In the midst of the Cold War, the Central Intelligence Agency routinely collected information about the methods of control employed by the Soviet Union to capture, incarcerate, and punish those opposed to the state. While the CIA used this information to denounce the USSR in reports such as this one available in the CREST archives, a modern reader will note how several of the criticized policies resemble those of the criminal justice system in modern day America.

Here are five such parallels.

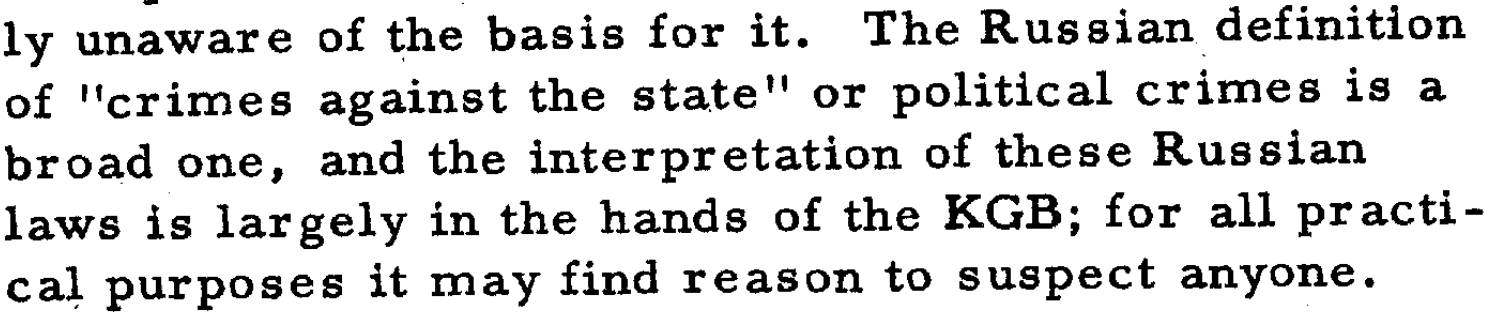

1. Broad police discretion

The Soviet Union’s infamous secret police, the Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnost, better known as the KGB, explicitly worked to detain enemies of the state. The broad nature of this mission, the report notes, allowed the KGB to exercise discretion and target groups that would “likely” have anti-Communist sentiment, such as members of the aristocratic class and people who had a history of interacting with foreigners.

Criminal justice advocates across the US today similarly criticize police departments for targeting people viewed as “high risk,” mostly in low-income communities of color, in the name of public safety. In Boston, for example, a recent MassINC report mapped the rates of incarceration and revealed that people in primarily black and brown neighborhoods were disproportionately incarcerated.

Courtesy of MassINC

2. Incentives for arrests

KGB officers and district departments were evaluated based on the number of people they arrested, which incentivized them to seek out suspects who fit the profile of potential enemies of the state, even if there wasn’t enough incriminating evidence against those suspects.

This practice can be viewed as the equivalent to the modern day use of racial profiling by police departments, in the context of the War on Drugs in particular, to receive federal subsidies for successful drug policing and seize assets from victims of (oftentimes uncalled for) drug raids. Similarly, the recent rise of algorithmic or “predictive” policing has been criticized for explicitly encouraging police to seek out crimes before they’ve actually happened.

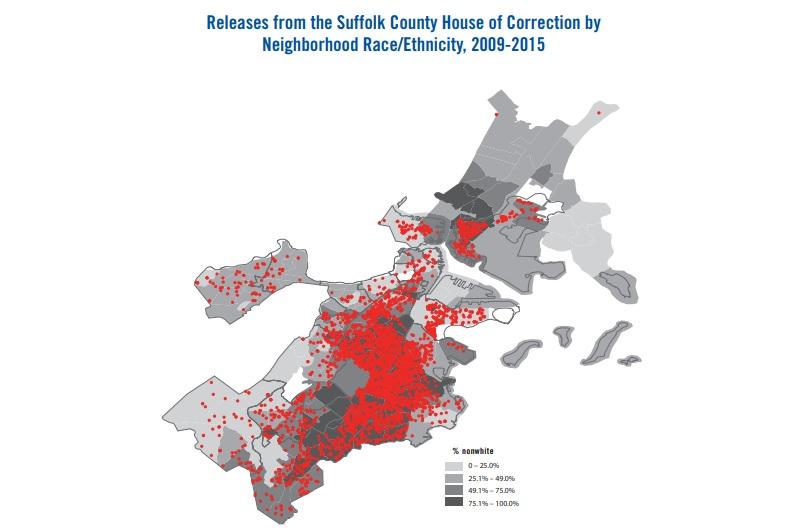

3. Guilty before proven innocent

When the KGB arrested its suspects, they were immediately labelled as criminals. KGB officers usually used harsh interrogation techniques, coercing the suspect to admit to a “crime” they may or may not have committed. These techniques proved to be successful, as approximately 85 percent of detained people under the Soviet regime were ultimately convicted.

The US today has similar success in forcing people to plead guilty even if they’re innocent, according to an argument laid out by Jed Rakoff, a senior district judge, in his paper “Why Innocent People Plead Guilty.”

Over 90 percent of criminal defendants at both the state and federal levels choose to enter a plea bargain. In these agreements, the defendant is incentivized to plead guilty and negotiate a more lenient sentence rather than risk facing a harsh mandatory minimum sentence after a long trial.

Another manifestation of the Soviet Union’s “guilty before proven innocent” approach was in its practice of holding suspects in detention prisons who hadn’t yet been convicted.

In the US, the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution states people can only be deemed guilty after due process, and Miranda v. Arizona protects detained people from self-incrimination. However, criticisms of the bail system suggest people are preemptively punished.

When a person doesn’t have the funds to put up bail or is deemed potentially dangerous, they are oftentimes forced to stay in a county jail for an indefinite amount of time before their case is reviewed.

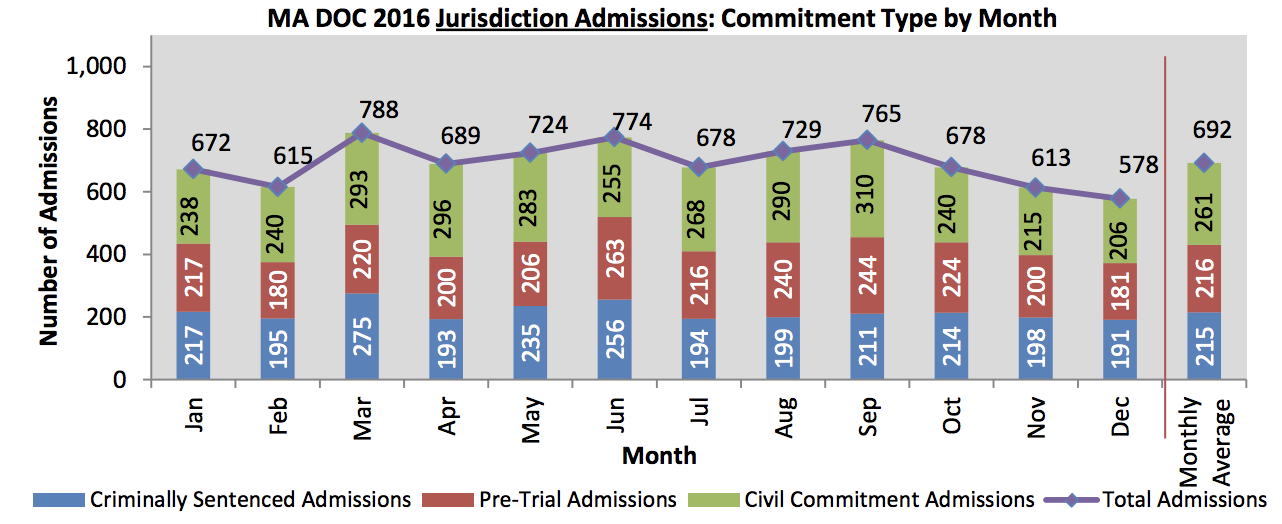

A significant portion of the incarcerated population is held without bail. In Massachusetts, for example, there were, on average in 2016, slightly more people committed to correctional facilities on pre-trial admissions than criminally-sentenced admissions every month.

Courtesy of Mass.gov

4. Prison conditions

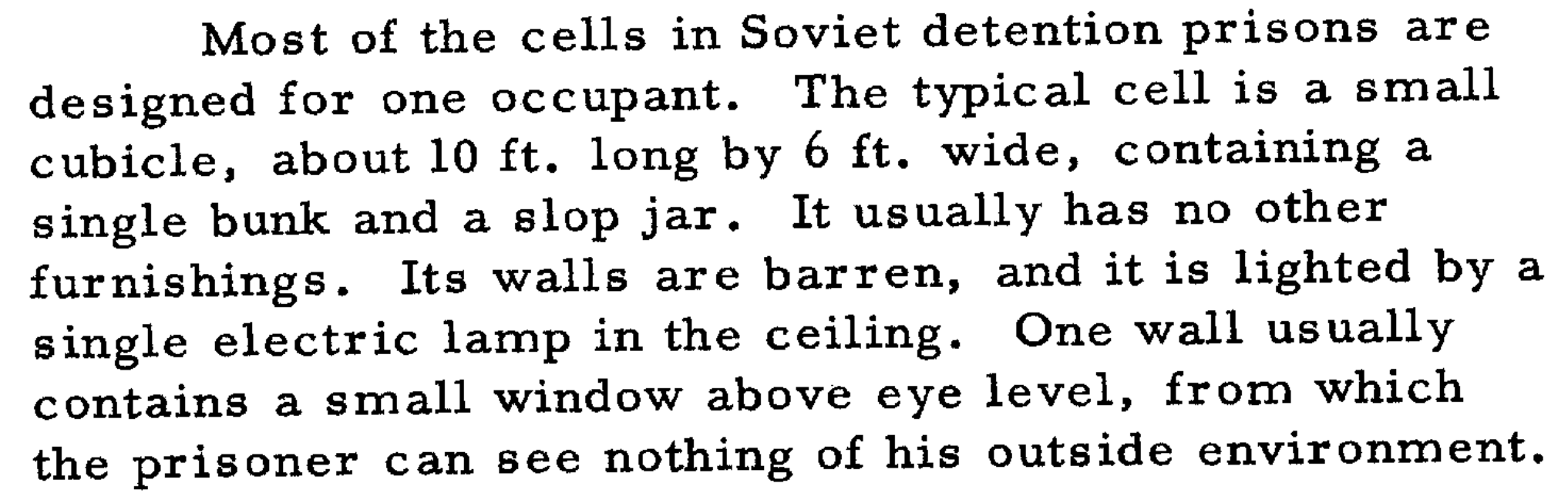

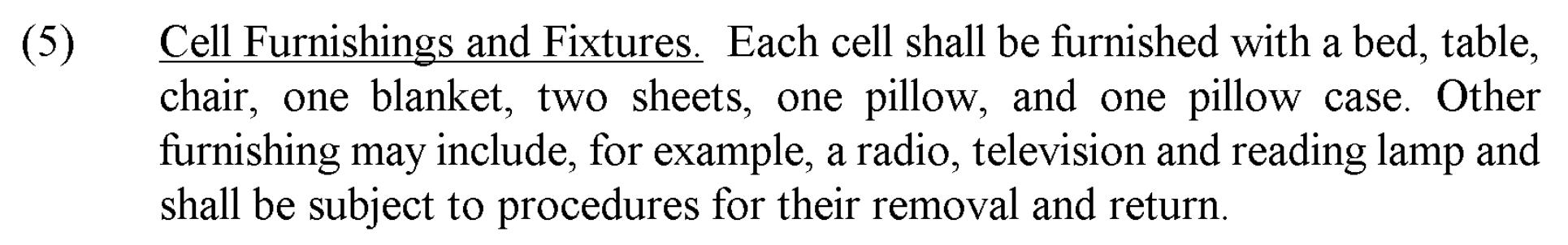

Once enemies of the Soviet state were detained, they were restricted to cells and schedules that closely resemble those of incarcerated people in US correctional facilities, particularly solitary confinement.

Compare this description of detention cell in the Soviet Union …

with this description of a “Department Segregation Unit” in Massachusetts

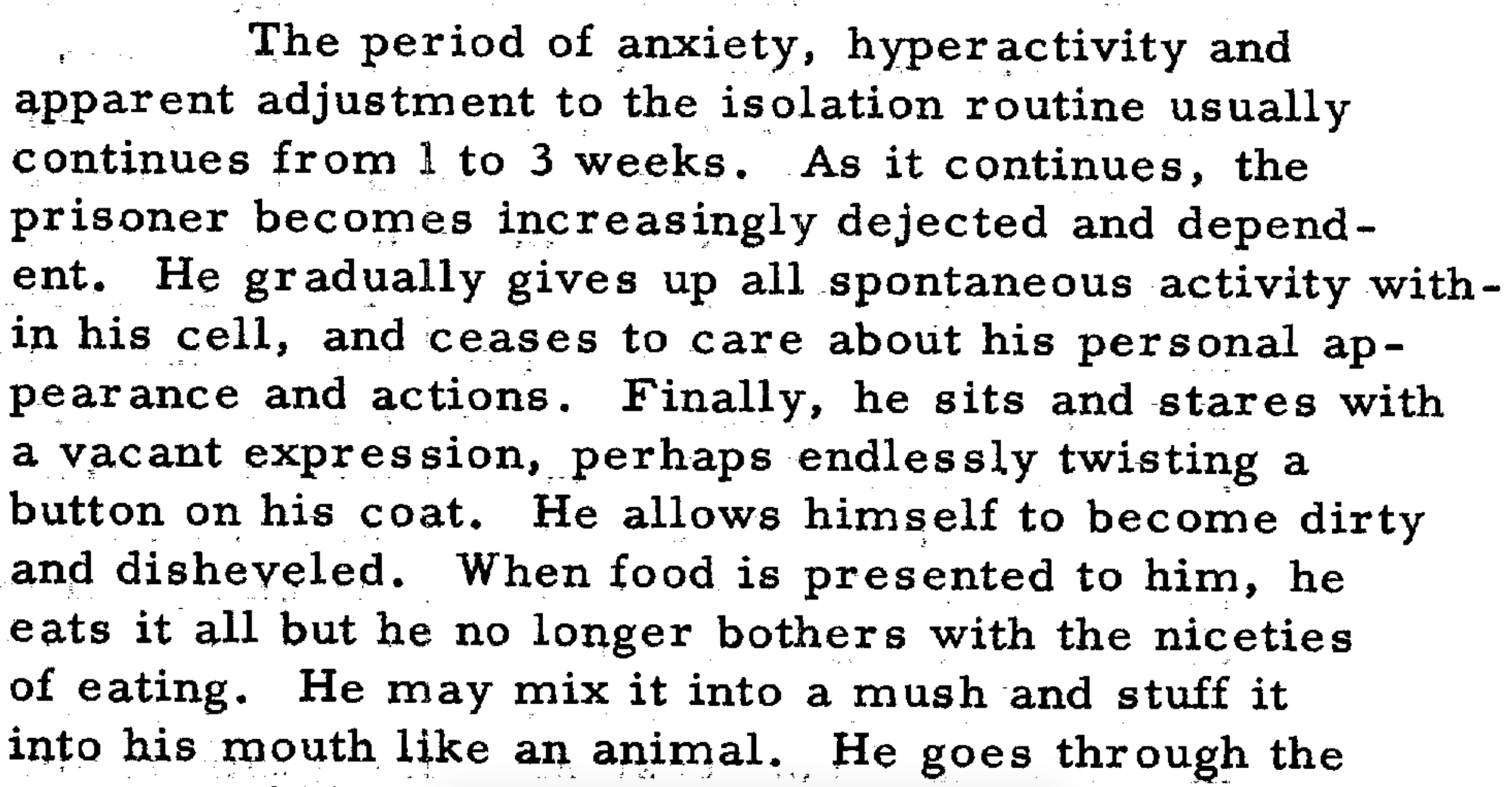

In the long term, the CIA noted, people in isolated cells developed what was referred to as “disease syndrome,” which consisted of a series of symptoms including anxiety, depression, “animal” behavior, and psychosis.

The concerns indicated by the CIA in its 1956 report mirror those of mental health specialists and criminal justice reform advocates who condemn the use of solitary confinement because its practice has proven to cause trauma and exacerbate existing mental illness.

For people suffering from mental illness in Soviet prisons, treatment was accessible, but once they became stable again, they would immediately return to structured time in isolation, which science now proves likely contributed to their initial “disturbed behavior.”

Because there is a constant demand for psychiatric beds in American correctional facilities due to the current criminalization of mental illness, people who are “rehabilitated” are forced to return to the general population. This phenomenon sets into motion a revolving door whereby mental health patients in prison do not receive necessary long term care.

5. Prison labor

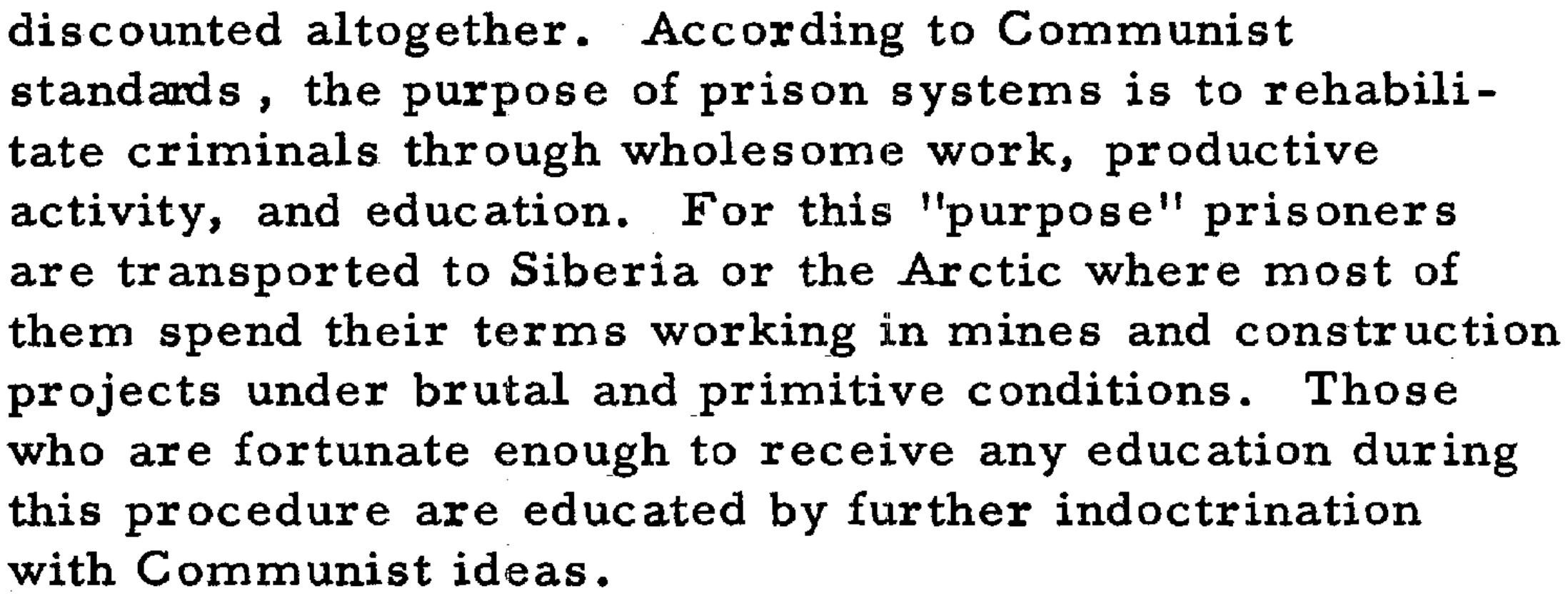

On paper, the role of the criminal justice system in the Soviet Union and United States was to “rehabilitate” its incarcerated people. But notably, both states economically benefited from its rehabilitation programs.

According to the CIA report, the Soviet Union used its incarcerated people as free labor, subjecting them to harsh working conditions in remote locations.

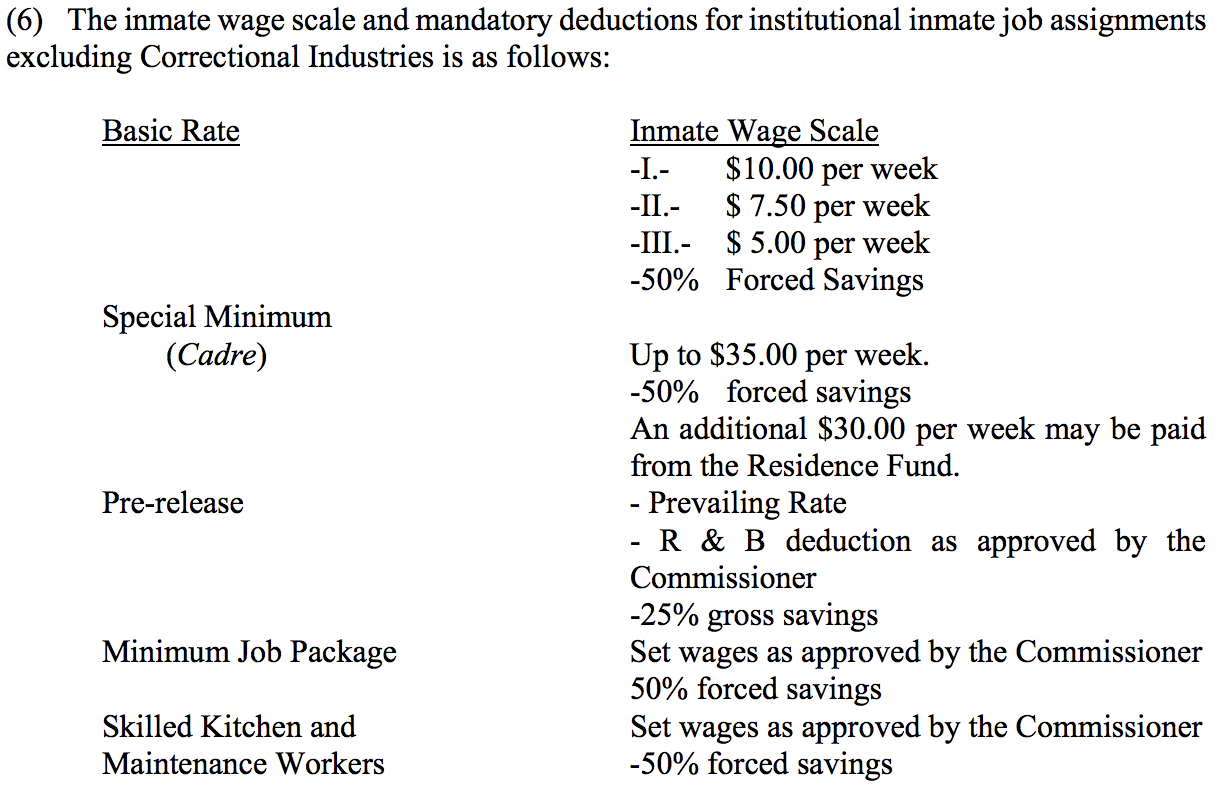

Several labor-intensive industries, such as manufacturing, in the United States benefit from cheap prison labor today. For example, in Massachusetts, correctional facilities employ their incarcerated people for minimal pay, and other affiliated work programs have the discretion to determine the pay grades of the incarcerated people they employ.

The uncomfortable irony in these parallels is perhaps best summed up in a line from a similar CIA report decrying Soviet torture techniques that would later be used at Agency “black sites”: “[there is nothing] mysterious or scientific about the Communist techniques beyond ordinary police practices that would not be condoned in a democratic country.”

That remains to be seen. Read the full CIA report embedded below.

Image via the Oregon Bureau of Land Management Flickr