An examination of the original handwritten police notes about the death of journalist Danny Casolaro contradict the official claims and conclusions of the Justice Department and the Special Counsel investigation led by Judge John Bua. The police notes, originally seized by the federal government and allegedly still under seal, undermine the narrative that Danny Casolaro committed suicide, and appear to provide corroboration that someone took his briefcase containing many of his notes and papers at the time of his death.

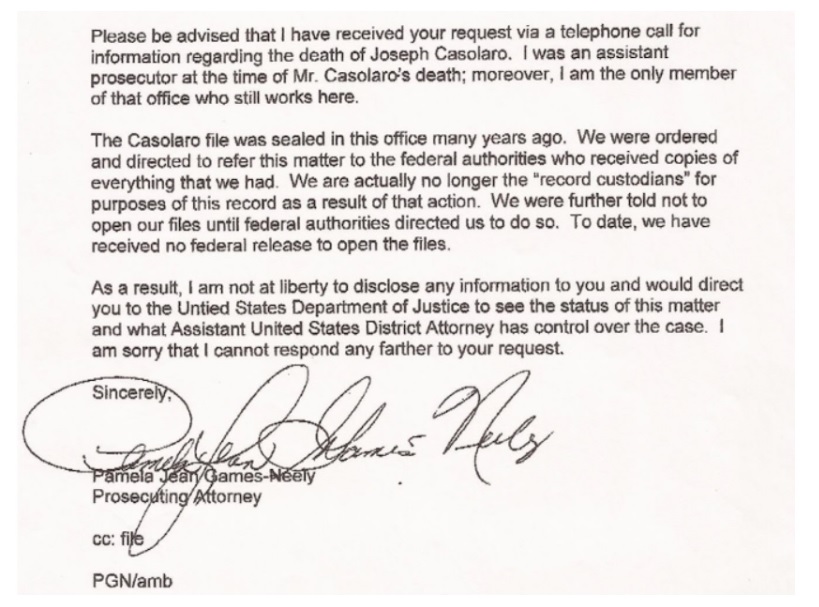

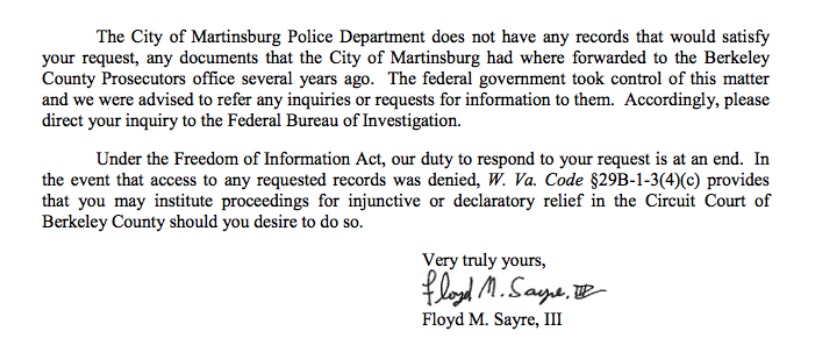

MuckRock previously filed a FOIA request with Martinsburg Police Department for records relating to the death of Danny Casolaro, including notes, photographs and autopsy reports. A response dated ten days later, but not received until nine months later (the statutory time limit is five business days), denied the request by referring to the federal government seizing jurisdiction and custody of all documents. This is consistent with previous reports from the Berkeley County Prosecutor’s office that the materials were sealed. Although the records still being apparently sealed, copies were obtained through a combination of Special Access Reviews, visits to different archives, and the cooperation of a number of people who were involved in the case.

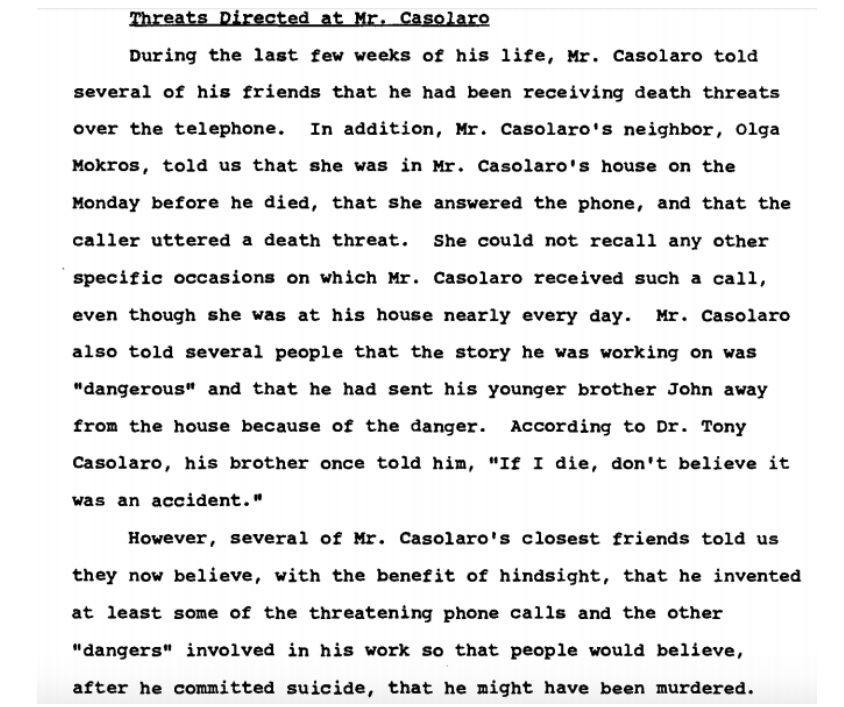

In some instances, the Bua Report simply seems to leave out relevant information. One passage in the Bua Report describing threats against Casolaro, for instance, completely misstates the facts as presented in the original police notes. The Bua Report then contends that Casolaro fabricated the death threats while planning to commit suicide because he wanted to make people think he was murdered.

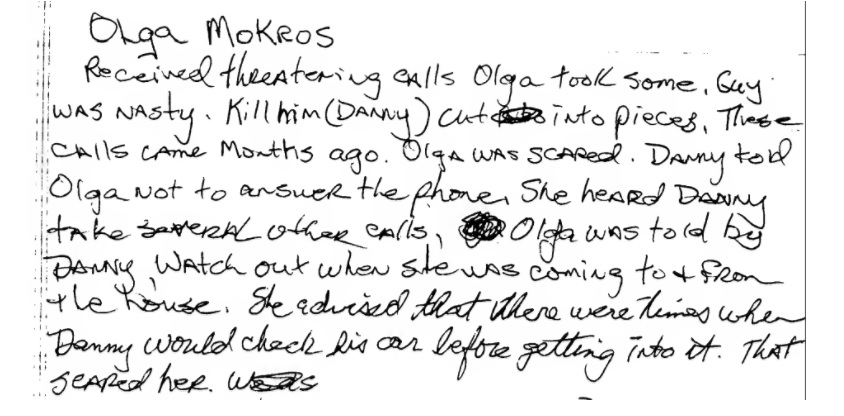

This contention is not only unsupported by the original documentation, it’s contradicted by it. According to the Bua Report, Casolaro began reporting death threats “during the last few weeks of his life,” with only a single report of a death threat being offered by Olga Mokros the Monday before his death. According to the Bua Report, “She could not recall any other specific occasions on which Mr. Casolaro received such a call, even though she was at his house nearly every day.” This statement is directly contradicted by the notes of the police interview with her, in which she said that she had answered the Casolaro phone to hear threats to kill Danny and “cut him into pieces.” According to the notes, this was “months” before his death.

The notes go on to describe a death threat against Danny that she received around the time of his death, which may be the same call described in the Bua Report. It’s not immediately clear if the false statement in the Bua Report is the result of a deliberate decision to ignore the police notes, or if the Special Counsel was denied access to them or not properly informed of their contents.

If this were the only error, or even the worst error, it might do little to undermine the Bua Report’s conclusions regarding Casolaro’s death. It is neither.

Arguably the worst error in the Bua Report is in their response to the question of Casolaro’s missing briefcase, which they concluded didn’t exist. According to the Bua Report, only one witness - a front desk employee at the hotel - thought they might have seen the briefcase. The Bua Report incorrectly claimed that “no other hotel employee recalled seeing Mr. Casolaro with a briefcase.”

Elsewhere, the Bua Report twice describes Lopez as having been “not sure” and decide that since “none of the other hotel employees recall seeing a briefcase or documents … Lopez was probably mistaken.” The conclusion that the briefcase didn’t exist is then used to undermine the statement from William Turner that he had just returned documents to Casolaro, documents which may have related to Alan Standorf, an alleged NSA whistleblower who was murdered and whose records are still withheld by the FBI due to an unidentified 25+ year old pending law enforcement proceeding.

Contrary to the assertions of the Special Counsel’s office in the Bua Report, the original police notes show that there was a second witness at the hotel who saw the briefcase: Barbara Bettinger. According to her statement to the police, Bettinger had seen the briefcase. The Bua Report describes Bettinger as an employee at the hotel, while failing to describe her telling the police she had seen Casolaro’s briefcase.

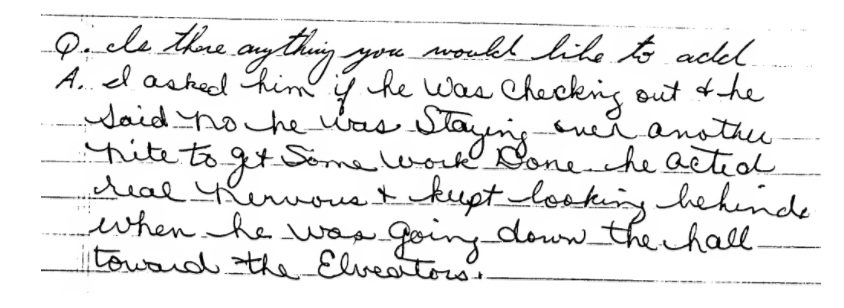

According to the handwritten police notes, Bettinger saw Casolaro on the afternoon before his death, while standing in the doorway to his room. She noted that he seemed nervous and kept looking over his shoulders.

According to the Bua Report, Bettinger was the last hotel employee to see Casolaro alive when she spoke with him that Friday afternoon.

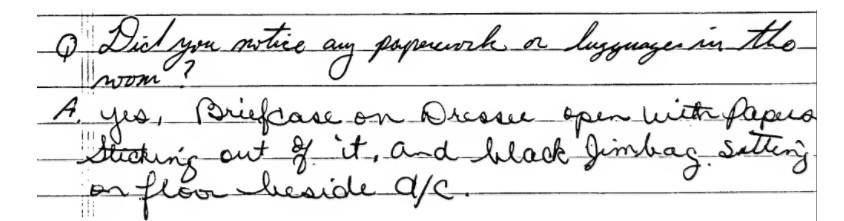

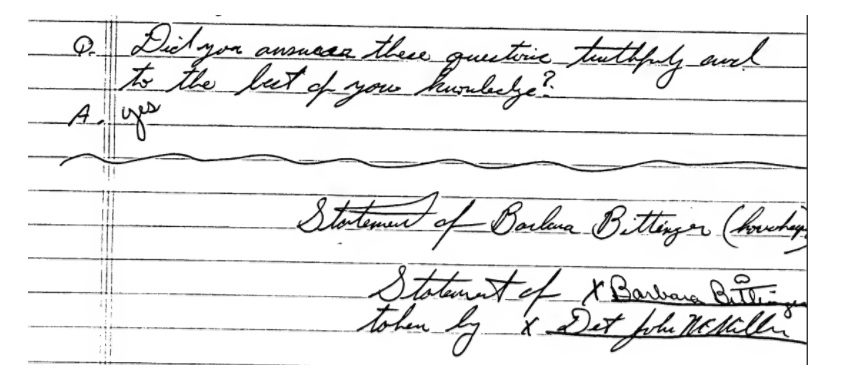

Most relevantly, Detective John McMillen asked Bettinger “did you notice any paperwork or baggage in the room?” She answered that “yes,” there had been a “briefcase on [the] dresser, open with papers sticking out of it.” She saw the papers on the same afternoon Turner alleges he return papers to Casolaro, though the Bua Report points to inconsistencies in Turner’s retellings of this.

Bettinger signed the notes, affirming their accuracy.

As both the handwritten police notes and the Bua Report note, the police didn’t find Casolaro’s briefcase or papers, which he still had with him in his hotel room the afternoon before he died. Their disappearance means that Casolaro either had at least one unknown interaction with someone or the papers were stolen from his room after his death.

The disappearance of the papers does more than confirm the existence of an unknown player in the final hours, if not the final moments or immediate post-mortem, of Casolaro; they also provide a potential motive for his death: the removal of evidence. The most likely candidate for this unknown player is the deceased Joseph Cuellar, who had not only reportedly threatened Casolaro, but provided contradictory alibis for Casolaro’s death.

As the Bua Report notes, Cuellar had reportedly threatened both Lynn Knowles, an ex-girlfriend, and Casolaro. At the same time, Cuellar referenced Anson Ng, a Financial Times reporter who had been killed in Guatemala and was reportedly looking into aspects of the Inslaw affair. Cuellar denied this, though Knowles continues to stand by her statements. Bua cleared Cuellar of wrongdoing, asserting that witnesses placed him in Washington D.C. on the day Casolaro died, processing out from Desert Storm and into Southern Command.

The Bua Report’s reliance on these witnesses ignores the fact that Casolaro’s estimated time of death was between 7 and 8 AM in Martinsburg, West Virginia - a two hour drive from Washington D.C., which could have given Cuellar time to return before witnesses apparently saw him in D.C.

The Bua Report’s dismissal of Cuellar as a suspect ignores his contradictory alibis. According to a DOJ memo written to the Assistant U.S. Attorney, “Cuellar advised that three (3) to four (4) weeks prior to Casolaro’s death, he left for Panama and was advised of Casolaro’s death through a phone call to Lynn Knowles. Cuellar returned from Panama to attend Casolaro’s funeral.” If Cuellar had left for Panama at that time, he would have already been processed into Southern Command and wouldn’t have returned to Washington D.C. to process out of Desert Storm (nowhere near Panama) and into Southern Command (which did have jurisdiction over operations in and around Panama).

The two alibis are impossible to reconcile. To date, there is no evidence that the DOJ ever investigated the change in Cuellar’s alibi, nor was it publicly reported on. The documentation was only obtained relatively recently as part of a Special Access Review with the National Archives.

Combined with other instances in which the Special Counsel ignored or was left ignorant of relevant information about the Inslaw affair and he PROMIS scandal, these omissions and distortions raise additional questions about the integrity of the Bua Report and its conclusions, which have now been challenged on both the death of Casolaro and on the PROMIS scandal.

As of this writing, over 20,000 pages at the National Archives on Casolaro’s death, the PROMIS scandal and the investigations into the Inslaw affair remain inaccessible to the public. While the Special Access Review for all the documents continues, you can file a FOIA request for individual sections to prompt a speedier release to the public. Previously released sections can be found here. You can read the rejection from Martinsburg PD on the request page, or you can read their separately obtained handwritten notes below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via People of the Black Circle