A document in Central Intelligence Retirees Association’s archive points to the existence of an unofficial “Common Interest Network” of retired intelligence officers. The network, also known as CIN - “as in living-in-sin” according to one of its founders - exists to coordinate the efforts of different organizations. Described as “an unofficial Intelligence Community,” it doesn’t exist except as an abstract, with no chairman, no agenda, and “not even the formality of a rotating host list.” Yet it exists, meeting to discuss influencing Congress and the press, to successfully attack the Freedom of Information Act, and to coordinate the efforts of the organizations that make up the Common Interest Network.

Captain Richard Bates, who was the president of two organizations making up the Common Interest Network, a board member on another three of its organizations, and the man who ran CIN for a time, wrote that it “is a network. It is not an organization. It has no charter, no list of officers, no bylaws, no regular obligations, and it does not contemplate acquiring any.” According to Ray Cline, a principle member of CIN, the acronym was appropriate because it would inevitably be pronounced “as in living-in-sin.” Captain Bates added that “CIN is a network … a loose, informal but regular gathering of representatives of the organizations with offices in the Washington area.”

According to Captain Bates and CIA historian Thomas Troy, CIN’s prehistory can be traced to a response to the “ceaseless round of accusations, investigations, revelations, and condemnations of the intelligence agencies.” The investigations conducted by Congress were explicitly cited as one of factors that lead to the creation of organization of organizations by retired intelligence officers. Some of these investigations into the wrongdoings of the intelligence agencies were seen, within the community, as threatening the Agency with its own personal Holocaust. The retired intelligence officers “found natural allies [in] retired military, defense specialists, some academicians, [and] public-spirit citizens.”

The result was, according to Thomas Troy, was “more than a baker’s dozen of either new intelligence organizations or old organizations with a new interest in intelligence.” This led to so much “talking, meeting, fund raising, and promoting of causes and projects” that retired Ambassador Durbrow finally called “for some coordination.” While there was some talk of a super-organization, or of combining organizations, these discussions largely went no where until the early 1980s.

During the National Military Intelligence Association’s (NMIA) 1981 convention, held at the National Defense University, leaders from four of the largest intelligence groups “discussed the profession, and particularly the role of their organizations.” Joined by the National Intelligence Study Center (NISC), the Association of Former Intelligence Officers (AFIO) and the Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association (AFCEA), the groups were able to agree that “there could be no super-organization, but that there should be some sort of information coordinating effort.” They suggested “a periodic luncheon meeting” to make sure they all “barked in unison.”

It took another fourteen months before the Common Interest Network began to take shape. In December 1982, the AFIO sent out invitations to the “leaders of several intelligence, and intelligence related, organizations.” The NISC supported the initiative, offering “to serve as an informal clearinghouse for information and to help coordinate the scheduling of meetings of all [the] organizations.” In total, “about fifteen persons” accepted the invitations.

Finally, “enter CIN.”

In 1986, there were at least fifteen organizations that making up CIN, with one source stating that it’s made up of “some sixteen intelligence organizations.” The first fourteen known organizations were American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on Law and National Security, the AFIO, the American Security Council, the AFCEA, the Association of Former Agents of the U.S. Secret Service, the Central Intelligence Retirees Association, the Conflict Analysis Group, the Consortium for the Study of Intelligence,the Hale Foundation, the NISC, the Naval Intelligence Professionals, the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI, the NSIC and the NMIA are all names of organizations which are unsurprisingly part of CIN. The final known “regular participant,” however, is unexpected: Accuracy In Media (AIM).

The inclusion of AIM within CIN is more than simply an anachronism, despite its National Advisory Board including the same Ambassador who had played a role in instigating CIN’s formation. Not only is AIM a media organization, it’s known for pushing a number of conspiracy theories, including the supposed “Clinton kill list”, anti-LGBTQ+ conspiracies, George Soros conspiracies, birtherism, and Shariah law. Its unexpected nature may also be the most revealing as to the extent of CIN’s activities and coordination.

Ray Wannall, a former intelligence officer and one of AFIO’s leaders, had his 1984 speaking tour sponsored by AIM, an occasion which was used “to strike some blows for the intelligence side.”

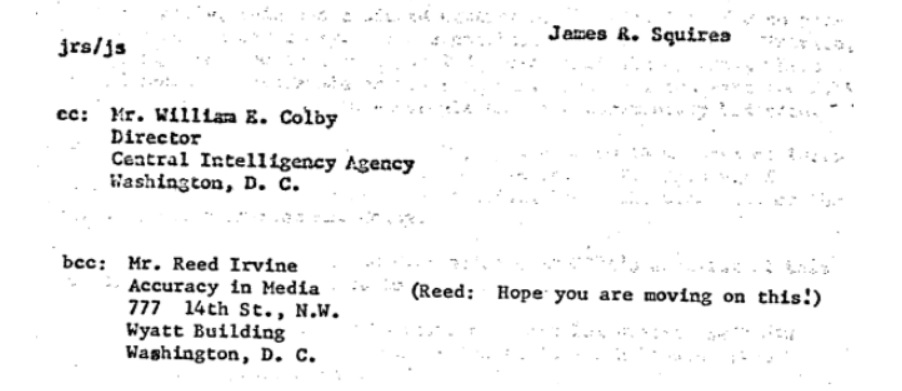

AIM appears several times throughout CIA’s archives, and with some examples including AIM’s private correspondence. In one 1985 example where AIM defends CIA and criticizes The Washington Post, copies of the letters wound up in the Agency’s possession through unknown channels. In another instance, carbon copies of letters defending the Agency were sent to CIA Director William Colby, with blind carbon copies being sent to Reed Irvine of AIM with the note “hope you are moving on this!”

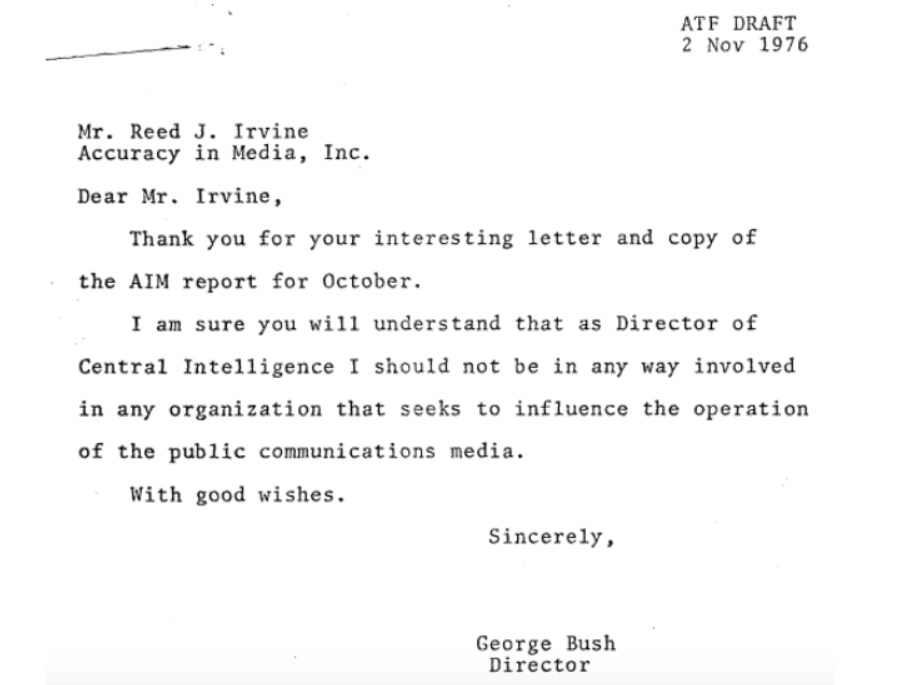

Whatever the extent of the Agency’s involvement with AIM, it is a sensitive subject. In 1976, AIM approached CIA Director George H.W. Bush asking him to join AIM. A letter was drafted or the Director, declining the acceptance and pointing out that the CIA Director “should not be in any way involved in any organization that seeks to influence the operation of the public communications media.” This may have still been seen as too much contact between the new freshman CIA Director, as an identical copy of the letter was sent and signed by his assistant instead.

Other documents point to additional coordination between AIM and other CIN members. AIM partnered with the Jamestown Foundation to send a Soviet defector on a speaking tour. In 1983, AIM’s founder had been a speaker at AFIO’s annual convention a few months after the formation of CIN. AIM’s founder, Reed Irvine, took the opportunity to comment on “the hostility of U.S. media in general to the Reagan administration.” At the time, AIM had been “sensitizing the public to unfair comment and bias by the major TV networks, of which CBS is the worst.” As it would turn out, AIM’s fight against CBS was also CIA’s fight against CBS.

As a result of CBS’ reporting on the Ron Rewald case, both AIM and CIA took CBS to task. In addition to AIM’s coverage of the case and repeated condemnations of CBS, the Agency filed a petition alleging that CBS “engaged in deliberate news distortion” in addition to violating the “Fairness Doctrine and the corollary Personal Attack Rules” with their reporting. The Agency’s court filing cited and quoted AIM’s reporting which alleged, in part, that “there is something very wrong with the management of ABC for failing to insist on a genuine investigation and prompt disclosure of the findings as soon as the CIA challenged its report.”

AIM’s indirect ties to CIA and direct association with CIN were not a one-time aberrations. As late as 1986, AIM was coordinating with other members of CIN to pressure media outlets into changing their coverage. According to one letter from the AFIO to AIM, and archived inexplicably in CIA’s files, several CIN members had worked together to pressure News-Press into “a complete volte-face [about-face] from the past positions of this newspaper.”

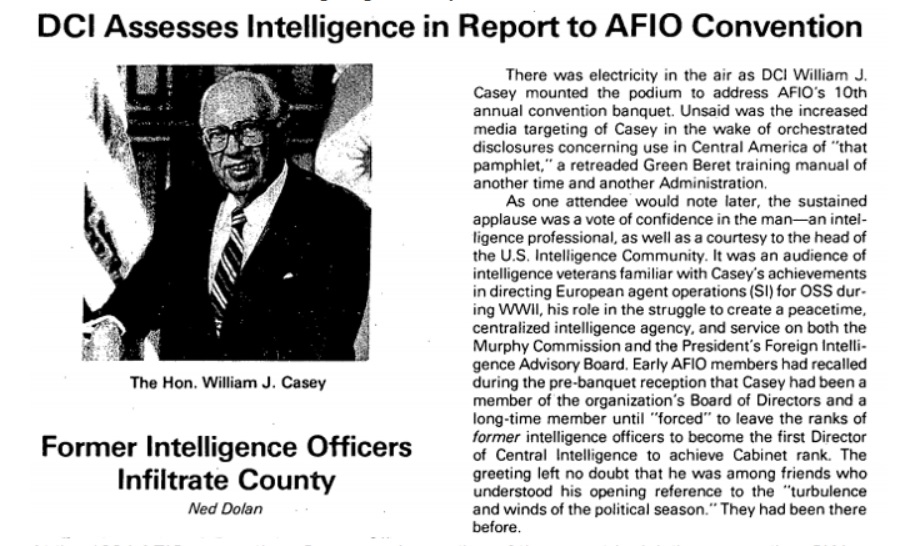

In 1984, Phil Nicolaides of Accuracy In Media served as the moderator for an “intensive seminar session [dealing] with the role of intelligence in combating terrorism.” The panel was put together by the AFIO for its annual convention, which hosted CIA Director Casey. The AFIO’s newsletter describing the event immediately made mention of what it said went “unsaid” - namely “the increased media targeting of Casey in the wake of orchestrated disclosures.”

At the 1984 AFIO convention, Casey made mention of the recent legislation exemption CIA’s operational files from the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), thanking the AFIO for its “stout support in this endeavor through legislative and media efforts” to alter the public’s view and understanding “of the proper role of intelligence.”

Another CIN member, The Hale Foundation, also took part in the effort to grant the Agency new exemptions from FOIA. According to their 1984 report, they had “directed major efforts” towards the legislation. The Hale Foundation was “proud to have helped along the way.” It’s very likely that their help was considerable. According to a Democratic Congressman quoted in the foundation’s report, “The efforts of The Hale Foundation to inform the Congress of the need to modify the application of the Freedom of Information Act ot the Central Intelligence Agency are greatly appreciated.”

The same report briefly mentions The Hale Foundation’s involvement with CIN.

CIN’s targeting of FOIA was far from incidental - according to Thomas Troy it was one of the topics where CIN sought “to achieve much unity” on from the beginning. The members of CIN not only succeeded in achieving unity, they successfully had the FOIA amended to exempt large portions of the Agency’s files from disclosure.

At each of its quarterly meetings, members of CIN would discuss the activities of their various organizations, comparing notes on their activities and coordinating “when they will meet, new projects, resolutions to be offered to the membership at conventions, and who will speak at meetings.” The members of CIN would also discuss, as they had with amending the FOIA to exempt CIA, “legislation before Congress.” Other topics included “how the press is reporting intelligence developments,” which may explain part of AIM’s involvement in it. According to Captain Bates, “no vote is taken, [but] from these meetings joint effort is often the result.”

CIN was last confirmed to be active in 2012 by Ronald Kessler, in the only publication outside of CIA’s archive to discuss CIN. According to Kessler, “there are a number of associations of retired intelligence officers, and all of them exchange information through an information organization known only as the Common Interest Network Luncheon…” It seems that Kessler barely scratched the surface of CIN. “As an informal, unofficial intelligence community, CIN has no intention of being the echo of the official intelligence community or any particular agency.” For educating the public and Congress, however, “CIN is getting behind it all.”

While CIN may not be a name known by many outside the group, it has furthered CIA policy, attacked the Agency’s enemies and granted the Agency previously unprecedented exemptions from the Freedom of Information Act.

You can read a copy of the 1986 history of CIN embedded below, along with some information on its members (excluding AIM):

Disclosure: The author has, in the past, been a member of several groups which make up CIN. This neither informed nor colored the reporting.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image by Marcel Oosterwijk via Wikimedia Commons and licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 2.0.