Austin Evers is the executive director of American Oversight, an independent watchdog that uses litigation to access documents the public is rightfully entitled to under FOIA protections. After serving as senior counsel to the State Department for transparency-related matters under the Obama Administration, Evers founded American Oversight in response to the election of President Donald Trump.

Evers shared his experience in FOIA litigation and offered advice to requesters in an interview with MuckRock, lightly edited below.

How did you first get into public records litigation?

My first foray into it was as a political appointee at the State Department during the last administration, where one of my jobs was to help build, prepare for, and respond to public records publications. I didn’t actually work on the requests themselves, but if they created legal exposure or generated public comment, my job was to provide legal advice on how best to navigate those situations.

And has that always been an area of interest for you?

My background is as a civil and white-collar litigator. I’m an attorney by trade, and when I went to the State Department, it was because the department was facing an onslaught of investigations, including public records requests about Benghazi, and I worked on that and all the issues that flowed out of it.

What inspired you to found American Oversight?

I was quite troubled by the election of Donald Trump and his posture toward towards public service as a private enterprise, and I was also concerned that there didn’t seem to be any transparency watchdogs that planned to be antagonistic toward the administration. We had faced such high profile and aggressive litigation during the last administration that I wanted to model to make sure that this administration was held accountable.

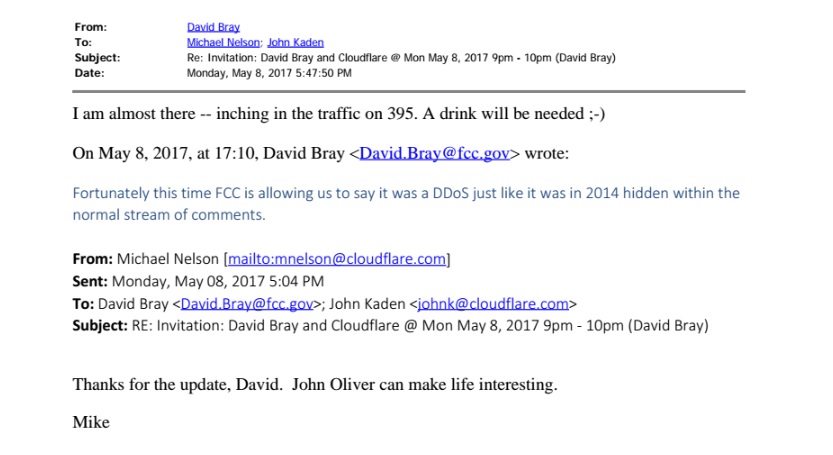

Last year, American Oversight launched an investigation into the Federal Communication Commissions’s net neutrality repeal, and last July, you sued the FCC after it didn’t respond to several FOIA requests for records related to net neutrality. Most recently, you received FCC records about its cover-up of a comment system crash. Could you please walk me through the steps you and your organization took to successfully sue the FCC and retrieve the documents you requested?

It’s a good example of what we’ve done dozens of times. We actually have over 40 pending lawsuits across the federal government.

We identified an issue that we thought was of high public interest but deserved greater public scrutiny. We exercised our rights under the law to file public records requests and then doggedly pursued them by first engaging with the agency to see if they would release documents within the right timeline, and then when they didn’t do that, we sued them. This is where we distinguish ourselves is that by litigating, we solve one of the fundamental challenges that’s at the heart of the public records system, which is that whether through a lack of resources or obstruction, it’s very difficult to get information in a timely way.

The lawsuit that we filed with the FCC was over net neutrality, and through that, we established ourselves as quite an advocate on that issue and interested in that issue. Since we’d already shown the FCC that we weren’t afraid to sue over net neutrality related documents, the FCC gave us the comment system crash records without a fight. That’s actually a really wonderful example of how our engagement in litigation identified us to the FCC as a requester who’s willing to go to court.

From the past year or so working with American Oversight, what particularly interesting or new dimensions of FOIA and transparency have you encountered?

Well, I think what’s different about American Oversight and our experience is our approach to FOIA litigation, which is where we fundamentally emphasize working within the law to ask for what we’re entitled to, and we’re sticklers for ensuring that we receive it.

I think a lot of FOIA requesters ask for things that the law doesn’t actually give them, such as classified information or privacy-protected information or internal deliberations, which are all something that agencies can lawfully withhold.We’ve had success by trying to carve those excluded categories out of our requests so that agencies can’t use those arguments against us. We’re overwhelmingly fighting with the law on our side.

The other thing I would say that has been wonderful to see is there is a voracious appetite in the media and in the public for public records. Journalists can’t pursue all the FOIA requests that they’d want to, and certainly they can’t litigate all of them, so we feel very proud that when we devote resources to fight in court for transparency, there is a ready group of journalists across the country who want to fold those into their investigative reporting to tell the American people what’s going on in their government.

What are some of the other investigations American Oversight is currently working on?

We have quite a few requests and lawsuits pending at the Environmental Protection Agency focusing on the administrator’s excessive spending and his close partnership with polluters. We even had some amazing success just by litigating to get his calendar last year, one of the most basic elements of transparency: what is your public servant doing with his time? By extracting that information, it revealed an EPA agenda that was at odds with the traditional mission of the agency.

We’ve also litigated against Housing and Urban Development to learn more about Ben Carson’s spending as well as his very cozy relationship with his family members who don’t work for the agency, and we helped expose some things that reveal nepotism.

Another interesting one that I would highlight – though it’s not a FOIA lawsuit – is we have a privilege representing the secretary of state of Maine, who was on Trump’s Voter Integrity Commission, or Voter Fraud Commission. He felt that he was being excluded from commission activities and being denied access to documents that other members were circulating and discussing.

There’s another law similar to FOIA that’s called the Federal Advisory Committees Act, and it has a transparency component and when you’re a member of a commission, you have a super-right to transparency. We litigated on behalf of the secretary of state of Maine, and we won in an amazing decision in December ordering the commission to start turning over records to our client. When the administration was faced with the prospect of transparency, they decided to shut the entire commission down, which we think spoke volumes about what the commission was doing behind closed doors, and it spoke volumes about the president’s complete lack of interest in transparency and accountability.

Previous to founding American Oversight, you worked as Senior Counsel to the Department of State on transparency-related matters. What are some of the scenarios in which the Department would seek your counsel, and how would you function in those situations?

My job was to sit at the center of investigations that were being conducted by the press, by FOIA litigators, and by Congress. For example, if a document was going to go out to Congress that was relevant to a pending FOIA case, one of my jobs was to identify that document so that everybody who was asking for that document got it at around the same time.

Meanwhile, it was also part of my job to counsel senior officials at the state department about how the law required transparency and how it was better to live with transparency and explain your conduct than to try to obstruct.

It’s a challenging issue to do work under the glare of the media or public scrutiny, but it’s something that I think is at the heart of the oath every public servant takes.

From your litigation experience, what have been the most rewarding cases you’ve worked on?

I would have to say the voter fraud case for secretary of state Matthew Dunlap was the most rewarding case I’ve done at American Oversight, and my fingers are crossed, we are not done with that litigation. A judge is still preparing to rule on whether he has a right to access the documents he was denied in the past, and I think they will tell a very important story, and this team was frankly privileged to get to know an extraordinary public servant up in Maine.

There are other cases that I think have been rewarding as well, but I’ll speak to them as a category. In cases where we find an overlapping interest with journalists or investigators in Congress, where our litigation supports the accountability work of other lovers of our democracy is fundamental to why we founded this organization, so when a reporter for The New York Times or The Washington Post or CNN is able to use our documents to get straight answers out of the administration, that’s a huge win for us, even if the documents themselves aren’t the center of the story.

What is your advice to people who want to file better public records requests?

- Know what you’re entitled to.

Unless you want to spend your life changing the law through litigation, draft your requests to ask for what you’re entitled to. Don’t spend your time and resources fighting to get access to classified information or attorney-client communications because it’s a losing battle, and it’s better to emphasize what you can get than what you can’t. And that all boils down to drafting your requests with precision and being informed of what the law is.

- Advocate for yourself.

I strongly recommend every FOIA requester be a squeaky wheel. Bureaucratic backlogs are a real thing. Resource constraints are a real thing, but nothing prioritizes a task for a public official like someone demanding their attention. Too many people send in a FOIA request and then lament that it will take five years for it to be responded to. You can change that through advocacy, even if you’re not a lawyer.

- Build a relationship with a lawyer.

It’s worth building a relationship with either an organization like mine or lawyers either within your organization, within your newsroom, or externally who are interested in pursuing litigation to back up your FOIA request. FOIA litigation is not really complicated, but it is litigation, and it requires a lawyer. It is the number one way to force transparency when an agency is trying to cut corners.

- Publish the documents that you get.

Too many people treat FOIA like an exclusive scoop and never release the documents they receive unless they can find a splashy way to publicize them. Document releases through FOIA belong to the public, and even if you don’t know how to make use of it yourself, that doesn’t mean someone else won’t.

Do you have anything else on the note of FOIA and transparency generally?

FOIA has never been more important than it is today. There’s a real interest for accountability and transparency from the public and there’s a real resistance to it on the part of our current political leadership, so I encourage everybody to join us in the fight.

Image via American Oversight