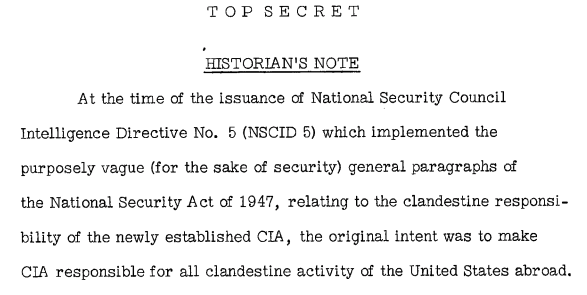

As part of MuckRock’s ongoing project to declassify and collect internal Central Intelligence Agency histories, the Agency recently released a copy of the history on the Foreign Intelligence Staff’s coordination under National Security Council Intelligence Directive No. 5, from 1951 - 1967. The history outlines various “turf wars,” some which predate the Agency itself, which were the result of disagreements about what the law said and who had what responsibilities. According to the history, many of these disagreements and differing interpretations stemmed directly or indirectly from the language of the National Security Act of 1947, which both established and empowered the CIA, being “purposefully vague.”

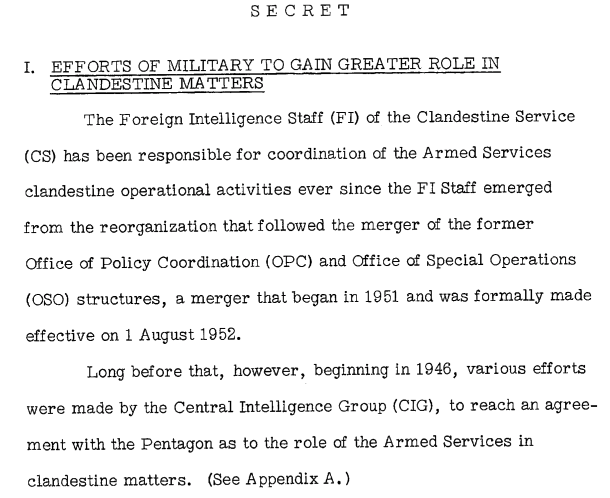

The history was written by Lloyd George, one of the people responsible for the various revisions to NSCID No. 5 along with supervising resulting coordination. While it begins in 1951 when the Foreign Intelligence Staff began to emerge as a result of the reorganization surrounding the merger of the Offices of Policy Coordination and of Special Operations, the history includes events from before either the FI Staff or the CIA were created.

In its earliest days, the FI Staff was responsible for planning, operations, Communications Intelligence, also referred to as “special intelligence” in the history. According to the history, “for a year or two, the FI Staff also handled counterespionage and counterintelligence staff functions.”

The Agency’s problems with in coordinating with the Armed Services dated back to 1946, before the National Security Act of 1947 effectively transformed the Central Intelligence Group into CIA. According to the history, this was the result of “the conflicts of personalities and concepts that marked the year and a half of struggle” to establish CIA, which resulted in “attitudes of distrust on both sides.” These issues intensified during the Congressional hearings to pass the National Security Act of 1947, in which the creation of CIA was opposed mainly by spokespeople for the Pentagon “who sought to restrict CIA operations.”

The resulting conflict became a source of increasing trouble for the Agency’s Clandestine Service “because, for half a decade, it was not entirely clear” what the Armed Services were permitted to do “under certain unexplained circumstances” that were vaguely described by the original NSCID No. 5. This resulted in “many petty but extremely bothersome conflicts in many parts of the world between local US military and CIA operators” who were separately working on clandestine intelligence gathering.

Referring to the relatively “cowboy”-ish ways of the Office of Strategic Services, the paper reported that the Agency’s methods tended to be “more careful and perhaps more consuming of time and manpower.” In comparison, the late ‘40s and early ‘50s were characterized by the Armed Services’ “frequent failure” to be “careful and detailed” in their approach to clandestine activities. This resulted in “frequent complaints” from the officers CIA’s Clandestine Services officers and their counterparts in the Armed Services.

The Agency’s description of the conflict’s equivalent in Washington D.C. is surprisingly poetic.

Things began to change in 1955, when CIA Director Allen Dulles grew tired of Congress’ reports to him on military requests that the Armed Services reported went unfulfilled because they weren’t permitted to conduct the necessary clandestine operations. To end the problem, Dulles directed that the Armed Services be able “to engage in certain operations with the proviso that they coordinate with him in advance.”

The Armed Services still rankled at the restrictions placed upon them. While DCID No. 5/1 was being crafted, the Armed Forces’ representatives worked to make it more agreeable to them. While the Agency spent 1955 and 1956 focused on getting the revised directive to the field and ensuring it was interpreted “the way that CIA intended,” the Army’s interpretation differed greatly from the CIA Director’s. Simultaneously, the Armed Services worked to seize an opportunity amid efforts to overhaul all of the NSCIDs.

The years 1960 through 1965 were a period of relative calm. While coordination issues persisted, they were rarely referred to Washington and virtually none of them had to involve the CIA Director. This period of calm was enhanced by the creation of the Defense Intelligence Agency which expanded the number of contacts with their military counterparts while increasing the complexity of those relationships.

The responsibilities of the branch of the FI Staff’ responsible for planning coordination also increased greatly in that period, particularly due to an early decision by President John F. Kennedy. In May of 1961, Kennedy sent a letter to American Ambassadors, giving them “broad powers over the activities” of US agencies working in their jurisdiction. While President Dwight Eisenhower had sent a similar letter years earlier, it exempted CIA while Kennedy’s letter didn’t. This resulted in increasingly close relations and coordination with the State Department’s office of the Director of Intelligence and Research. Kennedy’s letter also required the FI Staff to keep Ambassadors apprised of the Army’s clandestine operations, further increasing both the amount and depth of the Agency’s coordination with other parts of the government.

This letter appears to have helped put an end to some of the friction between the Agency and the Armed Services. At least some of which seems to have arisen over a matter of syntax, and whether they were to coordinate with the CIA or have their activities coordinated by the CIA.

Further disagreements arose of precisely what information the military was required to provide to the Agency in advance, and what restrictions these policies created for ordinary communications with foreign militaries.

While these negotiations were primarily handled by the FI Staff, the details were closely coordinated with and controlled by representatives of the Counterintelligence Staff and James Jesus Angleton.

On May 14th of 1957, interagency coordination reached a new level of depth with the creation of an Interagency Source Register. Agencies were required to use the Register to document foreign intelligence sources and agents, including the date and place of their birth. The ISR evolved over the next several years, culminating with a new charter in 1964.

The ISR was envisioned as a relatively all-inclusive listing that would be comprised of all foreign agents and sources of human intelligence. However, “one-time, casual and potential human sources of foreign intelligence” were eligible for the ISR only if there was an intention to recruit them as agents or sources “on a regular and continuing basis.” Foreign officials such as diplomats, military, security and police officials would be included if there was a “clandestine relationship” or the intention to develop one.

Similarly, employees of the US government would be registered in the ISR if there was or would be an approved, clandestine relationship.

The ISR was used for interagency coordination on sources, but as a source of interagency warnings in the form of burn notices which denounced the source.

Forty-eight years later, the Agency still claimed that revealing any portion of the procedures governing the ISR would compromise sources and methods. A new FOIA request has been filed to learn more about the ISR. In the meantime, you can read about it and interagency conflicts and coordination under NSCID No. 5 below or on the request page.