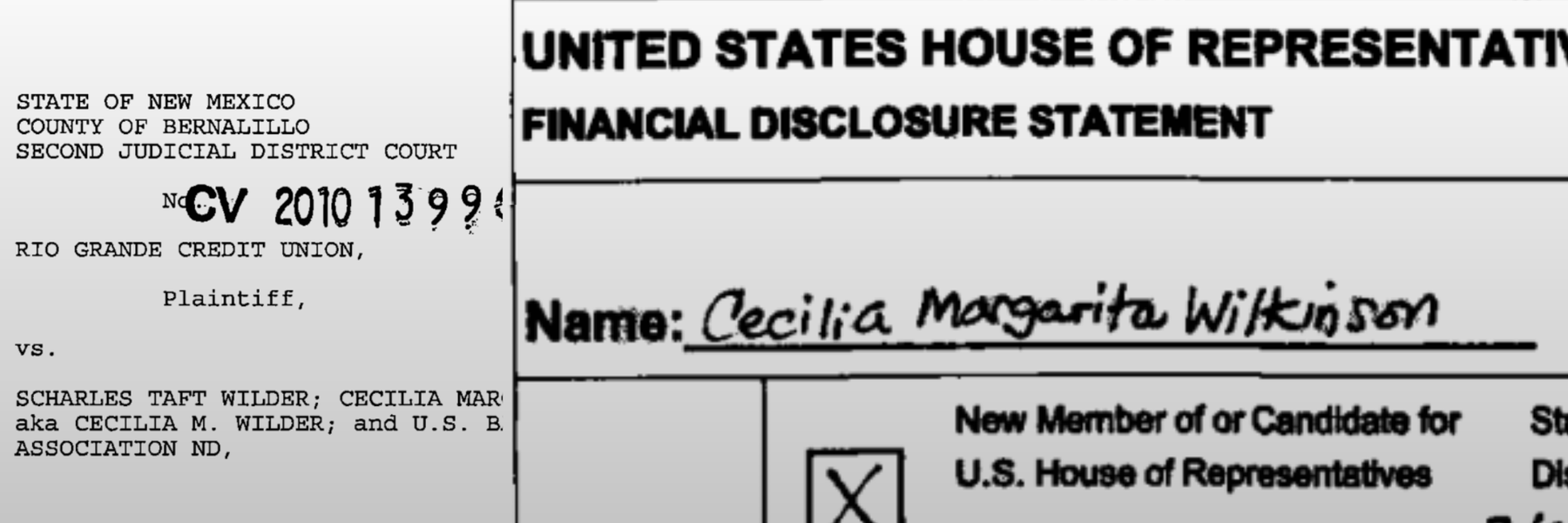

On Monday, The New York Times reported that Democratic Congressional candidate Abigail Spanberger had had a complete, unredacted copy of her federal security clearance application, known as an SF-86, released to a Republican opposition research group America Rising through a Freedom of Information Act request.

BuzzFeed.News later confirmed that the information came via a FOIA request and provided more details.

So for this special edition of our weekly round-up, we’re offer some background on what that means, how it might have happened, and the potential fall out.

What happened?

As outlined in the original BuzzFeed News article and in Christopher Burgess’ follow-up piece for ClearanceJobs.com, a rough timeline provided by the Congressional Leadership Fund, the super PAC America Rising provided the documents to:

-

On July 9th, 2018 America Rising submitted a FOIA request to the National Personnel Records Center for “records reflecting Ms. Spanberger’s employment dates, annual salaries, title, and position description.” Why would NPRC have her records? Spanberger is a former Central Intelligence Officer and agent with the US Postal Inspection Service, the law enforcement wing of the USPS.

-

Three days later, on July 12th, the NPRC wrote a letter to America Rising, informing them that their request had been forwarded to the USPS. This is extremely common practice within the FOIA process.

-

A little under three weeks later, on the July 30th, USPS releases to America Rising Spanberger’s entire UPIS personnel folder, including the SF-86 she filled out prior to employment, without any redactions. This is extremely uncommon practice, if not unprecedented.

So what’s the big deal? We’ll break it down in increasing order of weirdness.

The timeframe

America Rising’s request was processed incredibly quickly when you consider that the UPIS and USPS have average response times of 71 and 114 days, respectively, according to MuckRock’s internal tracking numbers. For context MuckRock’s Michael Morisy has an outstanding request from 2013 that USPS requested an extension on just last December. They even sent a dubiously legal “still interested letter” asking if he’d be willing to close out the request after nearly four years of radio silence. So less than a month for responsive records and then some is quick.

The privacy issue

As we’ve written about before, it’s very difficult to use FOIA to get information on somebody unless you obtain their permission, or they’ve died. Agencies tend to err on the side of caution when it comes to privacy, which is how you end up with situations where the Central Intelligence Agency and Federal Bureau of Investigation routinely redact the names and personal information from dead people. The US Marine Corps redacted Beyonce’s name from records related to her performance at the 2013 inauguration, despite the fact that the FOIA request was for explitely for records related to Beyonce’s performance at the 2013 inauguration.

USPS released Spanberger’s entire UPIS personnel file (far more than America Rising requested), without redactions is a pretty clear cut violation of the b(6) FOIA exemption.

Weirder still, the UPIS in particular has a reputation for over-extending privacy exemptions. Back in 2015, Joshua Eaton wrote about how his request for records originally released to the New York Times’ Ron Nixon was met with the infamous “neither confirm nor deny” FOIA response, better known as a “Glomar.” Why did the UPIS invoke a response more commonly associated with issues of national security? To protect Nixon’s privacy.

The security issue

A huge part of the reason why the this story has been getting so much traction is that an individual’s SF-86 is an extremely sensitive document. Nothing clamps up a FOIA request like a whiff of national security, and the CIA’s long-documented history of keeping even the most mundane of records under wraps for a half century or more is a testament to the deference shown by the disclosure process to what the state considers a secret.

SF-86 forms in particular have been under the spotlight: They were a major component of the announcement in 2015 of the breach of the Office of Personnel Management’s systems. That was likely the largest breach of US personnel data ever and prompted vows of retaliation from the Obama administration. The 127-page documents cover everything from medical and employment information to details on family members to psychological treatment.

While we certainly encourage some pushback against simply taking the agency’s word on what the public has a right to know, it is not up to debate what a Big Deal an unredacted classified document getting released through FOIA is.

What actually happened?

The short version? Somebody screwed up.

Yet more info about how America Rising got @SpanbergerVA07's SF-86. tl;dr NPRC (part of @USNatArchives) pulled the records in response to a FOIA req, then sent them directly to @USPS management, NOT FOIA office. That's NOT HOW IT'S SUPPOSED TO WORK. https://t.co/NCQlAAIXF0

— Natl Sec Counselors (@NatlSecCnslrs) August 29, 2018

And we mean really screwed up. Rather than going through the USPS’ FOIA office, the NPRC sent them to the agency’s HR office, which then stuck it in an envelope and mailed it to America Rising. That’s not how FOIA works.

However, the root cause for this debacle goes back even further - as FOIA lawyer Kel McClanahan writes in his piece for Just Security, the “original sin” of this request was NPRC even having Spanberger’s SF-86 in her personnel folder in the first place. As McClanahan explains, while those records were stored at the NPRC, they remain the property of OPM. And what does that mean?

This means that OPM rules apply to these records. And OPM rules state unequivocally that SF-86s are not to be filed in the Official Personnel Folder. This means that when the Postal Inspection Service put a copy of Spanberger’s SF-86 in her personnel folder, it violated OPM’s rules. Likewise, the NPRC would have violated OPM’s rules if it had added an SF-86 after it took possession of the folder when she left the Postal Inspection Service, since an Official Personnel Folder covers an entire federal career. So, first things first, the SF-86 should not have been there in the first place.

The USPS has since asked America Rising to return Spanberger’s file for proper FOIA processing, and in a public statement Thursday, the group agreed.

When this story first broke, the general consensus on the #FOIA hashtag was that at the very least somebody at USPS would be fired for this incident …

That person is almost definitely getting fired. https://t.co/z0moaO6GZl

— Bradley P. Moss (@BradMossEsq) August 29, 2018

if not arrested for violating - among many other laws - the Privacy Act.

However, as of today, the only discipline planned by the USPS is to hold additional FOIA training, an announcement that, to put it mildly, hasn’t gone over well in some circles.

Inexcusable of @USPS to simply conduct training to address this incredibly unacceptable & unlawful act to release @SpanbergerVA07's entire OPF & SF-86. Ppl should be disciplined for this egregious & incompetent human decision. @FOIA_Ombuds

— Mark S. Zaid (@MarkSZaidEsq) August 30, 2018

What’s the takeaway?

As it turns out, this is not a case of FOIA revealing more than it should have, but rather a cautionary tale of the reason FOIA has those safeguards in place - by bypassing the FOIA office, Spanberger’s file was not subject to proper review. If anybody at USPS FOIA office had actually gone near that request, they would have immediately recognized the giant flaming red flags sticking out of it, and redacted it into oblivion, if not just thrown the request out entirely.

Overall, we need more #FOIA rlses, not less. Hope this screwup isn't used as another disingenuous talking point in the push to roll back FOIA.

— NSA Nate (@NSANate) August 30, 2018

As McClanahan points out, this also explains why Spanberger’s own request for her file has been met with significant delays - it’s actually being processed through FOIA.

Now, mistakes are made, and occasionally a document is released without exemptions, or in one notable case, turns out to be the wrong record entirely. But in order to get this kind of cascading wave of failure, you need to have completely removed all of the protective barriers built into the law. As the National Security Archive’s Nate Jones notes, it’s important to frame this discussion as the exception that proves the rule (well, the law, really) - rather than an argument that there’s simply too much transparency going around.