Public records advocates have always fought for stronger laws that allow for better oversight and accountability. Despite these efforts, law enforcement agencies are still finding loopholes to allow for the retention of information. While new police transparency bills in California and a recent public records overhaul in Massachusetts are huge victories for access, requesters still face serious barriers when trying to peek past the thin blue line.

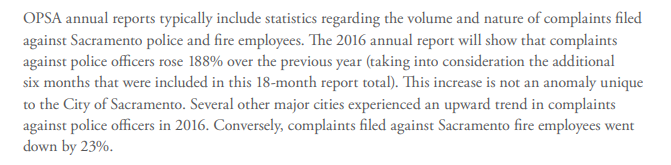

In 2016, Sacramento Police took two months to release body camera footage of the killing of 50-year-old Joseph Mann. Police say Mann was walking down the street waving a four-inch knife and threatening officers before 18 shots were fired at him. Following the death of Mann, outraged community members rallied together demanding a revision into the SPD’s use of force policies. According to the City’s Office of Public Safety Accountability 2016 Report, complaints against police officers rose 188% over the previous year.

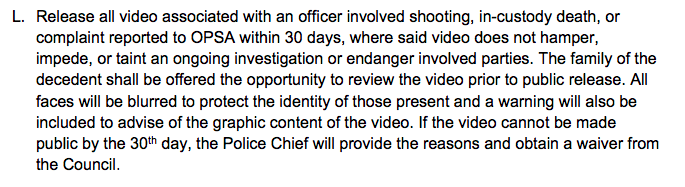

Following public outcry, Sacramento ordered a review of current law enforcement policies, which later resulted in a batch of new reforms, among them changes to body camera practices. A landmark ordinance was passed, which includes the 30-day release of body-camera footage but allows families to view the footage before it is publicly released.

On a statewide level, Sacramento’s 2016 ordinance was a huge step forward for transparency in law enforcement. California’s privacy laws had remained more or less untouched for decades, until this year, when Governor Brown signed into law two new laws specifically aimed at unlocking records of internal investigations and body camera footage. SB-1421 and AB-748 give the public an opportunity to review records that were once exempt from oversight.

“Too often family members, under the old California law, aren’t told what happened to their loved one and they have to file a lawsuit to even figure out basic information like why their loved one was killed,” said ACLU Southern California’s Director of Police Practices and Senior Staff Attorney, Peter Bibring.

Still, many say the state continues to hold among the most restrictive policies when it comes to the release of police records. Legal Counsel for the California News Publishers Association, Nikki Moore, says that California is home to one of the strongest secrecy laws in the nation.

“The law says that [police departments] have to give arrest information and that’s it. It gives police the ability to say no to a lot of things,” said Moore. “There are just multiple layers of secrecy, and we have tried at the CNPA to change those rules. Not only has legislation failed, but the court consistently interpreted the law to be limiting of access.”

However, there is hope that new laws like SB-1421 and AB-748 are paving the way for a broader reform of police accountability and access to public records.

“Now, we have changed the investigatory records exemptions by saying that at some point, if you have a critical incident, then we have a public right to access that information pretty quickly,” said Moore. “Implementation is everything. That’s why the law was drafted, so it can be enforced by the people.”

With the tides changing in California, it’s yet to be seen just how new law enforcement laws will help bridge the gap between police departments and the community; records requesters themselves have to take on the task of enforcing the new laws and ensuring police departments are properly applying the law.

Across the country in Massachusetts, transparency advocates are less optimistic - and many say that law enforcement agencies are one of the biggest culprits in blocking access to records in the state.

“It is extraordinarily frustrating,” said Todd Wallack, data journalist and investigative reporter for the Boston Globe, .

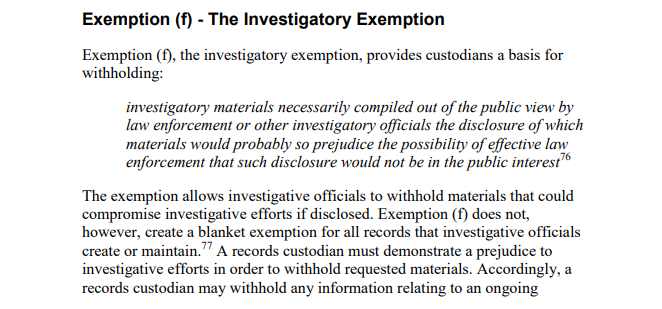

In 2016, Massachusetts revised its public records law, which similar to California, was the first major change to the law in over 40 years. Although the state is still working on bringing body camera practices to its police departments, the investigatory exemption, exemption (f), makes accessing investigative records challenging, if not impossible, even in cases that have been long closed.

Worse yet, exemption (f) is too often applied in situations that stretch the definition of “investigatory.” Earlier this year, Wallack requested photos of an officer and detective but was faced with the investigatory exemption, which the department said was necessary because the two were working on investigations.

In the end, the request was appealed and Wallack won the records. However, the appeals system in Massachusetts is lackluster at best, and, at the very least, can take weeks, if not months, to process the request.

“In Massachusetts, even if the investigation is completed [police departments] will use [exemption (f)] to not release the information,” Wallack said. “They will argue that while someone is being prosecuted, records need to be withheld because it might taint the jury’s outlook on the case.”

Wallack added that the Globe has tried to obtain records on Aaron Hernandez from the Bristol County District Attorney’s office. Hernandez was a former New England Patriots’ player who committed suicide in prison after a jury convicted him of murder.

“The Bristol County District Attorney’s office is refusing to release records on Aaron Hernandez arguing that it could jeopardize prosecution. But Aaron Hernandez is dead,” said Wallack.

Even if the request doesn’t involve an investigation, police departments will often cite Exemption (c), the privacy exemption, as a broad means of denying the release of information that could “jeopardize public safety.”

In November, the Massachusetts State Police Department cited a decision from a 1976 case to withhold records the department deemed too sensitive.

Bougas v. Chief of Police of Lexington was a case held in Massachusetts Supreme Court in 1976 to deal with exemptions of criminal investigation records.

Beyond California and Massachusetts, keeping police accountable appears to be a nationwide problem.

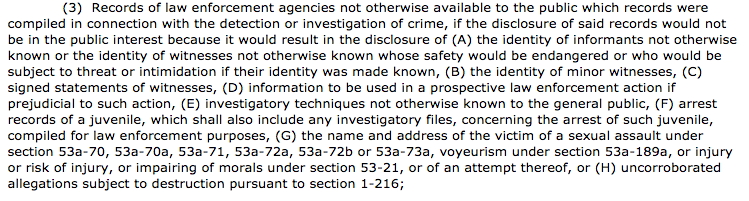

In Iowa, law enforcement agencies are citing exemptions with broad interpretations. Agencies in the state have said that any record that is part of their investigative file should be considered confidential forever, citing Iowa Code 22.7, which lays out confidential records exempt from Iowa Open Records Law.

Such was the case with Iowa resident Monica Speaks, who in 2016, was seeking records of her father’s 30-year-old death records. The Iowa Department of Public Safety provided her a brief overview of the records but refused to release them in its entirety. That same year the Des Moines Register reported the DPS’ refusal of all or parts of 40 out of 59 records requests the Department received within the first six months.

Similarly, Tennessee NewsChannel 5 filed a request for former Director of the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation’s phone log, travel summaries, and credit card purchases. The request was rejected on the grounds that the documents were now part of an “ongoing investigative file,” despite the fact that the request was sent to individual state departments and not the state’s District Attorney’s office.

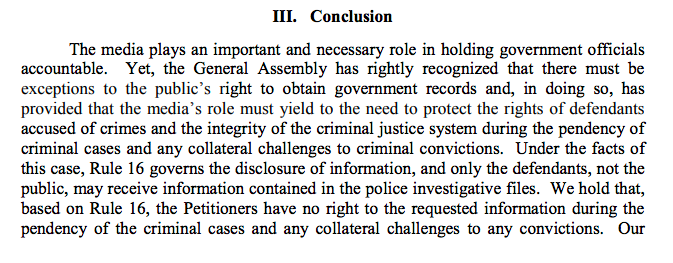

The news organization sued and ultimately lost in court. The ruling Judge concluded that there were “exceptions to the public’s right to obtain government records” and the documents could not be released as they were part of a police investigative file.

There are some exceptions. Connecticut is noteworthy for having a good public records law as it only holds 28 exemptions.

“We don’t have that many exemptions and at the end of the day, police record exemptions are pretty good, not half bad,” said Legal Director for ACLU Connecticut, Dan Barrett.

But the state still holds certain provisions on what investigative records can be released.

Florida is also hailed as one of the best states to provide access to records. The state’s Sunshine Laws are embedded in their constitution and asking for booking records and crime reports is generally simple.

“It’s easy to get police reports, and law enforcement records law is one of the oldest and one of the strongest in the nation,” said President of the First Amendment Foundation Barbara Peterson.

Still, Florida Sunshine Laws hold over 1,000 exemptions, each blocking a specific set of records. Sunshine Laws do favor requester access to investigative records made or received by public agencies.

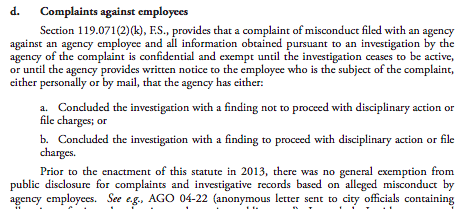

But they block access to employee misconduct investigations until the investigation is closed or makes contact with the employee in question.

“Police agencies have all the cards, they hold all the footage, and they want to assert other provisions of the law,” added Moore. “News organizations have been pretty aggressive in trying to access police records, but we haven’t really seen a ton of enforcement because the laws haven’t shifted. But maybe people and organizations have to call out [police department’s] bluff.”

With a greater need to hold law enforcement agencies accountable, requesters have a responsibility to learn the law and know when to enforce their rights. Broad interpretations of the law continue to hinder access into government practices, but records advocates say that when the absence of the law prevails, learn how to work your way around exemptions.

“Transparency only wins when agencies decide to release information,” Moore said. “But you do need requesters, whether media, or the ACLU, or a family trying to get information. All these people have a right to enforce the law and mandate disclosure.”

Image via Wikimedia Commons