The details of the negotiations and planning surrounding the Cuban Missile Crisis have long been the subject of some contention for historians, with some of the most influential and enduring accounts contradicting what the tapes of those planning sessions tell us. Almost immediately after the Cuban Missile Crisis resolved, rumors began floating around Washington D.C. that the narrative that emerged was the handiwork of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy in an effort to force the resignation of Adlai Stevenson, Kennedy’s Ambassador to the United Nations. A Central Intelligence Agency chronology, originally classified SECRET and recently released to MuckRock, confirms that the architect of this historical revisionism was, in fact, Kennedy - and reveals that denials of this were based on nothing more than word games.

According to the declassified document, the revisionist plan went into effect less than a week after the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis on October 28th, 1962. By November 2nd, Kennedy appears to have given reporter and confidant Charles Bartlett permission to write an article about the Cuban Missile Crisis. The details of the approval, such as the original scope of the article and whose idea it was (though rumors suggest it was prompted by the White House), remain unclear despite the CIA chronology’s description of Bartlett’s repeated attempts to follow up with the Agency and push to use the access that Kennedy had apparently given him.

What the chronology does make clear is that the White House was not of one mind on the matter, and that either Kennedy had changed his mind, or there had been a disagreement or failure to communicate his permission. On November 7th, it was reported that the White House didn’t want anyone from the CIA to give an interview to Bartlett or Stewart Alsop, who was working on the article with Bartlett.

Bartlett was informed of this fact the next day, prompting him to graciously withdraw his request for an interview, saying he “didn’t want to do anything contrary to the wishes of the White House.” As the chronology makes clear, everything about the article was done with the White House’s permission.

By the next day, Alsop pushed the matter by contacting Ray Cline (a longtime contact and source of Alsop’s) and stating that the White House had apparently changed its mind.

After a couple days worth of phone tag, it was established that Alsop and Bartlett did have the President’s explicit permission to talk to the CIA for the article. Within twenty-four hours, Alsop and Bartlett sat down with Cline, who had been Agency’s chief analyst for the Cuban Missile Crisis. The interview was conducted off the record and is not disclosed in their article, though Cline is mentioned and quoted several times.

The following day, Alsop and Bartlett had meetings with both Dean Acheson and Director of Central Intelligence John McCone. According to the chronology, written by the Director’s assistant who was present, the Director argued that “it was wrong to give publicity” to the Executive Committee meetings, “particularly when it states what specific actions were recommended by specific individuals. When asked if the Agency would get to see an advance copy of the manuscript they were informed that only Kennedy would be checking it before it was submitted to the Saturday Evening Post two days later - a fact that “must not be made known to anyone.” Nevertheless, they would try to get an advanced copy of the Saturday Evening Post to the Agency.

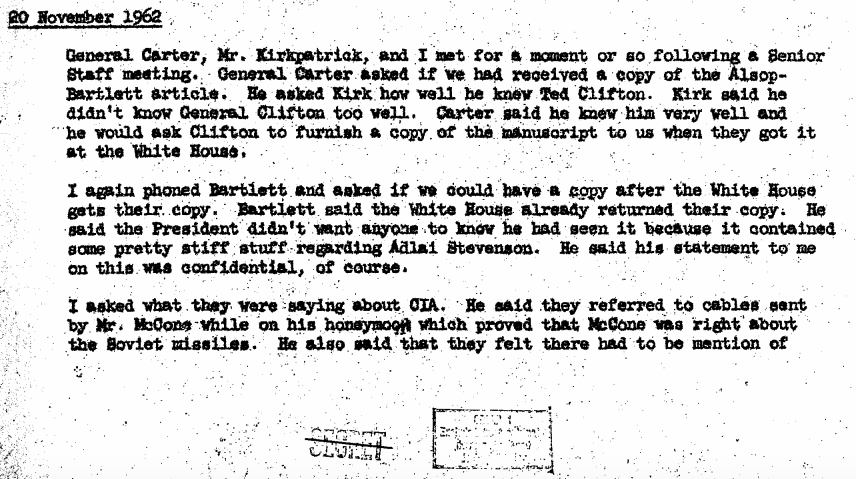

A week later, the Agency tried again to get an advanced copy of the article, only to be told that the White House had already returned their copy and that “the President didn’t want anyone to know he had seen it because it contained some pretty stiff stuff regarding Adlai Stevenson.” Bartlett also referred to a plan to address who had been responsible for the U-2 flights in a separate article, a fact that the Agency thought might cause a “flap” and “hold up to ridicule the principal people in the Air Force and SAC who have been taking bows for their splendid work in Cuba.”

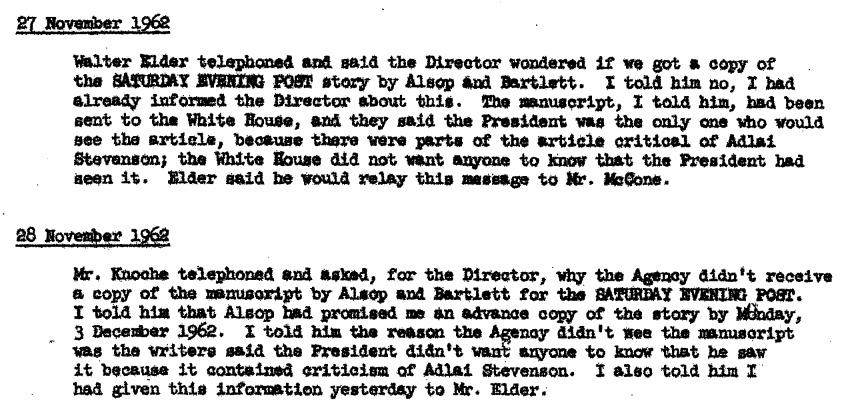

The CIA was still trying to get a copy of the article a week later, only to be reminded that “the President didn’t want anyone to know that he saw it because it contained criticism of Adlai Stevenson” and that this was the reason the Agency hadn’t seen a copy.

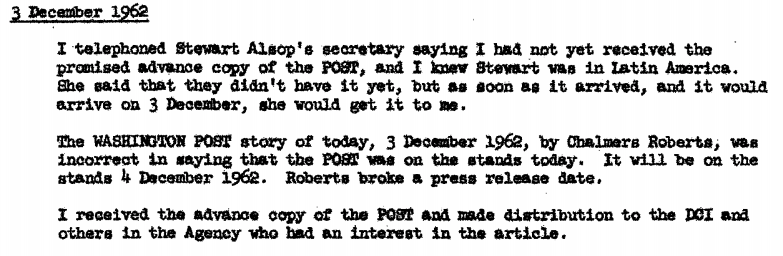

On December 3rd, the Agency was apparently still trying to get an advanced copy of the article, which was referred to in a Washington Post article which incorrectly stated it had come out on the 3rd, when it was due on the 4th (for an issue dated the 8th). That day, the Director’s office received an advanced copy of the Saturday Evening Post, which had been sent attached to a letter dated December 1st. The letter once again emphasized the article’s focus on Stevenson and his “controversial and hitherto unrevealed role … during the height of the Cuban Crisis.”

Kennedy’s exclusive role in checking and approving the article became more significant the next day, when McCone reported that the article stated things “diametrically opposed to what he told” the authors.

Kennedy’s exclusive role in checking and approving the article became more significant the next day, when McCone reported that the article stated things “diametrically opposed to what he told” the authors.

Within a week, rumors were flying around Washington about the purpose of the article. Some were already speculating that the authors had been chosen by Kennedy because of his close relationship with them, and that the goal had been to force the resignation of Stevenson. In what may have been the first article to articulate this theory about “The Adlai Stevenson Affair,” John Steele wrote:

“for weeks it was widely known in Washington that the President, specifically and directly, had charged Bartlett, an old and intimate friend … to help prepare a semi-official chronology of the events of the October crisis … On White House orders, the doors of the State Department and of the Central Intelligence Agency were thrown open to the two reporters. Neither writer talked with Stevenson,” who called it a “classic example of irresponsible journalism.”

The CIA quickly reacted to the article (dated December 14th) after the Washington Post referred to it on the 10th. The Agency’s response to the article was to deflect from Kennedy’s role in the article, specifically by focusing on the phrase “White House orders.” According to the chronology, the Director’s office planned to deny the article’s accuracy by saying “there were no White House orders for CIA to see anyone.” [emphasis in original] This amounted to little more than semantics, as the White House had specifically granted permission to speak with Kennedy’s close friend about the matter, after which Kennedy would read and approve the article. This sort of denial was akin to a child arguing that they hadn’t been told to clean their room because a caretaker had simply said they wanted it done. While it may be true that there was no direct order, the distinction is disingenuous and largely irrelevant.

The article’s effects were long lasting, and went beyond an attempt to force Stevenson to resign. The article went from being a “semi-official” history to one that was virtually authoritative, even being extensively relied upon and quoted in seminar’s on American foreign policy that the Agency would incorporate into its files. The effect of the article, which contradicted what the authors had been told by the CIA Director, was to rehabilitate the position taken by Attorney General Robert Kennedy at the expense of his UN Ambassador, as Sheldon Stern explained.

According to Stern, who served as historian at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum from 1977 to 1999, the article recast Robert Kennedy as the “leading dove” of the debate - a position that, after the crisis ended, the Kennedys’ discovered would be more politically useful to them. As Stern explained, the tape recordings of the National Security Council meetings not only fail to show Robert Kennedy as a “leading dove” in the debate, they show him taking a “hawkish, even reckless, stance during the meetings, pushing for a tough strategy that would remove Fidel Castro and demonstrate American resolve to the Soviets.”

Decades later, another attempt was made to reframe the Kennedys as “doves” in the matter. In 1987, after everyone else involved was long dead, Dean Rusk penned a letter that claimed President Kennedy had secretly developed a plan that was a virtual mirror of Stevenson’s. According to Stern, Stevenson “was the first to propose a trade of the Cuban and Turkish missiles, and stood his ground against harsh criticism from ExComm’s hawkish majority. It is ironic, of course, that the proposal Stevenson advanced on October 26 was nearly identical to the one JFK secretly adopted the very next day.” This plan was reportedly proposed to the Soviets by Robert Kennedy the next day, despite his “hawkish and even reckless” advocacy during the NSC meetings. According to Rusk, only he, President Kennedy and Andrew Cordier were aware of the plan, which Rusk later dismissed as “not all that much of a big deal; it was simply an option that would have been available to President Kennedy had he wanted to use it.”

If such a plan did exist, it makes Kennedy’s attack on Stevenson all the more extreme. If it didn’t, it adds to the revisionism and attempts to make the Kennedys into “doves” that advocated peaceful negotiations rather than airstrikes or an invasion of Cuba. Regardless of whether or not Rusk’s letter was accurate (though it has been widely accepted as so by historians, including Stern), the newly released CIA chronology solves what the New York Times described as a decades old mystery about the virulence and source of the public attack on Stevenson by firmly ascribing the article to the President, who was the only person to review it prior to submission, a fact he wanted concealed precisely because of its attacks on Stevenson

You can read the Saturday Evening Post article here, Stern’s analysis of the events here, or the declassified chronology below, or on the request page.

Image via JFK Presidential Library