While the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s track record with FOIA has never been good, it’s hard not to argue that it has recently gotten exponentially worse. In just the last few years, the Bureau has thrown out thousands of FOIA requests because there were too “burdensome,” investigated FOIA requesters, redacted the names of fictional characters and engaged in questionable fees practices. Most recently, the FBI has declared that - contrary to all statute and case law - the dead have an expectation of privacy.

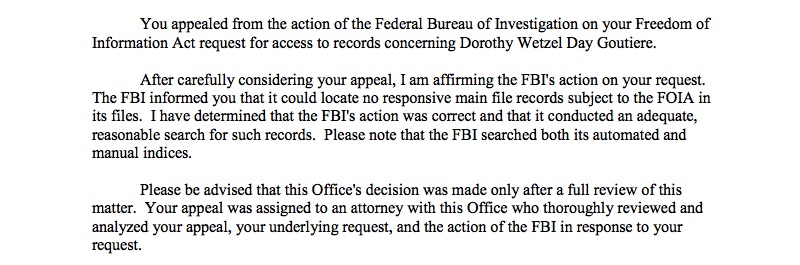

Beginning with a FOIA request filed by MuckRock in December 2015 for the file of Dorothy Hunt, the wife of Watergate planner Howard Hunt who died in a plane crash while under mysterious circumstances in the aftermath of the break-in, the FBI has responded to requests for information on Dorothy Hunt in ways that raise the question of whether the Bureau is incompetent, acting in bad faith, or both. Three months after the initial request, the Bureau responded by falsely declaring that no records existed or could be found. When the matter was appealed, the Department of Justice upheld the FBI’s finding and said that the search was reasonably conducted and there were no responsive records.

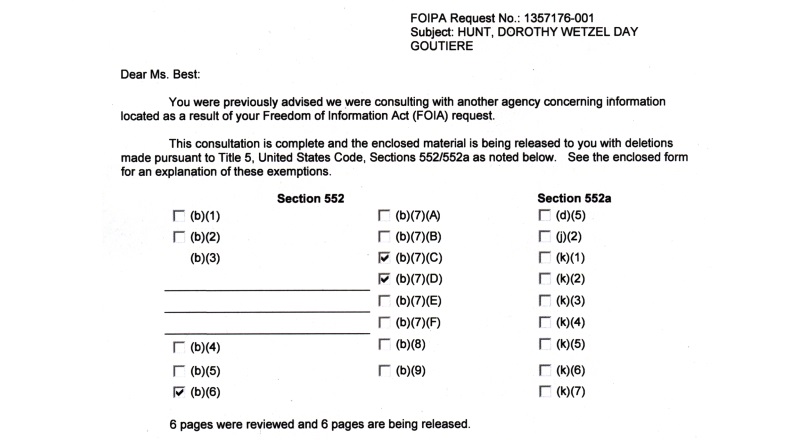

Another FOIA request for files on Dorothy Hunt was filed in August 2016. This time, the Bureau took about 14 months to respond. Despite being given less information than before (with the exception of mentioning that Dorothy Hunt was listed on the FBI’s Dead List), the Bureau was suddenly able to find six pages of documents. The Bureau did not return other known documents about Dorothy Hunt, including ones it had released separately regarding her death. Curiously, the FBI’s release letter claimed that they had previously stated that they were consulting with another agency about the FOIA request. A review of the FBI’s letters and emails shows that this assertion is false.

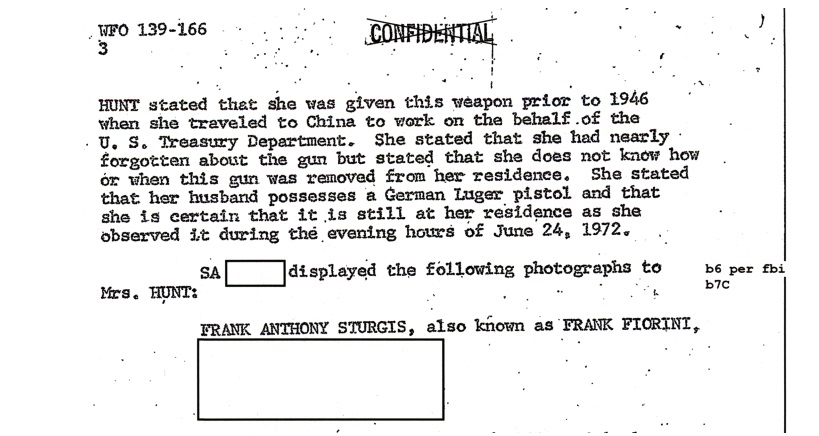

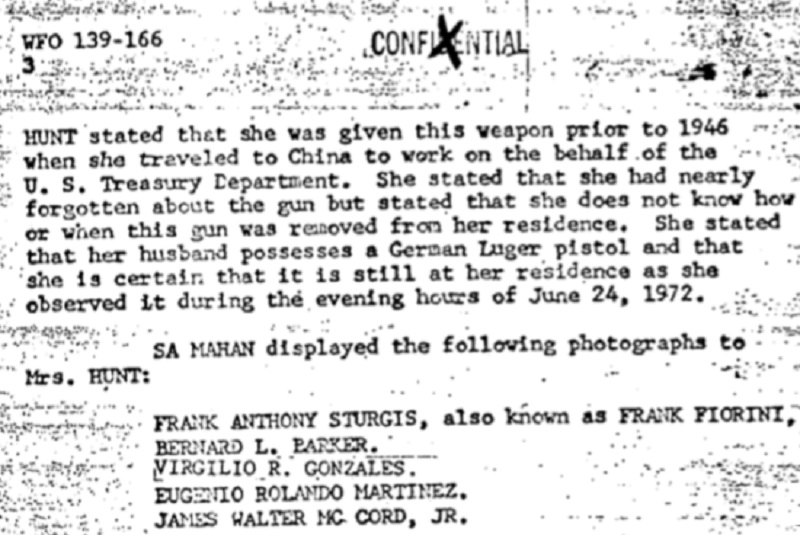

The release itself is problematic, due to some of the redactions. Arguably the most significant example is the Bureau’s redaction of a list of names of individuals who the FBI showed Dorothy Hunt pictures of, asking her to identify them. Of the five individuals, only one name is unredacted - Frank Sturgis’. The remaining names are redacted under b(6) and b(7)c - privacy exemptions.

The FBI’s redaction of these names is beyond questionable - it’s unambiguously inappropriate. An independently obtained copy of the file confirms that the remaining names were the other Watergate burglars: Bernard Barker, Virgilio Gonzales, Eugenio Martinez and James McCord. When it comes to the Watergate affair, the infamous Watergate burglars have no expectation of privacy due to the high profile nature of the crime. The Bureau’s website has their names unredacted in various Watergate files (more easily searchable copies may be found here). Not even the right to be forgotten or practical privacy can be said to apply here, as none of the Watergate burglars have been forgotten by history, the news media, or the Bureau’s own publications.

Making the matter even more egregious, one of the redacted names, Bernard Barker, belongs to a dead man. As the National Security Archive points out, “the agency generally cannot invoke the privacy exemptions to withhold information” for someone who is dead. While there are exceptions to this, they generally involved either the privacy of surviving family (both chosen and biological). As the DOJ notes, the Supreme Court has found that this only applies to protecting surviving families’ “own privacy rights against public intrusions long deemed impermissible under the common law and in our cultural traditions.” No part of common law or cultural traditions would justify the FBI redacting the identities of a deceased Watergate burglar (or the still living ones, for that matter).

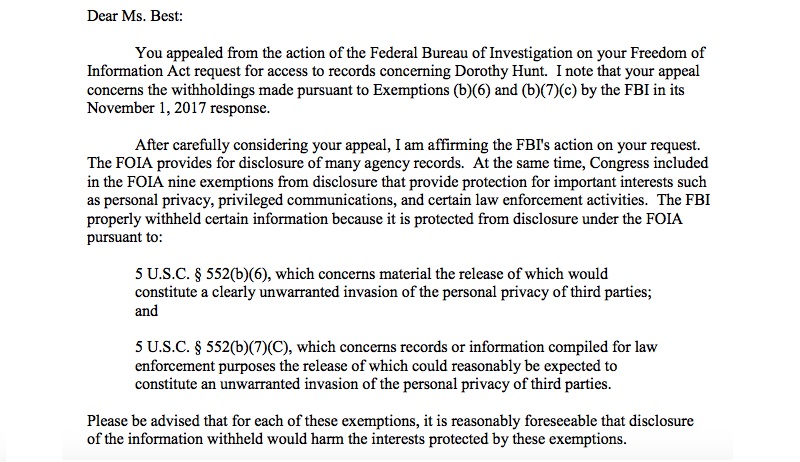

When the matter was appealed to the DOJ, noting that the FBI’s redactions included the name of a deceased Watergate burglar, the DOJ responded by upholding the Bureau’s decision, stating that “it is reasonably foreseeable that disclosure of the information withheld would harm the [privacy] interests protected by these exemptions.”

While a lawsuit might compel the FBI to unredact the names, the matter is largely moot due to the names being revealed in a separate copy of the file. The affair, however, is a stark reminder of the FBI’s and DOJ’s habit of inappropriately redacting information and refusing to correct their errors. The issue is a clear demonstration of the flaw in the FBI FOIA office’s “when in doubt, cross it out” policy of automatic redaction.

FBI's attitude towards #FOIA and excessive redactions is spelled out pretty neatly by the sign they hung in their office:

— Emma Best (ᴜ//ғᴏᴜᴏ) 🏳️🌈 (@NatSecGeek) December 7, 2017

"WHEN IN DOUBT - CROSS IT OUT" pic.twitter.com/Q8LYVrdIqs

Despite the excessive and unreasonable redactions, the file sheds light on one Watergate mystery - the contents of portions of Howard Hunt’s White House safe, portions of which were destroyed by the FBI and other segments not having been previously disclosed to the public. This aspect of the file will be explored in a future article as part of a series of forthcoming MuckRock articles examining overlooked aspects of the Watergate affair.

Read Dorothy Hunt’s file embedded below, or on the request page.