Our research shows that 173 agencies from 23 states and the federal government accounted for roughly 2.5 -billion license plate scans in 2016 and 2017. The remaining 27 agencies refused to turn over reports on how much data they collected.

The records also show that, on average, law enforcement agencies were sharing data directly with around 160 other agencies. Most agencies were also adding to a pool of data shared by hundreds of other unidentified entities.

This unprecedented scale of data collection and sharing should alarm every driver on the road. The use of ALPR has created the digital equivalent of a massive police force keeping tabs on everywhere you go, potentially capturing information such as where you worship, what doctors you visit, and where you sleep at night. It also creates an enormous potential for abuse: we have long known that law enforcement officers abuse databases for personal reasons, such as spying on former spouses. In addition, the more data is amassed, the bigger the risk if that information is breached by hackers. It’s with these concerns in mind that we embarked on this project: to help the public understand the scope of data sharing and the need for appropriate policies protecting its use and the public’s privacy.

MuckRock currently has a database of contact information for filing public records request with 12,000 government agencies throughout the country. EFF compiled a list of law enforcement agencies believed to be using Vigilant Solutions’ product, and those departments that weren’t already in MuckRock’s collection were added to the organization’s ever-growing collection of offices subject to public records laws. Then, using MuckRock’s multi-request feature, which allows us to submit the same request to multiple agencies at once, we’ve submitted requests in waves since February. To date, almost 600 requests have been filed to agencies in every state. So far, we’ve focused most of the requests in states like California (147) and Georgia (116), where Vigilant Solutions’ technology is most concentrated.

Choose a marker below to be directed to the existing request for each existing agency.

Who’s Sharing with Whom?

In its marketing materials, Vigilant Solutions tells customers, “Joining the largest law enforcement LPR sharing network is as easy as adding a friend on your favorite social media platform.” With that in mind, we asked each agency to disclose who it is sharing data with and from whom it is receiving data. This includes when agencies are sharing “hot lists” - the ALPR equivalent of a watch list. Generally, this information is included in a standard document called a “Data Sharing Report” that can be easily exported from Vigilant Solution’s LEARN software platform.

As it turns out, some agencies are friendlier than others. A majority of those we asked share their data with hundreds of agencies themselves directly or through Vigilant Solutions’ National Vehicle Location Service (NVLS), a pool of data accessed by scores of agencies, the identities of which are not readily apparent in the records. (In 2014, Vigilant Solutions claimed that sharing with NVLS made data available to 3,000 agencies and 30,000 law enforcement employees. However, that was when Vigilant Solutions provided access to NVLS free of charge, which seems to no longer be the case. Records now indicate it is still shared among hundreds of agencies. Vigilant Solutions declined to provide more information about NVLS.)

This large-scale sharing is important - and worrisome - for several reasons.

First of all, there’s the cybersecurity threat: the more widely data is shared, the more users have access to the data, therefore increasing the potential for abuse or breaches to occur without being caught. A police department in Washington, for example, has next to no ability to oversee sheriff’s deputies in Texas.

Secondly, legal requirements on the treatment of ALPR data differ state to state, and each agency crafts its own policies for controlling and overseeing that data. It’s unclear which policies and laws govern ALPR data when it crosses state boundaries. For example, a sheriff’s office in California may require officers to attach a case number to every search of ALPR data, whereas a police department in Georgia may not have any similar requirements. Meanwhile, Georgia law requires ALPR data to be destroyed after 30 months, whereas other states may allow agencies to hold onto the data indefinitely.

Of the 200 agencies we have received records from, 130 reported that they were sending data to Vigilant Solutions’s NVLS. Ten agencies were directly sharing with in excess of 800 other agencies in addition to NVLS. The following data comes from the agencies’ responses to our public records requests:

The 800 Club: Police Agencies Directly Sharing Data with More than 800 Other Agencies

| Law Enforcement Agency Name | How Many Other Agencies Does It Directly Share Data With? | Does the Agency Share with the NVLS Pool? |

| Burr Ridge Police Department, IL | 851 | Y |

| Merced Police Department, CA | 838 | Y |

| Sacramento County Sheriff's Office, CA | 838 | Y |

| Hiram Police Department, GA | 833 | Y |

| Munster Police Department, TX | 827 | Y |

| Austin Police Department, TX | 817 | Y |

| Guadalupe County Constables, TX | 816 | Y |

| Lafayette Police Department, IN | 814 | Y |

| Sacramento Police Department, CA | 809 | Y |

| Byron Police Department, GA | 804 | Y |

Only eight agencies reported that they were not sharing any of the data they collected with other agencies: Beverly Hills Police Department, El Dorado County Sheriff’s Office, Manhattan Beach Police Department, Oxnard Police Department, Pomona Police Department, and Redlands Police Department in California, Bristol Township Police Department in Pennsylvania, and Mounds View Police Department in Minnesota. However, most of these agencies were given access to data from scores of other agencies.

It’s important to note that 15 agencies provided no information or incomplete information about data sharing, despite our explicit request. The U.S. Forest Service, for example, redacted nearly the entire Data Sharing Report, although we were able to extrapolate from the size of the redaction that it was sharing data with at least 390 entities.

One of the main reasons for requesting this data, beyond simply informing the public, is to force agencies to confront the sheer amount of sharing going on and, hopefully, exert some quality control.

One good example of this is the Hawthorne Police Department in California. In May 2017, long-time EFF friend Mike Katz-Lacabe of the Center for Human Rights and Privacy received records from Hawthorne showing the agency was directly sharing data with 132 agencies and 462 agencies through NVLS. Records we received in October 2018 shows Hawthorne is now only sharing with six local agencies and is no longer sharing data with NVLS. We don’t know for certain that it was public scrutiny that lead Hawthorne to curtail its rampant sharing, but we have a pretty good guess.

Lack of Awareness

One surprising discovery was that sometimes agencies seemed unaware that their staff accessed ALPR data.

The Tarrant County District Attorney’s Office, for example, originally claimed they had no information responsive to our requests, because neither it nor the Tarrant County Sheriff used ALPR technology or software. We responded with evidence from the Tarrant County Board of Commissioners and the Tarrant County Auditor’s Office that the agency had spent nearly $5,000 on Vigilant Solutions software in 2017. The District Attorney then provided records showing that its employees were able to access ALPR data from 522 agencies through NVLS.

The Ontario Police Department in California made similar claims initially, also later proven false. “We do not currently have a relationship with Vigilant Systems,” the Ontario Police Chief’s representative wrote via email. “We neither input or share information with other agencies nor do we have access to their system(s).” A month and a half later, the representative emailed again, saying: “Apparently the information I was given had not been updated when I inquired. We do currently have a relationship with Vigilant Solutions.” A record was provided showing the agency was receiving records directly from hundreds of agencies.

The Data Sharing Reports generated by Vigilant Solutions’ system names the agencies involved in data sharing, but the reports do not always name the state where the agency is located. Since many cities and counties share the same names, many agencies may not even themselves be clear who they are sharing data with.

For example, at least 18 agencies we surveyed reported they were sharing data with the Midlothian Police Department. However, Midlothian is the name of a village in Illinois with a population of approximately 15,000 and the name of a city in Texas with a population of approximately 25,000. So which one is it? We filed public records request with both municipalities and discovered that it was, in fact, the Midlothian in Texas.

However, many agencies might think they are sharing with Midlothian in Illinois, because that agency too used to be a Vigilant Solutions customer. As an agency representative told us in response to our public records request: “We have confirmed with our Police Department and they have advised that Midlothian had an account to [NVLS] in 2013-2014 when the system was free. They began charging extensive fees in 2014 and we no longer have an active account.”

This information may go a long way to explaining why so many agencies have had access to ALPR data: Vigilant Solutions was giving it out for free.

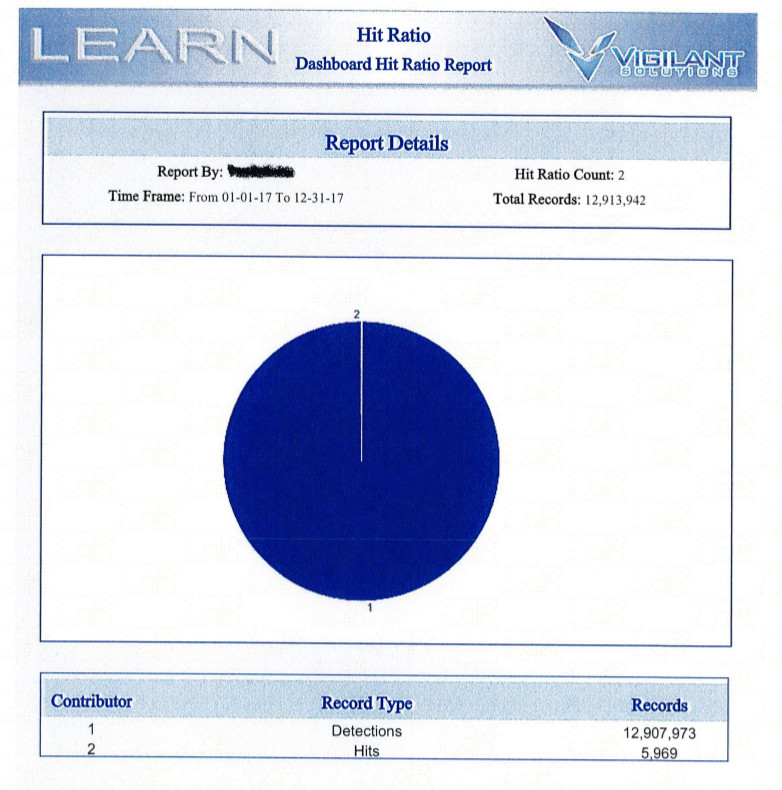

Understanding the “Hit Ratio”

In addition to asking each agency how much data they collected in 2016 and 2017, we asked agencies to disclose the number of “hits” they recorded for each year.

Many agencies that use Vigilant Solutions also use a function called “hot lists.” Each hot list is a list of license plates for which agencies are actively looking, usually because the cars have been reported stolen or are believed to be involved in a crime. For example, for the purposes of an AMBER Alert, an agency may add the suspected kidnapper’s license plate to the system in order to get alerts whenever the vehicle is seen by ALPR. However, the lists might also include people on probation or parole or who have outstanding court fees or expired insurance.

To determine the hit ratio, you take the number of “hits” and divide it by the number of “detections.” You may then multiply the number by 100 to get a percentage.

On average, only .5% - that is, one half of one percent - of license plate scans were attached to a hotlist. This means that 99.5% of the license plates captured by ALPR are actually not connected to a public safety interest at the time they are captured.

To put it another way, the overwhelming majority of the data is not relevant to crime. For example, the Galveston Auto Theft Task Force in Texas recorded the largest number of plate scans of the agencies we surveyed—765,277,845 plate scans in 2016-2017. Only .1% - one in 1,000 scans - were on the Task Force’s hot lists.

It is important to note that agencies often do not have clear policies for how a license plate is added to a hot list or any established thresholds that must be met before a person can be tracked in near real-time by ALPR. As a result, certain agencies that had an extremely high hit ratio warrant further investigation. For example, the Kansas City Police Department in Missouri reported that almost 7.6% of the 37 million license plates it scanned in 2017 triggered a hit—indicating that an unusually large number of vehicles in the region have been added to a hot list. We’re not sure what could explain this hit rate, and it’s worth further exploration by the local press.

Approximately 35 entities did not provide records related to detections and hits.

Who Was Super Secretive?

Fortunately, only 24 of the 582 requests filed as of today have been outright rejected. While a majority of these occurred in states where records requests are restricted to residents—including Tennessee, Virginia, and Alabama—many of the others contradicted other agencies within their states with unique ways of rejecting our requests.

In Georgia, for example, 27 police departments easily fulfilled our requests, while five found arguably inappropriate ways to deny us. The Fitzgerald Police Department in Georgia simply sent back a copy of our request with the words, “Under Title 35 these records are not subject to open records.” Aragon Police Department improperly applied a new law written to protect the data itself in order to deny the request for information about the departments with whom it is sharing that information. Moultrie Police Department provided multiple reasons the records might be denied, including the department’s policy of not mailing, emailing, or faxing records. Calhoun County suffered a server failure that allegedly wiped all of its data.

By and large, most agencies provided us the information we sought at zero cost. However, a select few opted to levy charges for what should have been a simple request. For example, Maple Grove Police Department in Minnesota is asking for $47, the St. Louis County Police Department in Missouri is currently asking for $43.50 and the Conyers Police Department in Georgia is asking for $36.15 before any of them will release the records.

Click below to explore EFF and MuckRock’s dataset and learn how much data these agencies are collecting and how they are sharing it.

Introduction

Explore the data

Download the dataset

Understanding the source documents

Help us file more requests

A caveat on the data

Header image via the EFF and is licensed under CC-BY 4.0