One question we get asked a lot here at MuckRock is what to do in situations where an agency claims it has no responsive records when the requester knows the records exist. It comes up with frustrating frequency, and we’ve found that the root cause is often one of the five following factors.

1. The agency didn’t look

Under FOIA, agencies are required to perform a “reasonable” search for records. However, “reasonable” is a relative term, and what an agency might consider “the old college try” is more akin to a “did you even try?”

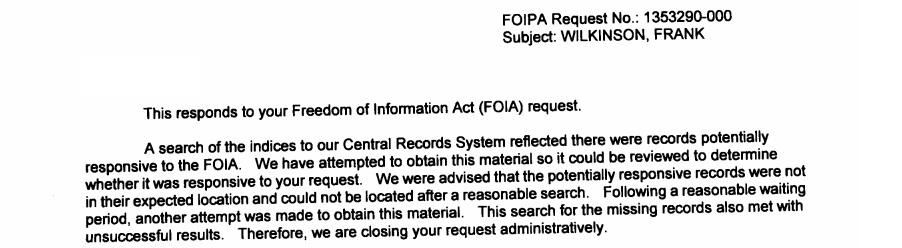

Case in point: when Emma Best first requested the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s files for the activist Frank Wilkinson - a man whose New York Times obituary devotes column space to mentioning how large his FBI file was - the Bureau’s response was apparently just to crane their neck around the room and then call it a day.

A couple years later, I discovered Best’s request while writing an article involving Wilkinson, and I filed a second request with the FBI, pointing out that finding zero pages out of a reportedly 132,000 page file didn’t fit any dictionary definition of “reasonable.” Sure enough, just a few weeks later the Bureau responded, releasing 35 pages they had just lying around and directing me to the National Archives for the remaining 131,965.

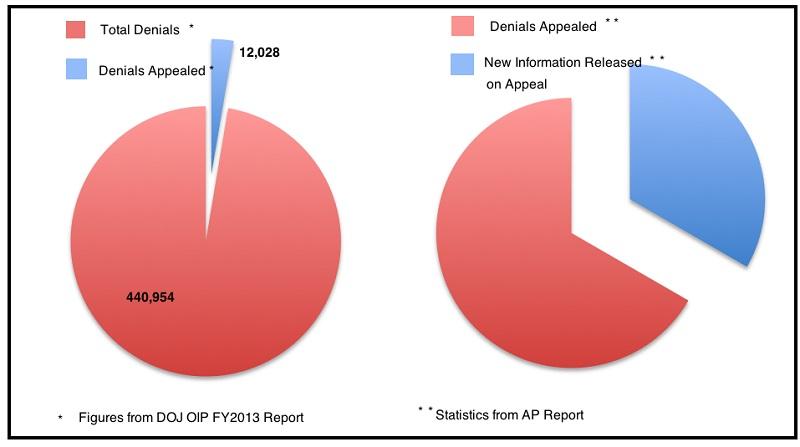

So don’t be afraid to push back if you think a response seems a little light. As the National Security Archive’s Nate Jones points out, one-third of all requests that are appealed lead to the release of more information …

which seems pretty unreasonable, when you think about it.

2. The agency didn’t know how to access the records

While the stereotype of the tech-illiterate small-town clerk has been proven false time and time again - we’ve had agencies with a few dozen people turn over thousands of records on flash drives, something we can’t get the FBI to do (and don’t even get us started on the Central Intelligence Agency’s fax machine) - every now and then you do deal with people who are incredibly polite and helpful but also can’t tell you what “metadata” is to save their lives.

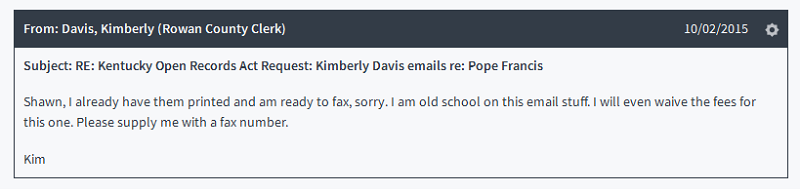

In those cases, a request that might seem simple to you (like an email search, for example) could be met with genuine befuddlement, necessitating calling in back-up from the office IT department, or, as Shawn Musgrave found himself doing with infamous Kentucky clerk Kim Davis, actually walking the clerk through the process of how to export her emails.

(In Davis’s defense, at least she tried; in Massachusetts, Braintree Police Department actually claimed that searching for emails would violate state records law on grounds it would be creating a new record.)

So when you’re starting to get the sense that the person you’re dealing with would be a lot more comfortable with a IBM Selectric than a MacBook Pro, gently suggest they pass you off to somebody a bit more tech-savvy - they’ll probably be just as relieved as you.

3. The agency didn’t know they had the records

As strange as it sounds, there have been cases where an agency might have genuinely been unaware that they had the records responsive to the request (and, yes, we are giving the agency the benefit of the doubt here).

After an April 2016 Donald Trump presidential rally in Buffalo, New York, Robert Galbraith requested related records from the local police department, including those regarding special training they had allegedly received from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. When Captain Mark Antonio responded that they had received no such training, and, therefore, no documents existed, Galbraith pointed to the source of his claim - Lieutenant Jeff Rinaldo, who had bragged to the local NBC affiliate about “working with FEMA” to “develop new protest tactics and as far as being able to handle mass demonstrations and stuff.”

Antonio, apparently a bit miffed at missing the memo, conceded that the records existed but that they were exempt under New York Freedom of Information Law. Galbraith appealed on the grounds it was kinda hard to take the word of a guy who just a few hours before was claiming he couldn’t find anything, and, lo and behold, records were released a month later.

So if you know a record exists because you’ve seen somebody from the agency loudly talk about the record existing, be sure and mention that fact. Funny how some people just need their memory jogged a bit.

4. The agency knows the records by a different name (but are still jerks)

Remember that court transcript making the rounds a few years back in which an increasingly agitated lawyer argued with a witness over what the definition of “photocopier” is, and the punchline is “Xerox?” The New York Times even made a pretty hilarious reenactment of the incident.

Well, that sort of thing happens all the time in FOIA, especially when you’re dealing with the American criminal justice system, where administrative segregation, complex detention, and intensive management are all terms for solitary confinement, a thing that by the way, doesn’t exist.

Beryl Lipton experienced a particularly egregious example of FOIA’s “evil genie” problem while requesting Immigrations and Customs Enforcement contracts related to privately-run detention centers. After being told by towns hosting the centers that no such contracts existed, Lipton pointed out there there were big buildings in the desert with Department of Homeland Security flags that they must have some sort of documentation regarding.

After much back and forth and several long, not-quite-as-funny-as-that-video-would-have-you-believe phone conversations, Lipton finally got a clerk to break and admit that while they may not have any contracts, they do have Intergovernmental Service Agreements … which is a dozen-syllable way of saying “you know, a contract.”

So learn the agency’s jargon, and be sure and ask for its subject matter listing, which is a document that lists all the types of records an agency possesses and is a great cheat sheet.

5. The agency is the New York Police Department

If you’re looking for a master’s class in the lengths an agency will go to avoid releasing the thing that it very obviously has, just look at Musgrave’s request for the NYPD’s guide to processing FOIL requests. The article’s worth reading, but short version is …

-

Agency claimed it didn’t have a FOIL guide

-

Musgrave is tipped that the guide is part of the officer’s handbook, which he then requests

-

NYPD claims of the duplication cost for the handbook will be over $500 to photocopy all 2,047 pages

-

Musgrave points out the guide is available as a smartphone app

-

NYPD settles on $15 for a digital copy.

So what’s the takeaway here? When you’re dealing with “the most transparent municipal police department in the world”, expect a headache.

Image via NBCUniversal Television Distribution