no weakness existed, it could be created either by fabricating evidence, or by getting them hooked on drugs.

Of course, most of the activities described in the manual would be illegal if undertaken by a private citizen. MuckRock is not responsible if you follow the advice of the Father of Central Intelligence.

You can read the full manual embedded below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via the Obama White House Archives