In June 1956, Lyndon B. Johnson caused a “hullabaloo” over the search search of a Senator’s office conducted by Department of Defense security officers who were looking for a potential listening device. Johnson caused such a stink that the Federal Bureau of Investigation decided to avoid helping the Senate with security issues lest they be subject to unnecessary scandal the way the DOD security officers were.

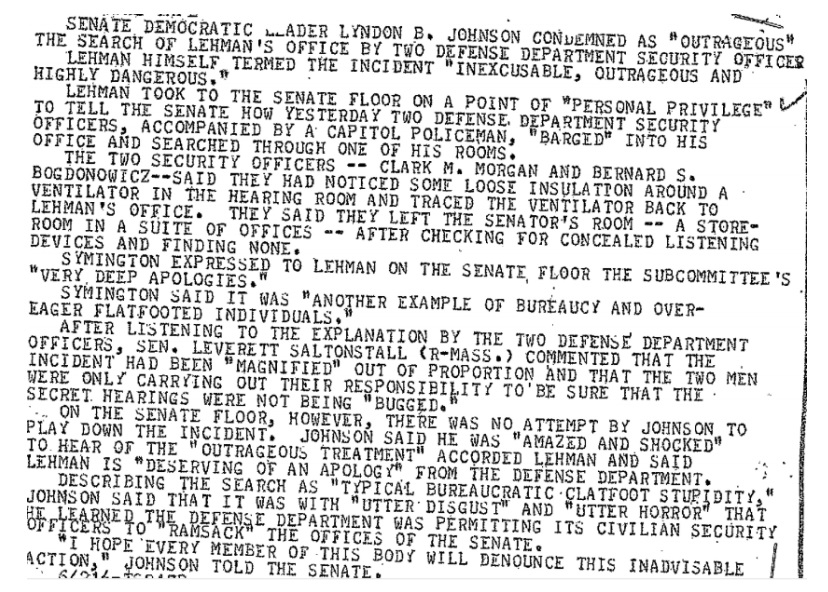

The incident arose after two DOD security officers noticed loose insulation around a vent in a Senate hearing room. The security officers traced the vent to a storage room in Senator Herbert Lehman’s office, which they proceeded to search along with a member of the Capitol Police. Lehman called the incident “inexcusable, outrageous, and highly dangerous,” with Senator Stuart Symington calling it “another example of bureaucracy and overager flatfooted individuals.” Senator Leverett Saltonstall defended the security officers, noting the incident was being blown out of proportion. In response, Johnson called the matter “outrageous” and “typical bureaucratic flatfoot stupidity.” Johnson reportedly reacted with “utter disgust” and “utter horror,” calling on the rest of the Senate to denounce the search.

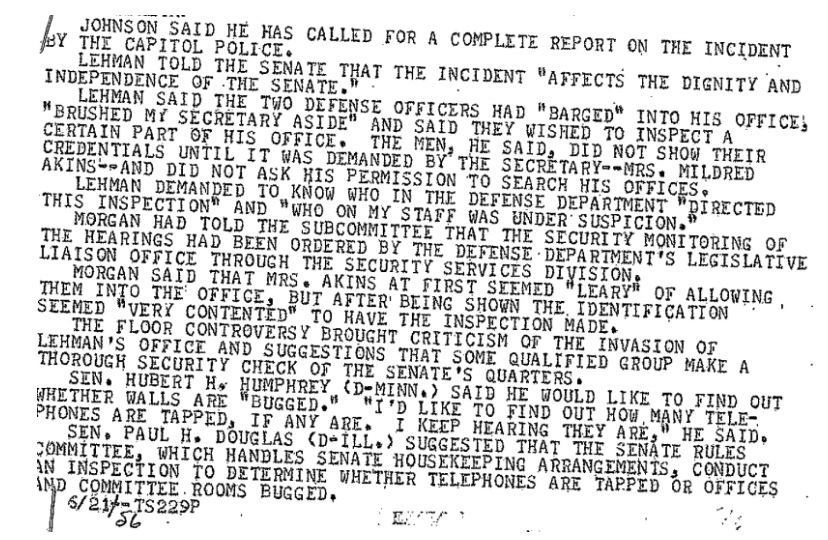

Johnson went on to call for a report on the matter from the Capitol Police, with Lehman arguing that the incident somehow affected “the dignity and independence of the Senate,” seemingly because of their brusque manner. Senators Hubert Humphrey and Paul Douglas called for a search of the Senate and rules governing such matters, respectively.

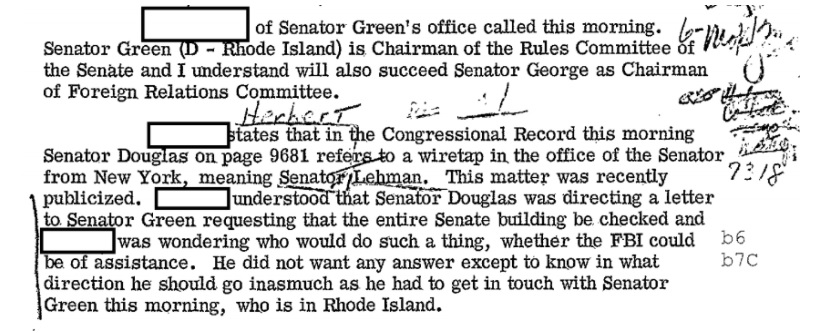

According to an FBI memo written the next day, Douglas was sending a letter to Senator Theodore Green, the Chairman of the Senate Rules Committee, “requesting that the entire Senate building be checked.” Green’s staff, in turn, reached out to the Bureau to inquire if they could be of any assistance, or where else the Senator’s office should address their inquiry.

The memo appears to briefly lament the Bureau’s inability to simply refer the matter to a commercial contractor.

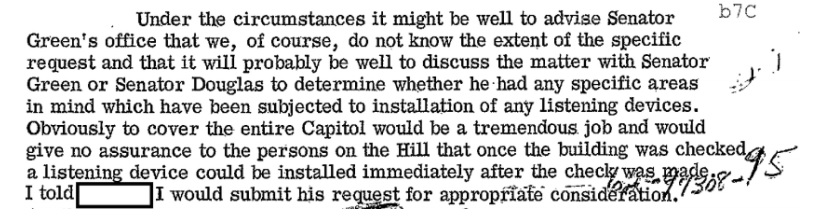

The memo reasonably points out that they would need to know the specifics because they could calculate a response to the request, and that covering “the entire Capitol would be a tremendous job.” Less reasonably, the memo seems to argue against checking for existing listening devices by pointing out that a device could be planted after they perform the check.

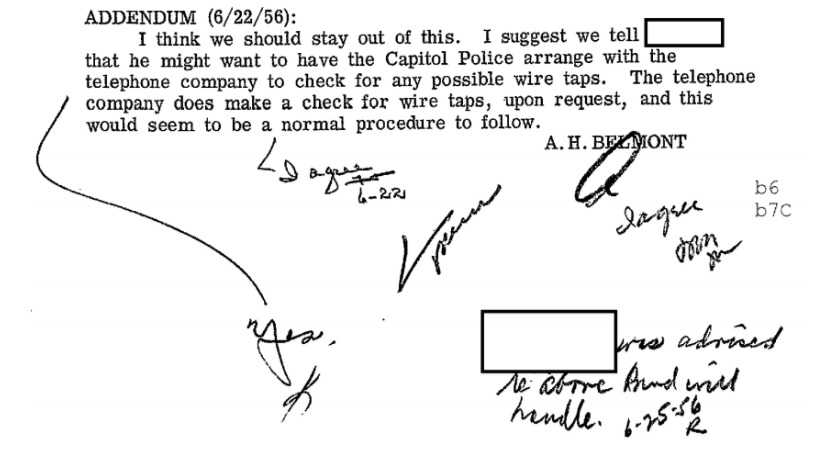

An addendum to the memo argues that the Bureau should stay out of the matter, and tell the Senator’s office that they should have the Capitol Police arrange for a check with the telephone company.

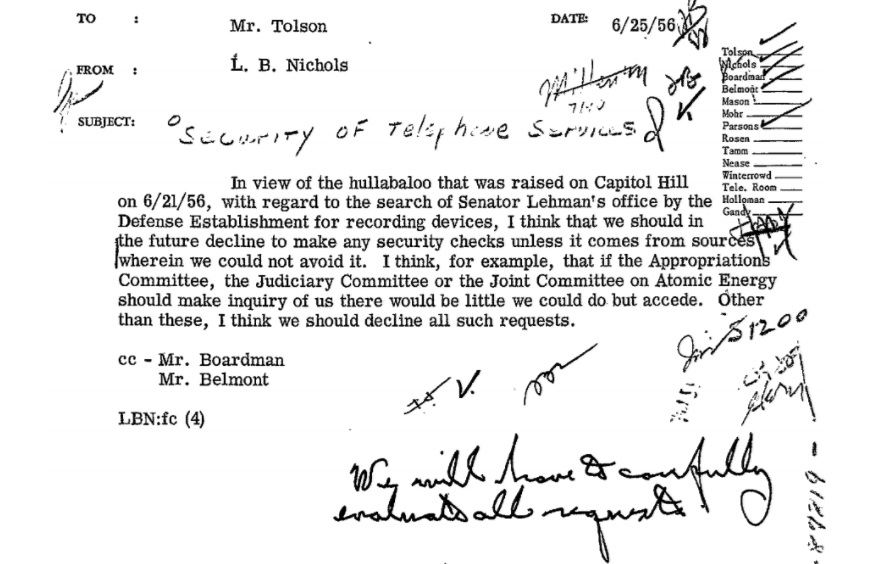

Another memo, written three days later, similarly recommends that the Bureau avoid the matter. Assistant FBI Director Louis Nichols cited “the hullabaloo that was raised on Capitol Hill” as reason to “decline to make any security checks” for the Senate “unless it comes from sources wherein we could not avoid it.” A handwritten note below the memo seems to agree, noting that the Bureau would “have to carefully evaluate all requests.”

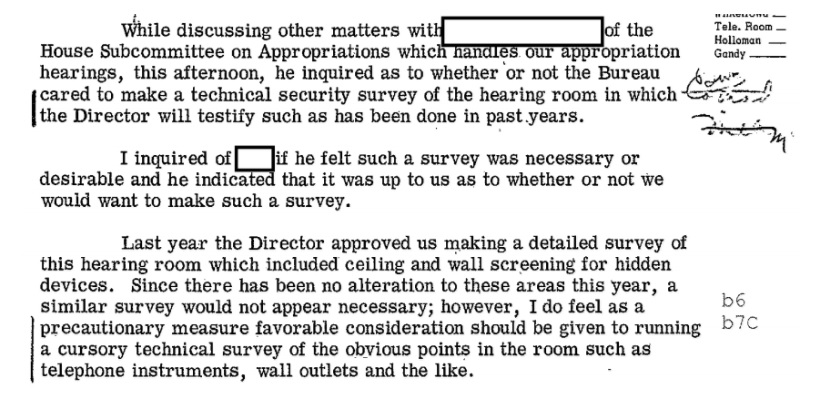

According to the memo, one such unavoidable source was the Appropriations Committee. While it’s not immediately unclear from the file if the Bureau actually refused any offers, it does appear that they complied with them from the Appropriations Committee. In the following January, the Appropriations Committee requested the Bureau perform a sweep similar to the ones they had done in the previous years. Citing a lack of structural changes to the hearing room in the past year, the Bureau felt that it wasn’t necessary to perform a detailed survey - but that “a cursory technical survey of the obvious points in the room” should be given “favorable consideration” as a precautionary matter.

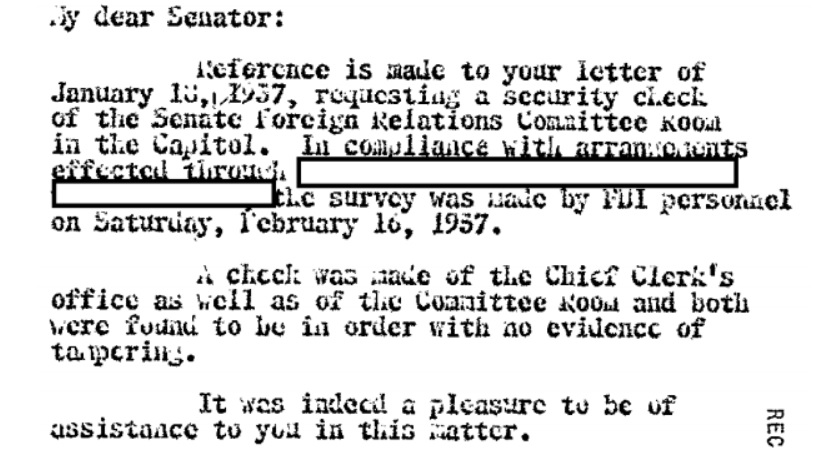

At least one search for a committee not suggested as an exception was conducted soon after - the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. In response to a request from Green, the Bureau conducted a search of both the Committee Room and the Chief Clerk’s office.

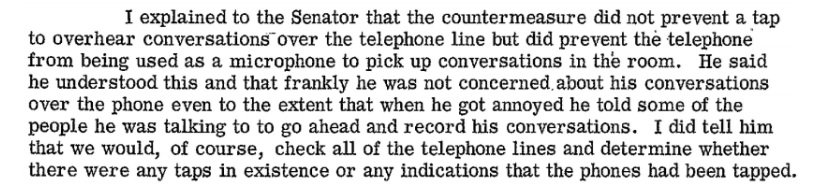

One memo noted that the Bureau limited the search to “the most likely places,” while another noted the Bureau explained the limits of the search to the Senator. While just a few years prior, the FBI and the phone company had decided to withhold the ability to use inactive phones as listening devices from the White House, the Bureau now readily admitted to Green that this was possible, but that the countermeasures the Bureau had installed would prevent it from happening to his phones. This was apparently the Senator’s main issue, as he was so unconcerned with his phone conversations being listened to that he would, out of annoyance, tell others “to go ahead and record his conversations.”

While it’s unclear just how damaging LBJ’s “hullabaloo” was to the Senate’s relationship with the Bureau, it’s interesting that the ruckus he caused, along with Lehman and Symington, was enough to have the Bureau reconsider whether to comply with truly optional Senate security requests, or to pass the buck to another jurisdiction - that of the Capitol Police. While the Capitol Police are immune to FOIA, the Bureau isn’t and a new request has been filed with them to learn more about the relationship between the two agencies. In the meantime, you can read the relevant portion of the file below.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Wikimedia Commons