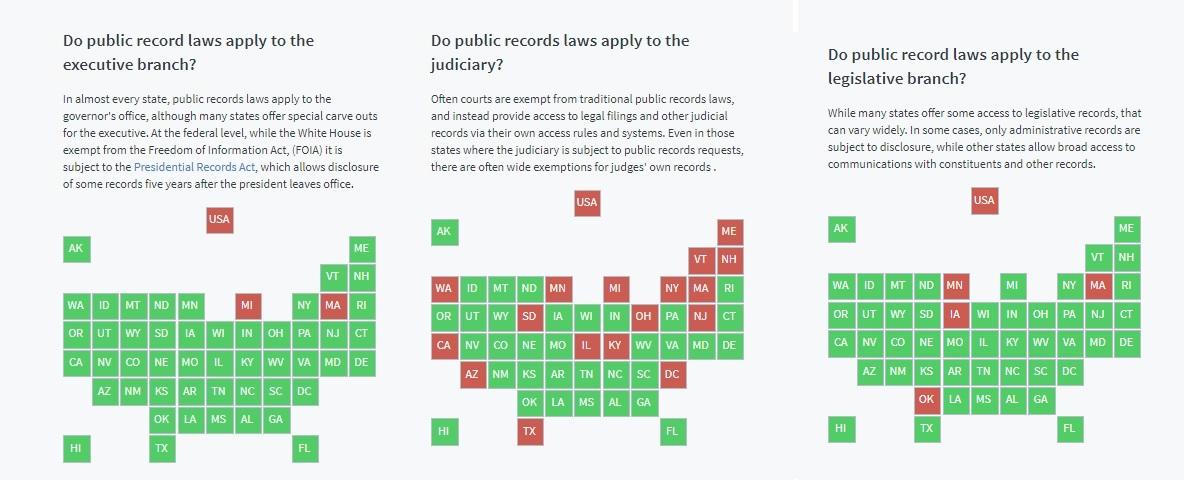

Most requesters that file in Massachusetts have noted difficulty in obtaining records from the state. The Bay State has often been ranked as one of the worst in terms public access to information, and that’s in no small part owing to the fact that three branches of government - the judiciary, the legislature, and the office of the governor - are exempt from the public records law.

Most requesters that file in Massachusetts have noted difficulty in obtaining records from the state. Massachusetts has been ranked as one of the worst in public access to information and it might be because three branches of government are exempt from the public records law.

Documents that could be public in other states, like legislative agendas or the governor’s communications, are exempt in Massachusetts. Written as law is the indefinite exemption to the public records law for the judiciary, legislature, and [the office of the governor,](despite the fact that no other state in the nation holds exemptions to these three areas (Michigan is the closest, however while an individual legislator’s records are exempt, broader legislative records are not).

“All that information is a public record and should be made public. It shouldn’t be something you go through hoops for,” said the Director of Government Transparency at the Pioneer Institute, Mary Connaughton.

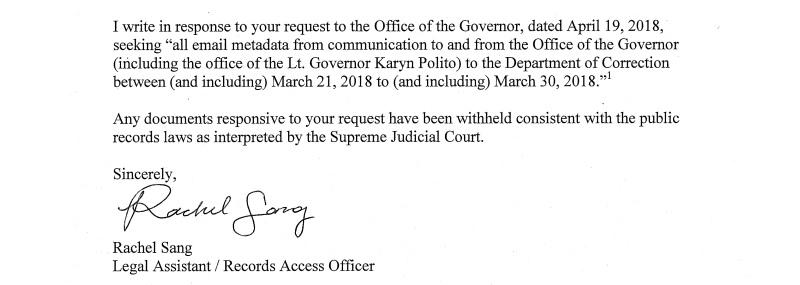

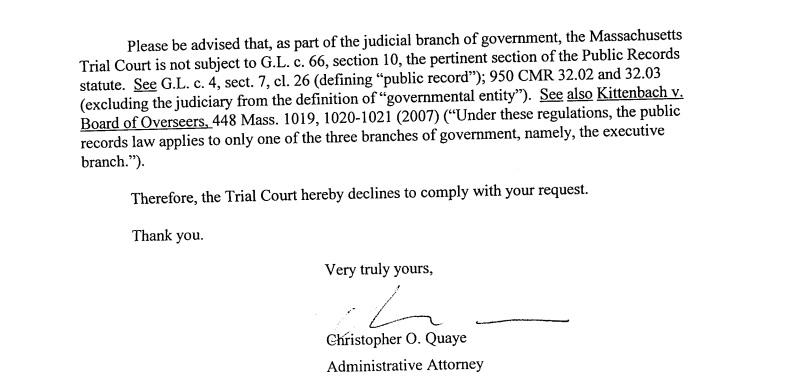

There are different legal histories behind each of the state’s exemptions. Some involve constitutional matters, and others are due to interpretation of state law by the courts. In 1997 Lambert vs Judicial Nominating Committee paved the way to uphold exemptions for all three branches of government in the state. Lambert was looking for information from the committee, but the committee fell under the governor’s office. The Superior Court in Massachusetts ruled in favor of the committee and supported their ruling by citing the law’s exemption to the governor.

“We need more transparency. Massachusetts is low on the list nationwide,” added Connaughton. “We’ve made some improvements over the years, but we need more work to make citizens more involved.”

The state’s public records law was enacted in 1973, long before the everyday reality of the internet. As technology rapidly progressed, the public records law stayed the same, until 2016. The 2016 public records reform changed key pieces in the law including the timeframe in which agencies need to respond, caps on copying fees, and the option for judgest to reward attorney fees in public records lawsuits. However, the reform left the state’s highest branches of government untouched. Instead of including these areas in the reform, lawmakers decided to create the Special Legislative Committee on Public Records to look into the feasibility of lifting those exemptions.

Representative Jennifer Benson (D-Lunenberg), co-chairs the 14-member commission and says they are still evaluating the issue of access to legislative records and the possibility of applying the public records law to other parts of state government.

“We have held five public meetings where we have collected testimony from several organizations with an interest in public records reform,” said Benson. “The 2016 Act that created the Commission gave it numerous charges, and we are working to produce a report that addresses them.”

Benson adds that the Legislature’s website was recently redesigned to be more accessible and intuitive. She notes that the site hosts thousands of documents, including every bill, amendment, budget, and committee hearing agenda. In 2016, the Office of the Comptroller launched the Commonwealth’s Financial Records Transparency Platform (CTHRU), which gives the public a comprehensive look at state spending.

But as the commission meetings progress, members have shared some of their concerns in opening up records from all three branches of government. Some are concerned about sensitive constituent information remaining private and the cost and feasibility of requiring legislative committees to post all collected testimony online. This is an issue for the commission as many committees have only two or three staffers assigned to them.

The Public Records Commission is set to report its findings in December of this year and make recommendations by then. Despite these improvements since the 2016 reform, open record advocates still feel that Massachusetts falls short on open government.

“A healthy democracy is critical and relies on citizenship engagement,” added Connaughton. “It should not be based upon the discretion of individual legislators, it should be a blanket policy that all documents are made available.”

Have your own Massachusetts records story? Let us know via the form below.

Image by Upstateherd via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0