An improved public records law was passed on Beacon Hill two years ago, but just five miles away, the Medford Police Department continues to neglect its legal obligations to records requesters and the public.

The revised public records law went into effect last year in Massachusetts. It set deadlines for the production of records, restricted fees agencies could charge for providing documents, and most notably, permitted courts to award attorneys’ fees for successful public records lawsuits (though it didn’t make the provision mandatory, as is the case in some states).

By law, agencies and municipalities must provide a response to a records request within 10 business days. This response may be the responsive records themselves or an explanation of why documents won’t be provided within the allotted time frame - and in some situations, at all. Despite the renewed emphasis on agency obligations, some Massachusetts agencies continue to fail their citizens.

By law, agencies and municipalities must provide a response to a records request within 10 business days. This response may be the responsive records themselves or an explanation of why documents won’t be provided within the allotted time frame - and in some situations, at all. Despite the renewed emphasis on agency obligations, some Massachusetts agencies continue to fail their citizens.

The Medford Police Department is a prime example. MuckRock records show that the agency consistently fails to acknowledge and fulfill requests, sometimes for years and despite appeals to the Massachusetts Supervisor of Public Records. Its failure to comply with even the updated legislation highlights the shortcomings that remain in enforcement mechanisms for citizens entitled to government information.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, which led lobbying efforts that culminated in the recent state public records law, the revision - the first since 2013 - finally gave teeth to one of the worst records laws in the country.

Kade Crockford, the director of the Technology for Liberty program at the ACLU of Massachusetts, said she saw overnight improvements in response times to public records requests - at least to those filed by the ACLU. But the experience of the ACLU, one of the leading civil rights organizations in the country, is not representative of all those entitled to public government records.

“The ACLU is not like everyone else,” Crockford said. “When government agencies get a letter from us, they may be a lot more likely to take it seriously than they would be if they got it from a reporter affiliated with an independent news outlet or just an independent resident who is not connected to an institution with the kind of power that the ACLU or the Boston Globe has.”

MuckRock, which has been submitting requests to the Medford Police Department for over five years, has largely received no responses from the agency since 2013, even after legislative improvements.

And why?

Crockford said she assumes it’s because the MPD doesn’t think we’ll sue, a reason that emphasizes the leniency allowed by the absence of mandatory attorneys’ fees if an individual does sue over a request. In other words, agencies can bet that requesters won’t be willing to risk thousands of dollars in litigation fees that aren’t guaranteed to be reimbursed if they’re found in the right.

“If I were you,” Crockford said. “I’d prove them wrong.”

Problems of community trust are plaguing law enforcement agencies across the country, and citizens are using transparency to challenge them.

The Citizens Police Data Project, for example, revealed, through a series of public records requests, that officers at the Chicago Police Department have repeatedly and violently targeted people of color, without repercussion. The New York Police Department recently expanded its gang member database in a move that primarily targeted young black and brown people, according to public records received by a CUNY School of Law professor.

Deeply rooted corruption in police departments continues to come to light thanks to the efforts of journalists and researchers who insist on compliance with disclosure laws. Though there is little indication of immediate wrongdoing by the MPD other than its disregard for the public records law, its poor responsiveness raises questions about the way the department handles its priorities.

Other actions by the MPD also suggest questionable department discretion — perhaps at the expense of transparency and accountability. The Boston Globe reported in 2011 that MPD officers were among the highest earning city workers. The MPD department headquarters is currently slated to be rebuilt by 2020, a response to employee complaints about the conditions of the police station. The records division, however, has no clearly allocated funds in the 2019 fiscal budget, and representatives of the MPD were unable to confirm how much is allocated to the operation of the records department.

As of June 2018, MuckRock had 10 pending requests with the Medford Police Department, and though a MuckRock staff member had been calling about them every few months until that point, we began to follow up on them in earnest at the beginning of the summer.

MuckRock repeatedly called the MPD for a status update on the pending requests, and each time, a representative assured us they were being worked on. Given that some requests had been pending for years and the MPD had sent no written communications confirming its assurances, those claims were unsubstantiated.

Internal MuckRock data logging the records requests and follow-up communications sent by MuckRock support the suspicion that the MPD has ignored hundreds of emails and faxes.

Even staff turnover couldn’t fully account for the absence of a response from the MPD. The oldest pending request, dating back to April 2013, had 112 email follow-ups that were sent to an officer who, at some point since initial submission, had left the department; these were followed by 14 fax follow-up messages to a currently valid office fax number.

MuckRock provided its log of communications to the city on July 12th. Kimberly Scanlon, the records access officer for the City of Medford, forwarded this log to Elanor Whalen, the records access officer for the MPD, in an email that was also disregarded.

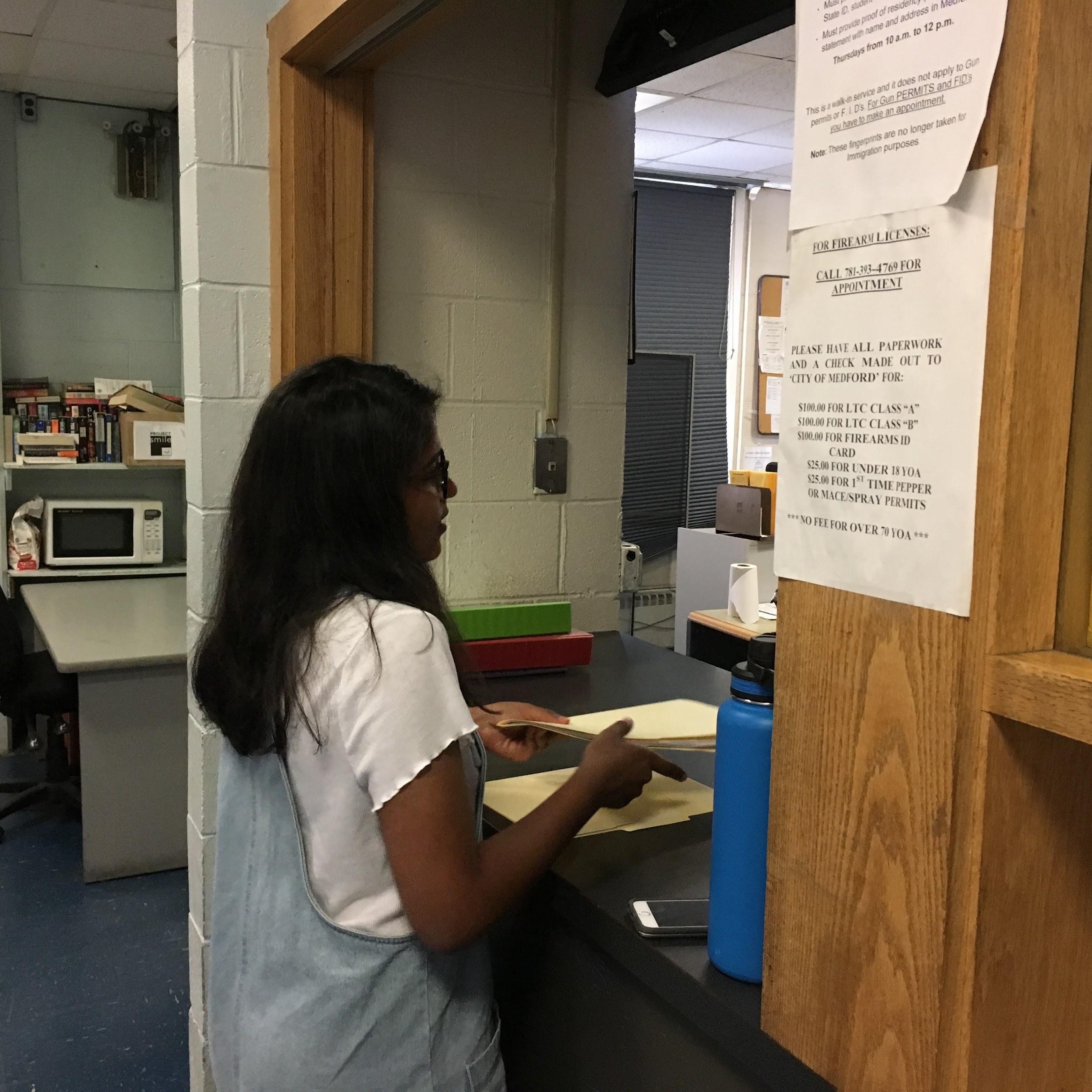

In a final attempt to receive an acknowledgement of pending requests, on July 19th, MuckRock physically brought into the station all pending requests, which Officer Thomas Maloney confirmed would be delivered to the records department.

Even that process wasn’t as straightforward for citizens as one would hope.

When first asked the officer’s name for follow-up purposes, he paused before reluctantly responding, “Maloney.” MuckRock subsequently requested his first name, which he matter-of-factly said was “Officer.” When pressed further, he finally added, “Thomas.”

Requests submitted in person - similar to those submitted via email, fax, and regular mail - must be acknowledged within 10 business days. However, the MPD also did not formally acknowledge the requests submitted in person.

At that point, it became obvious that, despite our attempts to be considerate of MPD’s other duties, further action would be needed.

Having exhausted all communication methods, MuckRock sought external intervention. In Massachusetts, the Supervisor of Public Records, located within the Office of the Secretary of State, reviews appeals and makes determinations on agency records access decisions. The SPR must provide a response to the requestor and inform the public agency in question about the appeal within 10 business days.

Fortunately, this part of the process still has some effect.

Just two days after the SPR emailed the MPD about the submitted appeals, MuckRock received responses to five requests. Most responses stated that responsive records were not available. One request turned up responsive records to a month-old request seeking a 911 call detail record, which police departments are mandated to keep.

The SPR later issued a determination ordering the MPD to provide responses to the remaining appealed requests within 10 business days.

Over one month after that SPR determination, there are still five appealed requests the MPD has not acknowledged. The SPR informed MuckRock that the office would follow up with the MPD, but, ultimately, there are limits to its enforcement of the public records law.

The SPR lacks the legal authority to enforce his own orders, which can act as an obstacle to ensuring agencies obey directives, wrote Debra O’Malley, the spokesperson for the Office of the Secretary of the Commonwealth, in an email to MuckRock. The SPR, however, can refer matters to the Attorney General’s office, which can then file an action to compel compliance in court or otherwise enforce compliance with the records law.

In all of 2017, the SPR referred eight cases to the Attorney General’s office. This year, there have been two such cases.

Since the records law has gone into effect, O’Malley reports, the number of appeals submitted annually has steadily increased, most likely because it is now easier for citizens to file public records requests.

However, the increasing number of appeals - though also indicative of an increase of requests submitted overall - suggests that agencies and municipalities are continuing to ignore requests, deny access to certain records, and overcharge for access to documents. Perhaps, the Massachusetts public records law hasn’t gone far enough.

The MPD and other municipalities aren’t obligated to report their delayed response times to the SPR, which limits its incentive to provide timely responses. Only state agencies are mandated to keep and submit public records requests logs to the SPR. State agencies and municipalities are distinguished by scope of jurisdiction.

Additionally, records requests in the state don’t require a tracking number, which can make it difficult for requesters to follow up on requests and easier for records custodians to vaguely or dishonestly confirm requests are being processed and even deny receipt of requests.

In most calls MuckRock had with the MPD, we were assured our requests were being worked on or asked to directly reach out to other officers, such as Captain Barry Clemente and Chief Leo Sacco, who were difficult to reach. The state public records law recently attempted to address requestor runaround by mandating that all agencies have a designated records access officer, but that designation has proven ineffective in this case, as responses continue to be insufficient and untimely.

In the SPR database of settled appeals, it was revealed that the the Boston Globe similarly experienced runaround from the MPD. A request for criminal complaints and incident reports was met with the suggestion to “try at reach out to the Suffolk Superior Court” without citing any exemptions or denying it had access to responsive records. The Globe appealed this response.

However, the appeal was later withdrawn once the agency finally provided the records.

This is where the experiences of the Boston Globe and MuckRock diverge. The MPD seemed quick to attend to the dissatisfaction of a major organization like the Globe, which has the resources to sue, meanwhile relegating independent journalists and nonprofits to mere noise.

Officer Eleanor Whalen said neither she nor any other member of the records department, would be willing to offer comment on these and MuckRock’s other concerns.

After five years of follow-up emails, calls, faxes, an in-person visit, and appeals to the SPR, MuckRock is essentially left how it started: with nothing. The MPD has only responded to half of the pending, appealed requests, and most responses state no responsive records exist. These responses, and lack thereof, beg the question: why didn’t the MPD just deny access to these records months, or, in some cases, years ago? And is the MPD telling us the truth when it says responsive records don’t exist?

The best way to find out is to sue. But litigating eats resources requesters typically don’t have, which is perhaps the most unfortunate implication of this saga with the MPD. Agencies that illegally ignore records requests face minimal, if any, consequences - and there’s not much most requesters can do about it.

Have your own Massachusetts records story? Let us know via the form below.

Image via Medford Police