Documents in the Central Intelligence Agency’s declassified archive show that the Department of Justice had a list of 11 questions that they wanted answered before the Federal Bureau of Investigation would investigate an unauthorized disclosure. The questions not only highlight some of what the DOJ considered the crucial facts, they help show why so many federal leak cases are never prosecuted.

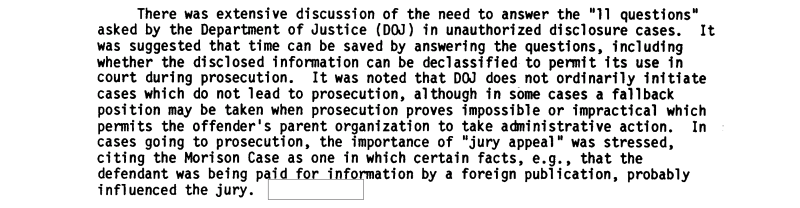

The questions are mentioned briefly in a 1987 seminar on unauthorized disclosure investigations, with “extensive discussion” centering around the need to answer the DOJ’s “11 questions.” One participant helpfully suggested the agency could save time by answering the questions. Another participant pointed out that the DOJ rarely pursued cases that weren’t likely to result in prosecution, but that the FBI was still authorized to investigate in cases that would result in an administrative action rather than prosecution.

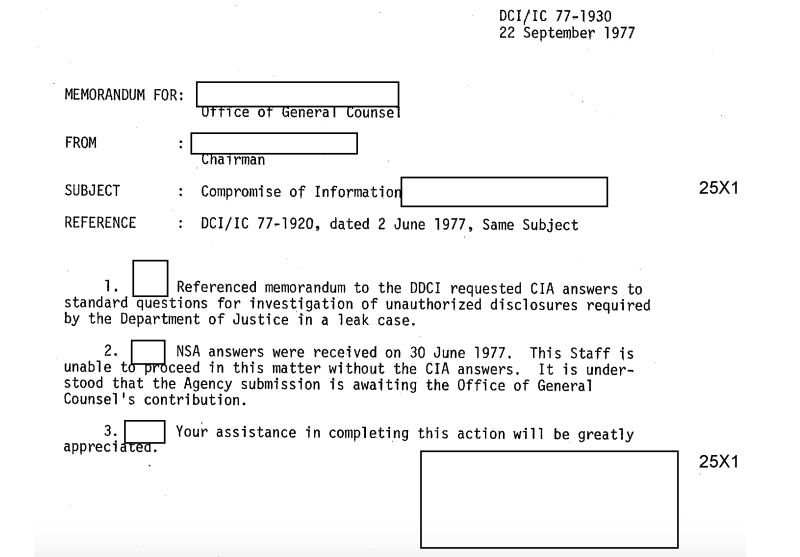

It’s not clear when the questions were first introduced, but they are mentioned by name in a redacted CIA memo from 1977.

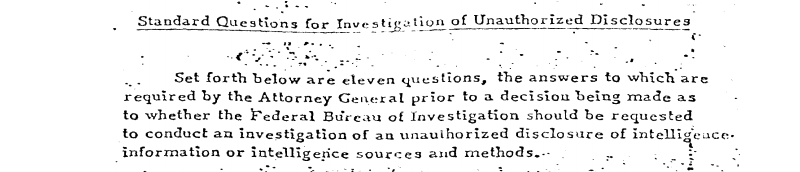

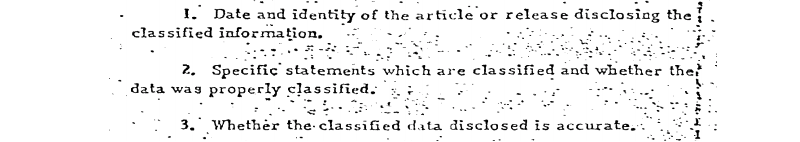

A copy of the Standard Questions for Investigation of Unauthorized Disclosure are included in CIA’s archives. According to the document, answers to the questions “are required by the Attorney General prior to a decision being made as to whether the Federal Bureau of Investigation should be requested to conduct an investigation.”

The first three questions are simple, and seemingly obvious - where did the occur, what exactly was the leak, and was the leak accurate. The initial questions on the list appear similar to, and somewhat overlap with, the questions on the form for CIA’s leak database.

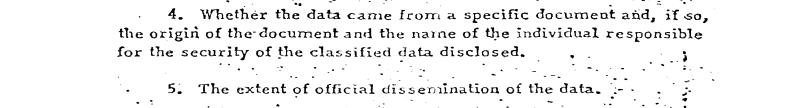

The purpose and necessity of the fourth and fifth questions are also rather obvious. Both questions inquire about who had access to the information.

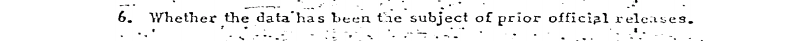

The sixth question, however, is a bit vexing - it asks whether or not the information had been the subject of an official, prior release. If the information had been officially released, it’s more difficult to see how it could be considered a leak or what the purpose of investigating the “leak” would be. While there are instances where information is improperly classified, investigating the leak of improperly classified (and already released) information would be - or at least should be - largely a waste of time.

The seventh question, whether anyone had requested permission to disclose it, creates a bit of an issue for the would-be leaker. While the benefit in discovering who had wanted the information released is obvious, it also creates a scenario where people are less likely to initially seek permission, because it could be used as evidence against them. On the one hand, they could be granted permission and avoid breaking the rules. On the other hand, they would be creating a trail that would lead directly to them.

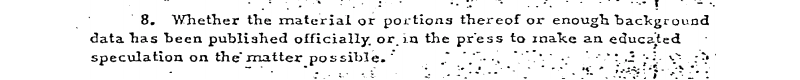

The eighth question deals with the problem of the mosaic, and indirectly questions whether or not it was an actual leak. Similar to the sixth question, it asks if the material had been officially published before. It also goes a step further, asking if enough parts of it or background information had been discussed in the press to allow people “to make an education speculation on the matter.” In other words, could people figure out the information from what was already out there? This question helps the DOJ decide not only whether or not it was a leak, but whether it would be worth prosecuting the offense.

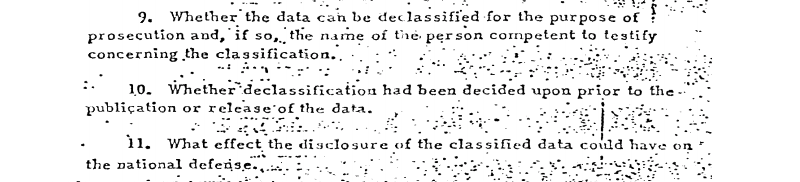

The final three questions mainly deal with the practicality and necessity of prosecution. Can the information be declassified enough to allow prosecution? Had the issue of declassification been decided before it was released? What effect could the disclosure have on national security?

While none of the questions are very surprising, they are informative. They not only outline the DOJ’s thinking and how they approach cases of unauthorized disclosure at the earliest stages, they show why most leak cases aren’t prosecuted. If the information is too widely disseminated, then the Bureau would have to rely on the journalist giving up their source - an unlikely event. If the information had been previously officially released, then both the intent and harm become questionable and prosecution becomes less important and less likely to succeed. Of course, not every where an investigation takes place results in a prosecution, further explaining the low number of prosecutions compared to the number of leaks to the press.

The 11 questions are embedded below.

Image via Warner Bros.