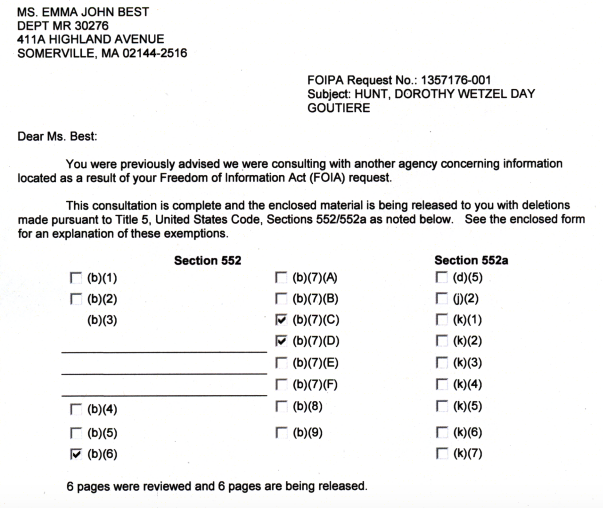

A recently released Federal Bureau of Investigation file, which the Bureau previously said they couldn’t find any record of, sheds a sliver of light on an enduring Watergate mystery: the contents of E. Howard Hunt’s White House safe, which was cracked open and its contents eventually given to the FBI after the Watergate arrests. In typical fashion for matters that touch on the Central Intelligence Agency (including anything involving Hunt), the answers offered up by the FBI file raise additional questions when they’re interrogated.

The released file is short, and consists of an FBI interview with Dorothy Hunt, the wife of Howard. Dorothy infamously died in a plane crash while transporting $10,000 in Watergate hush money five months after her interview with the FBI.

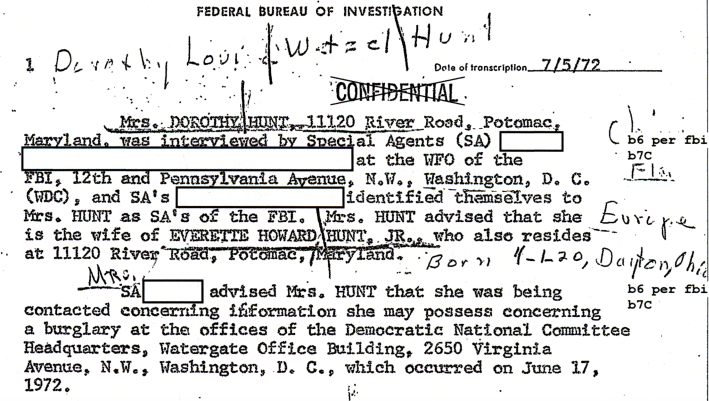

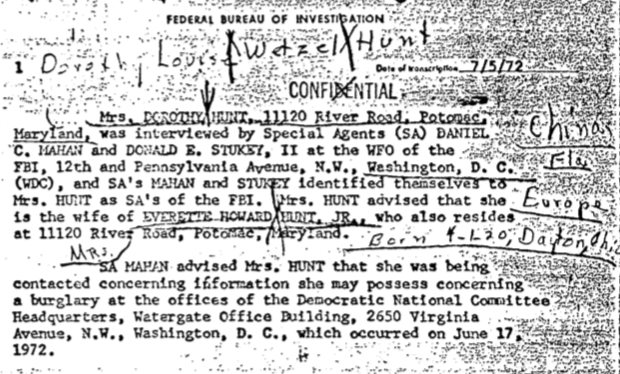

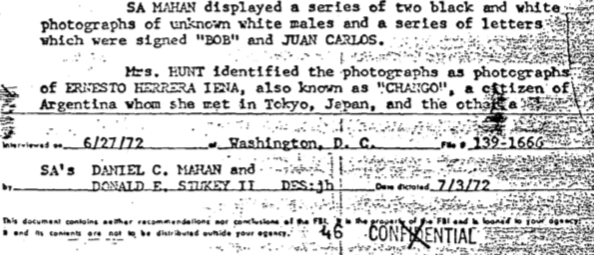

Although their names are redacted in the FBI’s latest release, another copy of the document reveals their identities: Special Agents Daniel Mahan and Donald Stukey. This comes from a copy released decades ago, and which redacts a considerable amount of information which the FBI has released to MuckRock. The names of certain individuals, including those with no expectation to privacy, is the one thing which the FBI decided didn’t qualify for a redaction before, but does now.

Dorothy began the interview by stating that she didn’t know anything about the break-in, but that she doubted Howard had been associated with any of the other burglars. The redacted file, put into context, appears to show her contradicting this statement before the FBI ended the interview.

The FBI proceeded to show Dorothy a series of photographs and letters, many of which she was promptly able to identify. Five of these photographs were of the Watergate burglars, whom she connected to her husband. Significantly, her statement of meeting one of the burglars through her husband at the 1971 Bay of Pigs reunion lends credence to later statements that this was when and where Howard Hunt reconnected with Bernard Barker in the lead-up to the Watergate affair.

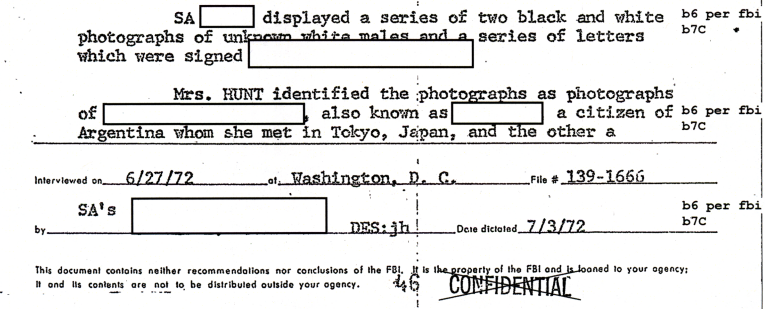

The agents proceeded to provide Dorothy with “a series of black and white photographs … and letters.” She identified the individuals who sent the letters and appeared in the photographs, though their identities are redacted in the FBI’s latest release.

The previous copy of the file reveals them to be “Bob,” Juan Carlos Quagliotti, Ernesto Herrera Iena AKA Chango.

While the prior release revealed their identities, it redacted all information about her relationship with them, citing privacy concerns and classified information.

The file the FBI released to MuckRock, however, leaves these passages almost entirely unredacted. According to Dorothy, her marriage had been strained in the late ’50s and early ’60s, with both her and her husband carrying on extramarital affairs. The letters and photographs were of and from her former lovers.

Their marital problems were reportedly bad enough that they had considered ending their marriage, but decided against it due to their children and financial issues. Dorothy told the Bureau that when they decided to try to make their marriage work, she admitted her affairs and gave the letters”, photographs and other materials she had received from these individuals. She assumed that he had destroyed them, at her request.

It’s not clear why Howard saved the letters and photographs. One of the children of the Hunts, St. John, was unable to recall hearing the names. A possible hint may be found in Inside the Company: CIA Diary, the expose (allegedly sponsored by Cuban intelligence) by former CIA employee Philip Agee. Agee’s book, which led to the passage of the Intelligence Identities Protection Act, names many names - Quagliotti’s among them.

According to Agee, Quagliotti was a Uruguayan lawyer and rancher, and a “political contact of the Montevideo station.” Possibly assigned the cryptonym AVIATOR, Agee described Quagliotti as “concerned with the decline in governmental effectiveness” and as “active in trying to persuade military leaders to intervene in political affairs.” Agee noted, however, that while the Agency had contact with Quagliotti, it did not “finance or encourage him.” Agee’s most interesting claim about Quagliotti relates to “a flurry of security moves” that he caused at the end of May, 1965.

Quagliotti was reportedly arrested for “the printing and distribution of a distorted version of an article written in 1919 by President Beltran’s father, on justification of military intervention in politics.” The matter was referred to the military courts when the original judge refused jurisdiction over the case. Contact with Quagliotti was suspended as “a wave of ill-feeling in the police” spread and resentment against the police broke out in some military circles as a result of Quagliotti’s arrest. The military court also refused to take jurisdiction “thanks to Quagliotti’s friends among the senior military officers.”

Dorothy’s affair with at least one CIA contact and agitator is especially curious given that she had, like her husband, worked for the U.S. government and that according to a book co-written by Howard, she had also acted as a source and asset for CIA. Did she eventually pass that information on to Howard? Did she provide Howard - and the Agency - information about Quagliotti when she confessed the affair, like she had previously done with information whisked from the Argentinian embassy?

Her statement to the FBI implies that the affairs continued through the “early 1960s,” which is vague enough to potentially overlap with Quagliotti’s controversy in 1965. However, their time in Montevideo ended in 1960. While it’s an easy inference that the affair ended at the time, Dorothy’s retention of the materials through the early 1960s raises the question of whether or not it ended entirely. Regardless of whether the affair resulted in information being passed on, the couple’s extramarital affairs were truly unrelated to Watergate, and all but forgotten by the FBI and Congressional investigations.

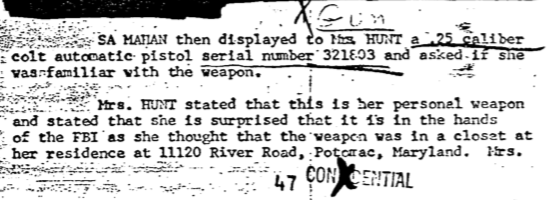

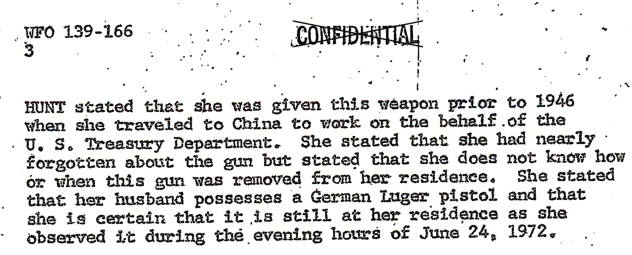

The interview does raise one other mystery - that of her revolver. The FBI presented Dorothy with an automatic Colt revolver with a pearl inlaid handle, serial number 321803. During the interview, asking if she recognized it. She told the agents that it was her “personal weapon,” and that she had thought it was in a closet at home.

She told the FBI that she had been given the pistol “prior to 1946 when she traveled to China to work on behalf of the U.S. Treasury Department.” According to her controversial son, St. John Hunt, she had told him that “she obtained her .25 cal semi automatic pistol while she was in Bern and told me she kept it within reach during these midnight trysts.” Dorothy reportedly transferred from Bern to China in 1946.

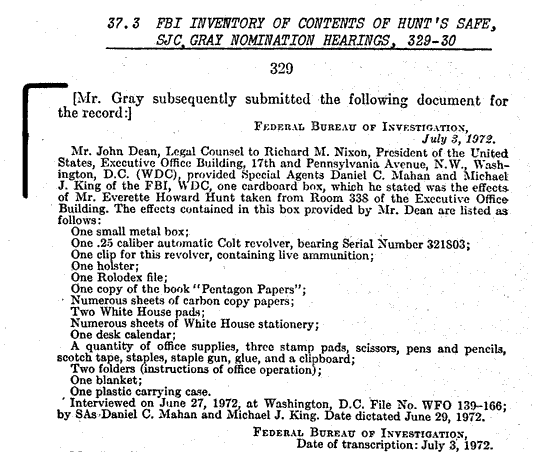

While one of St. John’s books speculated that the FBI might have secretly entered the house and retrieved the gun for some unknown purpose, records and oral histories confirm that the pistol had been retrieved from Howard Hunt’s safe in a move ordered by John Dean. The Bureau received custody of the gun the day before interviewing Dorothy. Coincidentally, one of the two agents who retrieved the boxes containing most of the materials retrieved from Hunt’s safe was one of the two agents interviewing Dorothy.

While this addresses the question of when and how the FBI gained possession of the revolver, it raises the question of how and why it came to be in Howard Hunt’s safe. This is especially curious in light of him having his own Luger, which Dorothy had reportedly seen at home three days prior to her interview with the FBI. It might have been because the gun could be connected to Dorothy’s government service, or it could have simply been a preference for that weapon over the luger. With both Dorothy and Howard deceased, and their children already stumped by the matter, this particular Watergate mystery may endure.

Read Dorothy Hunt’s file embedded below, or on the request page.

Image via Wikimedia Commons