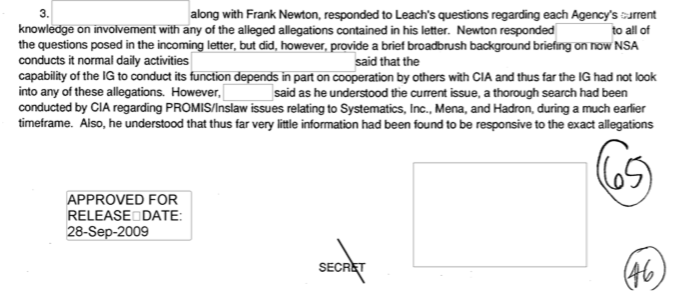

The investigations into the Inslaw affair were the result in the Department of Justice, the Central Intelligence Agency and National Security Agency all responding to allegations involving the PROMIS software. Each agency denied their involvement and any wrongdoing, to varying degrees of credibility. The investigations eventually involved Inspectors General, a Special Counsel, and Congressional briefings, only scarce details of which have been released more than 20 years later. The NSA performed what it considered a very thorough search that proved that its PROMIS software was wholly separate from Inslaw’s. While the review of said software was thorough, the search nevertheless failed to identify the Agency’s purchase and use of at least one other piece of software called PROMIS.

Nearly two years after the FOIA request was submitted, and approximately eight years since a parallel request was filed by one of the founders of Inslaw, the NSA responded with an interim release of documents, often redacting information which was already public. In an oddly related FOIA gaffe, the NSA also directed the author’s attention to three documents already available online. Of these, one was a press release from the DOJ announcing it had found it was innocent, with the other two being the DOJ reports the press release was based upon, both of which had been uploaded by the author rather than the government. The NSA’s pointed awareness of these documents is significant, in that their redaction decisions ignored what was already declassified and officially acknowledged. In many places, the Agency redacts names and specific details from the draft report, that are included in the final report with only minor rephrasings.

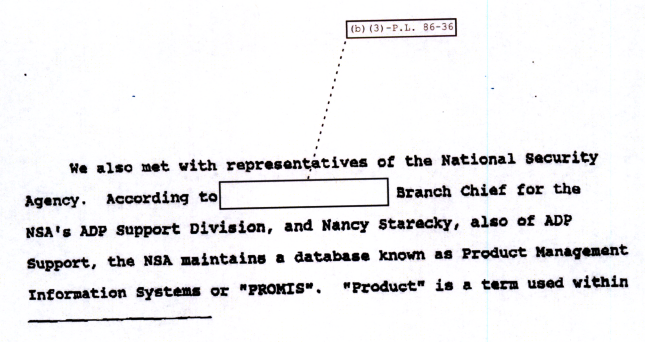

The NSA’s release, more than 20 years after the DOJ report was published, redacts the name of the long acknowledged branch chief: Carol Fay Boomer.

The documents, along with a separate release specifically focused on NSA’s PROMIS, are evidence that their main database predated the PROMIS scandal by nearly a decade. These documents, some of which detail NSA’s earliest databases for collecting SIGINT data and making it available on government networks, prove that they had PROMIS software independent of Inslaw’s to an almost comical degree. However, the documents also highlight two significant problems that often arises in these types of investigations. The first is that the government’s bias and desire to clear itself can undermine the results of the investigation, and the public’s faith in them. The second problem, which arises from the first, is that it indirectly encourages a culture of suspicion and occasionally outright conspiratorial thinking.

After four years of searching for records related to PROMIS and the NSA’s use of it, it had apparently focused solely on their SIGINT database. It wasn’t until mid-July 1996 that the NSA identified their 1986 purchase and use of a piece of software called PROMIS. This discovery wasn’t prompted by the NSA’s own search or self-awareness, but by an old newspaper article which was provided to the DOJ, and subsequently the NSA. According to the article, NSA had purchased software called PROMIS “from a company called Promis Systems Corporation, a division of I.P. Sharpe.”

The ensuing search mirrored the exhaustive search into the PROMIS database collecting NSA’s SIGINT information. It similarly documented that the software was used to track products in an NSA fabrication facility which was discontinued when National Semiconductor Corporation took over the contract, using their own facility and discontinuing the NSA’s use of Sharpe’s PROMIS.

While it was distinct from Inslaw’s PROMIS, the software associated with the manufacture of the chips shouldn’t have escaped NSA’s research and investigation. Some of the PROMIS related accusations involved modifying the circuits of computers in various ways that would allow either backdoor access or remotely reading information, even from air-gapped machines. This makes any connection between PROMIS and the manufacture of circuitry relevant to the investigation, even if only to quickly clear and distinguish Sharpe’s PROMIS from both NSA’s PROMIS and Inslaw’s PROMIS. That it took four years and outside intervention to prompt NSA to apparently discover its use of Sharpe’s PROMIS casts serious doubt on the thoroughness of their inquiry, which increasingly looks like it was a mile deep but an inch wide – digging thoroughly into one specific thing which they already knew the answer to, without looking at anything else.

This, combined with similar instances such as the CIA’s failure to disclose their having been offered a copy of Inslaw’s PROMIS, do considerable damage to the credibility of the government in its various denials. By having to constantly return to the question, and confess that they had missed or withheld something, it becomes more difficult to accept the final results of their inquiries. As a result, even if the full truth were ever revealed, it is unlikely that it would be completely expected. Through their repeated failures to disclosure information, various government agencies have trained members of the public to engage in suspicious and conspiratorial thinking that leaves them vulnerable to the liars and con artists who inevitably (and for varying reasons) try to inflate every scandal, making actual justice and accountability that much more difficult.

Additional documents from the release are pending, though at least one document (ostensibly documenting the government’s innocence) has been withheld “because its disclosure could be reasonably expected to cause serious damage to national security.” You can read the most recent release embedded below, and the rest of MuckRock’s coverage of the affair here.

Image via Wikimedia Commons