There is no singular way that nonconsensual pornography ends up online. There have been a number of reports on revenge porn - a form of NCP in which intimate images are posted online by an ex-partner in an attempt to harm or harass - but other cases of NCP do not have a clear motive and are more difficult to discuss and to litigate - an estimated 79% of people who said they’ve uploaded NCP did so just to show friends, without intending to hurt the person in the photo. Nonetheless, victims of NCP, whatever the intent, suffer irreparable harm to their work, personal, and social lives.

Efforts to criminalize NCP have become debates over whether NCP restrictions violate First Amendment protections, often placing victims’ advocates and free speech groups on either side of the argument and playing out differently in different court districts.

Vermont and Texas, for example, both passed NCP laws in 2015, and this year, both states went to court over complaints that their NCP laws violated the First Amendment.

Both states’ laws classify the distribution of nonconsensual pornography as a misdemeanor, but the courts made two different rulings. In Vermont, the Supreme Court upheld the state’s NCP law, ruling that NCP is not protected speech. In Texas, the 12th Court of Appeals deemed the state’s NCP law as unconstitutional, stating that it violates the freedom of speech.

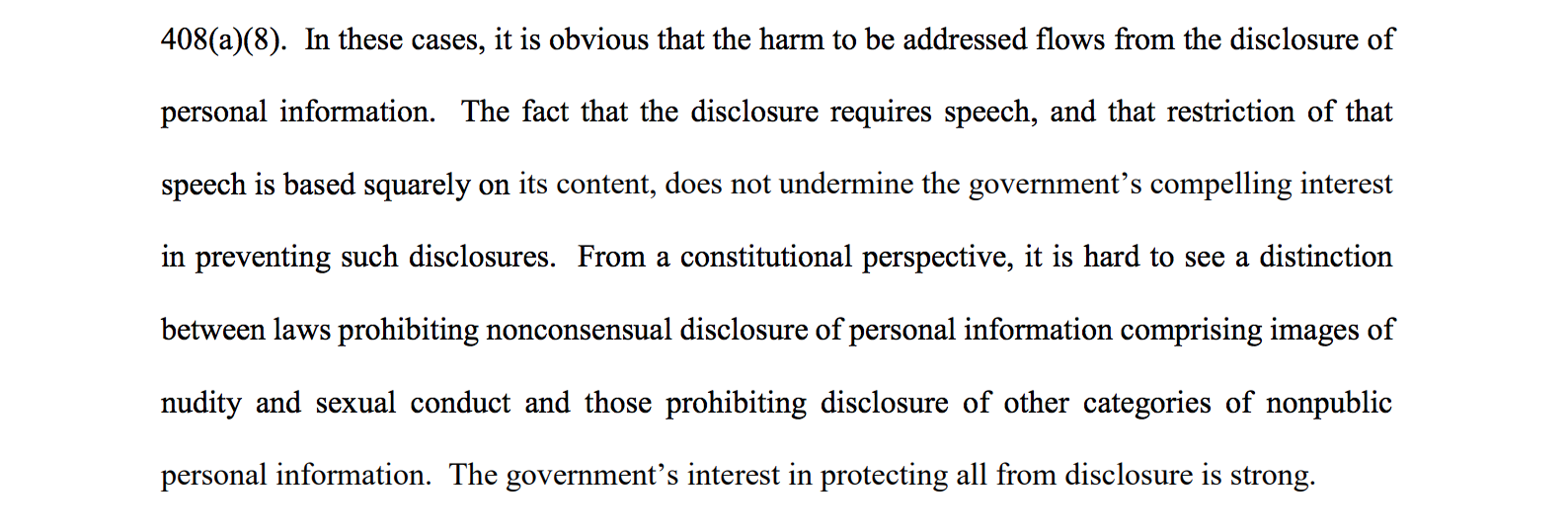

The Vermont Supreme Court ruled that the law was narrowly tailored to protect individuals’ rights to privacy while respecting the right to free speech. While the court refused to create a new category of unprotected speech, the justices cited other examples of personal information that cannot be disclosed without an individual’s consent, including a person’s medical history, social security number, and bank account information.

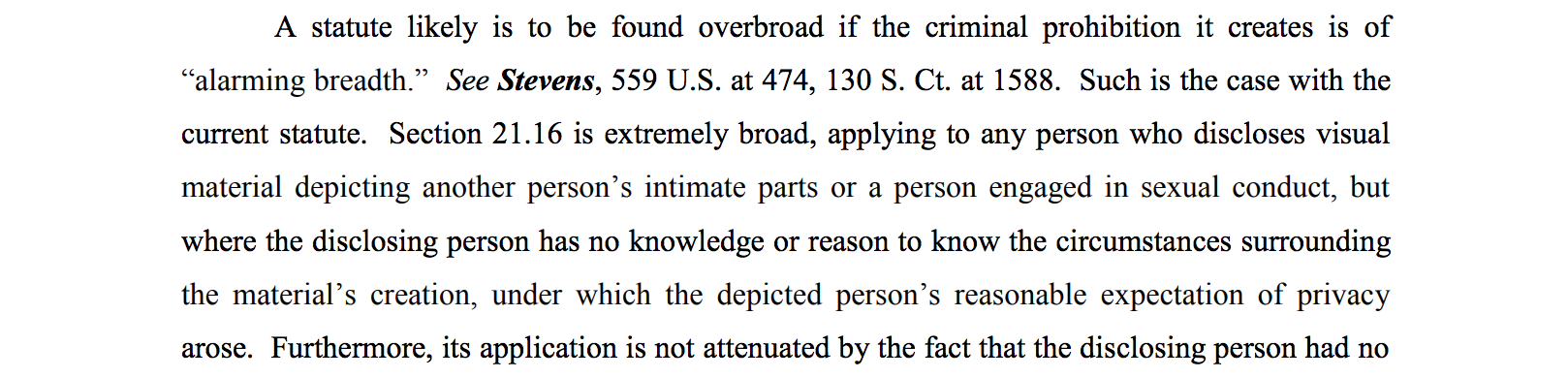

Meanwhile, in Texas, an appellate court ruled that Texas’ NCP law was too broad and violated the First Amendment of unwitting third-parties that disseminated NCP. The court wrote:

There are two differences between the Vermont law and the Texas law. In Vermont, the NCP law has an “intent to harm” clause. In Texas, the NCP law states only requires that the nonconsensual disclosure of private photos causes harm, but there is no explicit clause surrounding intent.

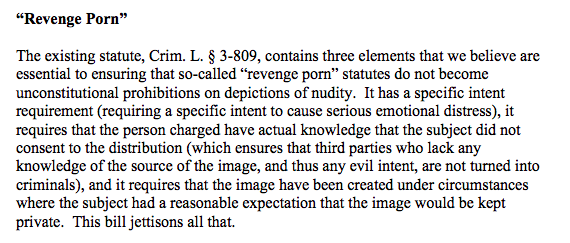

Among free speech advocates, the American Civil Liberties Union has been a particularly vocal opponent of proposed NCP laws nationwide. They’ve argued that NCP laws that not limited to cases of revenge pornography will be “overly broad” and chill free speech. In several states, the ACLU has rejected proposed NCP bills that they say would apply to images of public interest or would punish third parties that did not know the images were non-consensual, and they advocate for narrow definitions of revenge pornography (the ACLU use the terms “revenge pornography” and “NCP” interchangeably in their press releases) in state laws.

In Maryland, for instance, they articulated, in a written testimony opposing an amendment to the state’s NCP law, the positive elements in the existing legal definition of revenge porn:

Maryland is one state - along with Rhode Island, and Arizona - where the local ACLU chapter has opposed NCP laws that do not have explicit intent to harm clauses.

In 2014, the ACLU of Arizona filed a lawsuit against the state over its original NCP law and won. The law was criticized for not including a clause that specified the intent to harm. The law was modified to include an intent to harm clause in 2016. MuckRock reached out the ACLU of Arizona for comment, and a representative referred us to the ACLU’s national office, which has not yet responded to interview requests.

Senior staff attorney Lee Rowland, writing for the ACLU’s “Speak Freely” blog, acknowledged that revenge porn, regardless of intent, is harmful to victims, but said that, nonetheless, NCP laws cannot ignore constitutional obligations.

“[T]he Constitution means making tough calls sometimes,” she said. “That means opposing laws that chill or criminalize protected speech, even when we condemn the conduct that well-meaning legislators are trying to target.”

The intent to harm, however, is difficult to prove and sometimes absent from the perpetrator’s reasoning. Katelyn Bowden is the co-founder of the BADASS Army, an advocacy group and community for victims of non-consensual pornography, and she’s seen firsthand just how hard it is to provide evidence of intent. Herself a victim of NCP, she said intent clauses make laws nearly unenforceable. One alternative to these clauses could be to prosecute uploaders for disclosing images despite a “reasonable expectation of privacy.” Illinois has this type of clause written in their penal code.

In Bowden’s case, nude photos were uploaded online by a man who had stolen her ex-partner’s phone, which contained the intimate pictures. The man had no excuse for the act or a clear intent to harm, and he confessed to posting her images to xHamster. She took her case to the police; they told her that there was nothing they could do. In Bowden’s state of Ohio, there are no explicit laws criminalizing non-consensual pornography.

Bowden said she is a strong proponent of the First Amendment but that it does not give people the right to hurt others or ruin lives.

“Freedom of speech is your ability to say you don’t like the president or to argue an unpopular opinion,” she said, “It does not give you an excuse to harm another person.”

Nonetheless, laws and law enforcement do little to address the harm done to victims. Galen Hair, partner at Scott, Vicknair, Hair & Checki, LLC, is one of the volunteer pro or low bono attorneys at the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative. He says that there is a stigma surrounding people who take intimate photos of themselves, especially in law enforcement. Every NCP case is different, and explicit laws often do not fit into every victim’s situation. Hair says that he employs different legal tactics depending on the circumstances of the case. Some include the use of copyright law, invasion of privacy and false light torts, and domestic abuse law.

“These cases are highly human relationship based,” Hair said, “The first analysis has to be who is the person sitting in front of me and what is their relationship to the person that messed up.”

The conflict between right to privacy and right to free speech continues to be an issue surrounding the creation and enforcement of non-consensual pornography laws. There is no federal standard for prosecuting NCP. Senator Kamala Harris’ (D - CA) ENOUGH Act has not moved through Congress; as of November 2017, the act was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary, but no further action has been taken.

Without federal guidance, individual states must continue to determine how to handle cases of NCP while fulfilling their obligations to both private individuals and the First Amendment.

Image via Pexels