When I first began work on my grant, generously given by the Fund for Investigative Journalism, I intended a series of articles looking at how police militarization is evolving, its effects on communities, and its effects on the individuals who come into contact with it. Standing Rock was first on my list of destinations I wanted to travel to, so I could speak with victims of state violence and see the effects on the Native communities in North and South Dakota which bore the brunt of the law enforcement tactics. On my first trip in June out to the Dakotas, it very quickly became abundantly clear the story was much bigger, and the narrative far richer, than anything I had expected.

The reasons why water protectors were so adamant about stopping the Dakota Access Pipeline were all interwoven with the history of Native communities, are in turn central to how communities and individuals from these places have responded to months of tear gassing, pepper spray, police batons, flybys and other tactics used to suppress their right to protest. My thesis going into this grant was that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have come home to American soil. The counterinsurgency being waged in the Dakotas is the greatest evidence of this I’ve seen. And because of this, FIJ allowed me to change my plans, and head out for a second trip, this time a full week.

While there is so much more I have to write, and so many more hours of recording to transcribe, this piece will simply be a short travelogue of where I went, the people I saw, and the things I noticed. There is much more to come.

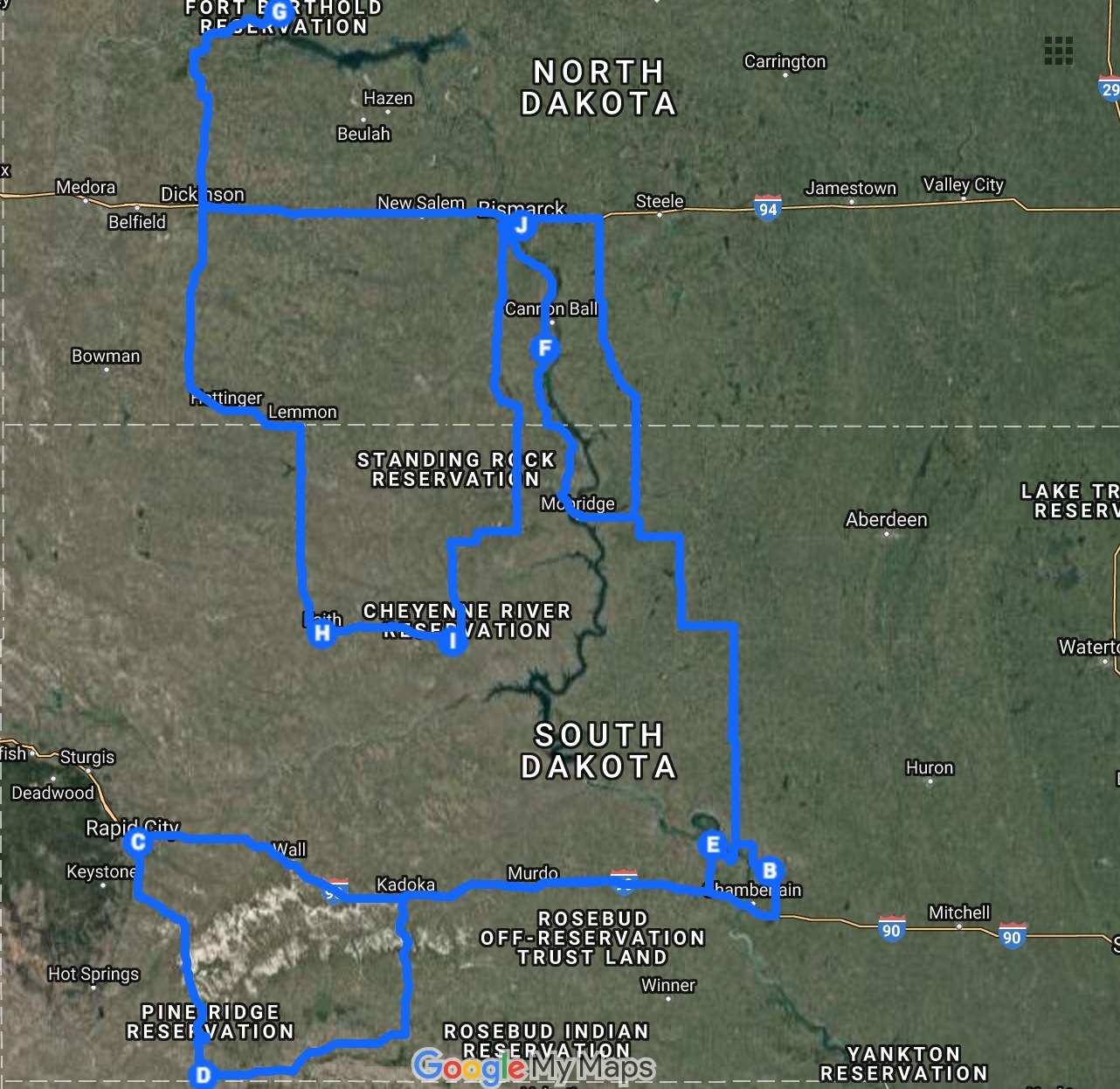

As one can see, I put an embarrassing amount of miles on my rental car, a Toyota Camry, which carried me through dirt roads and what seemed like near ceaseless driving. As an aside, I found the soundtrack to Hell or High Water makes for particularly good driving music in the Dakotas.

Upon arrival in Bismarck, North Dakota, I spent about an hour in the parking lot, calling sources, figuring out a game plan for the next few days. Then the driving began in earnest. South, through rolling prairie, rows of crops, and industrial agricultural structures, I drove until I reached the Crow Creek Reservation, home to just over a thousand mostly Mdewakantonwan Dakotas. There I spoke with Crow Creek Tribal Chairman Brandon Sazue, an environmental activist and water protector. His tribe contributed water protectors on horseback, and spoke to me at length about the counterinsurgency, Native sovereignty, conditions in jails for water protectors, the history of race relations in the area, and his activism.

His description of the jails - what he called, “glorified dog kennels” - is important in understanding that this was indeed a counterinsurgency. “What the cameras didn’t show you,” he said, “was in the back there were silhouettes, like of a human, and there were taser tips in them. And there were taser tips on the ground as well.” When I asked if people were getting tased in jail, he replied no, “I think it was more of a tactic.” This willingness to frighten already scared people, being led into jail, many for the first time in their lives, indicates a willing to intimidate through any means necessary. Like the pictures out of Abu Ghraib during the Iraq War, the message in both cases was strikingly similar: stop resisting or you will be punished severely.

The next morning, I drove three hours west to Rapid City and met up with Tanyan InajinWin, who I had met with in my first trip to the Dakotas. InajinWin was with a group of activists marching to a nearby Rapid City hospital, protesting the treatment of an Indigenous woman which had led to her death. As InajinWin explained, “Racism is in our medical services all over this area. People go in and never come back.”

InajinWin’s tireless activism against uranium mining and seismic testing for oil and gas in the Black Hills, a highly sacred place for Lakota people, led us away from the protest however, and further south we drove. We were going to Whiteclay, Nebraska, a tiny unincorporated community of 14 people, which sits just on the edge of the Pine Ridge Reservation, which was also the the site of a vital protest camp. Originally, Whiteclay was set up more or less exclusively to sell alcohol to those living on the dry Pine Ridge Reservation. InajinWin, a woman and mother originally the town of Oglala just northwest of Pine Ridge, was set to speak in Lincoln, Nebraska the following day at a hearing to decide whether Whiteclay would remain shut down.

While driving south, InajinWin gave me more history - what happened at Standing Rock most certainly did not happen in a vacuum. The more she spoke about the environmental degradation of Reservation lands, and the racism all too common in the region, the more I realized that Standing Rock was the boiling over of years of frustration at no coverage, and even less progress, in regards to the affairs of Native people in the U.S. Extreme poverty, toothless sovereignty rights whittled down for years by the U.S. government, and corporations plundering resources from Native lands had been the norm for decades, if not longer.

The author with water protector Helen Red Feather

At Whiteclay, once InajinWin had boarded her van taking her and other protesters south to Lincoln, I had the opportunity to speak to water protectors, young and old. These were people truly committed to uplifting their people, and protecting their resources and history. One elder named Helen Red Feather told me a story about nearly being arrested while chasing fallen frybread down a hill. She was laughing the whole time at the absurdity of the situation - an elder nearly arrested for simply going down a hill simply because she did not want good frybread to go to waste. As she put it, “the sun was so hot that day. I needed that frybread!”

I also spoke to a water protector named Anthony “SmudgeBear” Edwards. SmudgeBear as he came to be known at the camp, was a medic during the protest at Standing Rock. When I asked him to speak to me further about what that was like, he became emotional. “Seeing everyone come back, pouring that milk of magnesia in their eyes because of the OC and gas … fired at close range.”

From Whiteclay, I drove north late that night, back to Rapid City. In the morning I traveled to the Lower Brule Reservation, in the center of the state, the “E” on the map above. There, a growing number of people are gathering to oppose the planned Keystone XL pipeline, which would cross its path. Here I spoke to water protectors representing Lakota, Dakota, and Ojibwe tribes, including a few who were white. A campfire was made, and as the sun dipped below the prairie horizons, I heard stories from camp. I heard that from the last time I was there in June, the flybys by unmarked white Cessnas were increasing from once a week to now every two or three days. I heard about the bizarre phone activity, potentially indicative of heavy surveillance. I heard much more than this piece will allow, but I’ll be in touch with experts to discuss further what patterns in these stories may add up to.

All in all, it was a special evening on the prairie listening to these stories and watching the sun slip below the waves of grass, and the stars rise in the sky.

Read Part 2 here.

Image via Curtis Waltman