Mykola Lebed was sentenced to death in Poland in 1934. He died in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1998.

By various accounts, he was an assassin, a freedom fighter, a terrorist, a hero, a villain, a prisoner, a refugee, a Nazi collaborator, a Nazi target, a writer, and a war criminal. To the Central Intelligence Agency, which bankrolled his activities for close to half a century, he was known as “Uncle Louie.”

Lebed was one of the leaders of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. Referred to by some as a terrorist group and by others as freedom fighters, the OUN and its subsidiaries were accused not only of political assassinations in Poland, but also of ethnic cleansing in Ukraine during the mid-20th century.

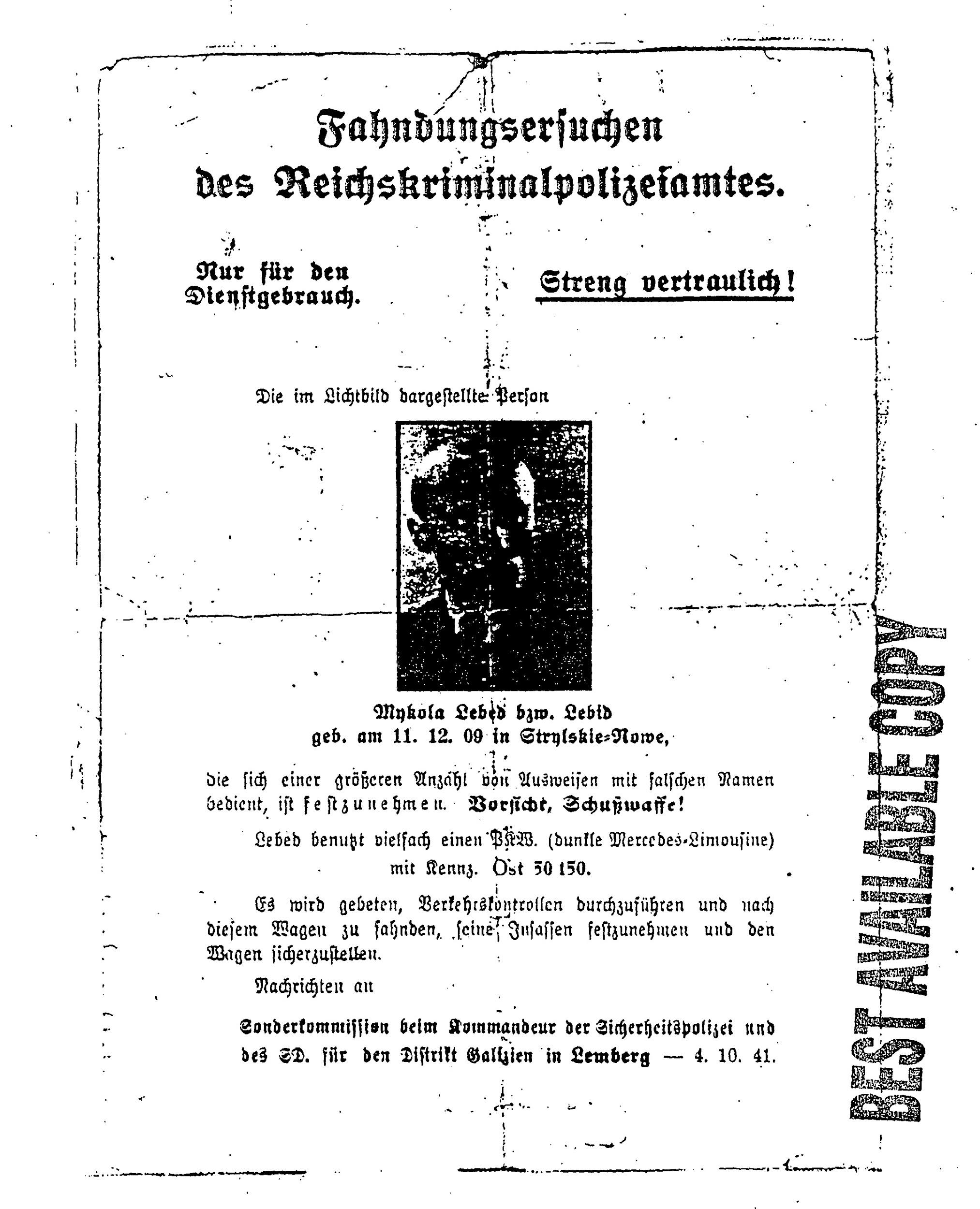

In 1934, along with several other OUN members, Lebed was sentenced to death for the murder of Polish official Bronisław Pieracki. The sentence was commuted in 1936 to lifetime imprisonment, and Lebed managed to escape prison during the the German invasion of Poland in 1939.

In 1940, The OUN split into two factions: the OUN-B for loyalists of Stepan Bandera, and the OUN-M for followers of Andrei Melnik. Lebed was a leader of the Bandera group.

Both factions of the OUN sided with the Nazis to some extent. Melnik aimed to be friendly with the Nazis in hopes that after the war Ukraine would emerge an independent nation. Bandera was more keen on forcefully creating an ethnically homogenous, independent Ukrainian state with himself as the leader of it.

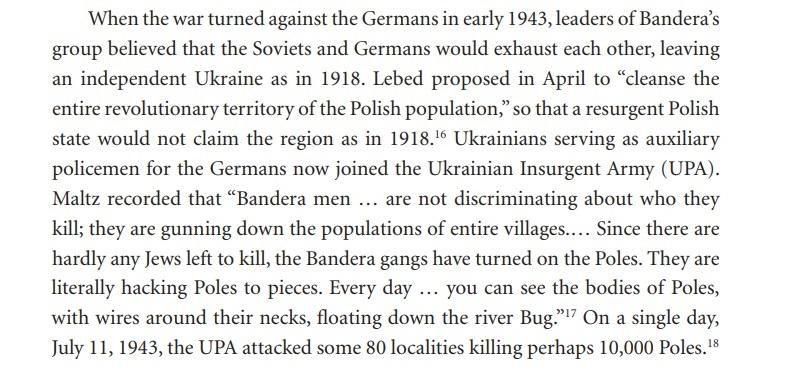

By most accounts, OUN collaboration with the Nazis was opportunistic. They were groups at odds, but had a perceived common enemy. The OUN’s determination for an ethnically Ukrainian nation was not dissimilar to Nazi ideology, insofar as both aimed to remove ethnically Jewish and Polish people from their communities. Both were willing to obtain that objective by any means necessary, be it forced relocation or murder.

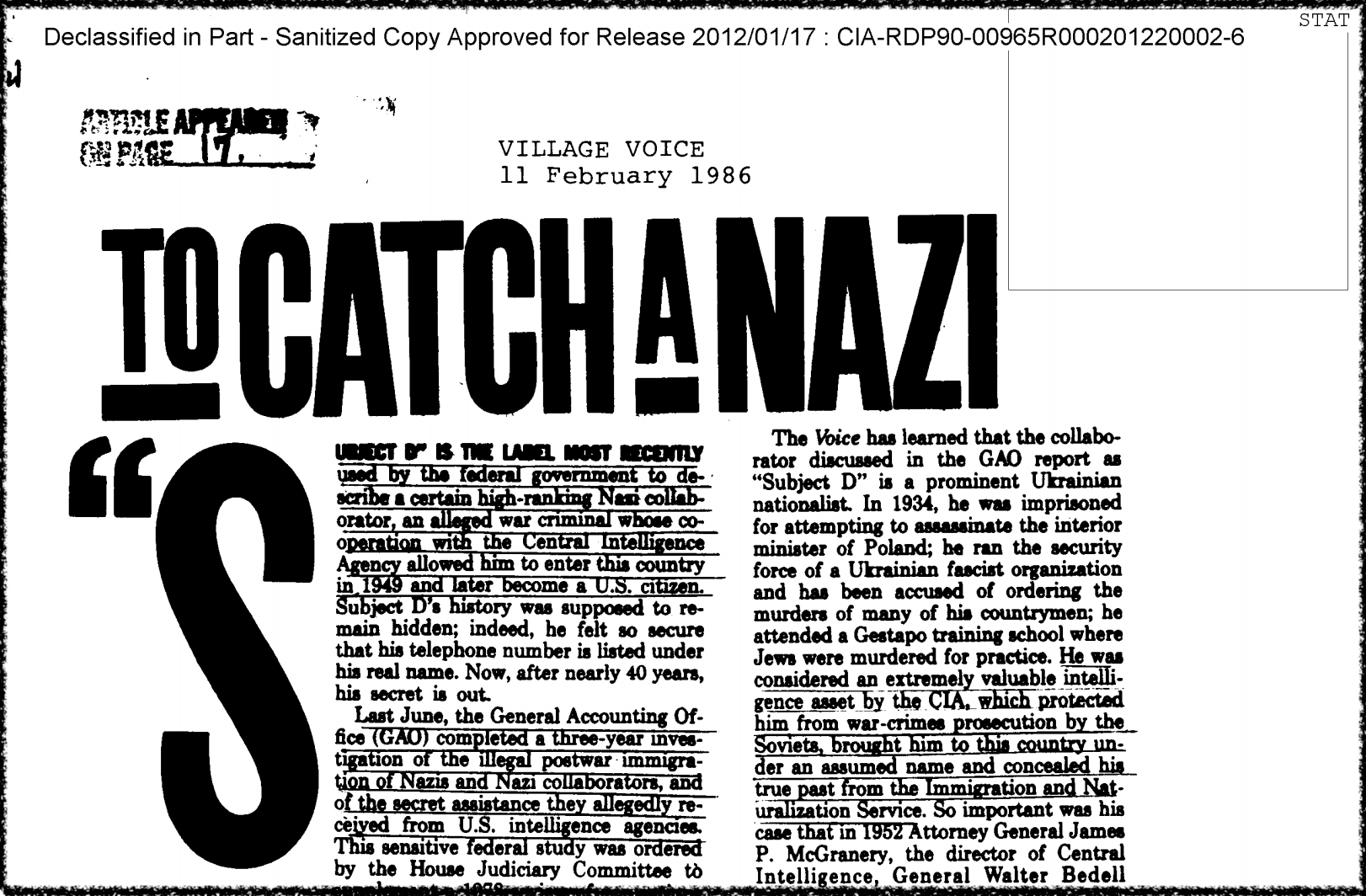

After his escape from prison, Lebed trained at a Gestapo police school in Zakopane. Exactly how long he spent there is unknown. Lebed admitted to being at Zakopane for about five weeks, but other accounts place him there for several months.

“From Krakow, still on instructions from [an OUN Leadership Council] member, I went to another rest camp in Zakopane. Discovering on the spot that this “rest camp” was under the control of the German police, and that it was to be converted into a police school, I left it, freeing at the same time from camp control a group of people, using various pretexts,” Lebed declared in a 1952 questionnaire.

While Lebed described his actions at Zakopane as almost heroic, a fellow trainee recalled Lebed’s behaviour at Zakopane much differently. A 1986 Village Voice article relayed Mykyta Kosakivs’kyy’s account of Lebed enthusiastically kidnapping and torturing a man as part of his training.

The Nazis sent Bandera to Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1942 after he declared Ukraine an independent state. Lebed became the de facto leader of the Bandera faction, which largely controlled the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), through the end of the war. Over the following few years, the UPA was responsible for tens of thousands of murders.

After the end of World War II, Western intelligence agencies sought to acquire OUN members as informants and infiltrators. The OUN was avowedly anti-Communist, and it already had a network of trained guerilla fighters at the ready for an anticipated Soviet offensive.

The United Kingdom’s MI6, their analogue to the CIA, opted to work with the Bandera, who later died under mysterious circumstances, allegedly murdered by the KGB.

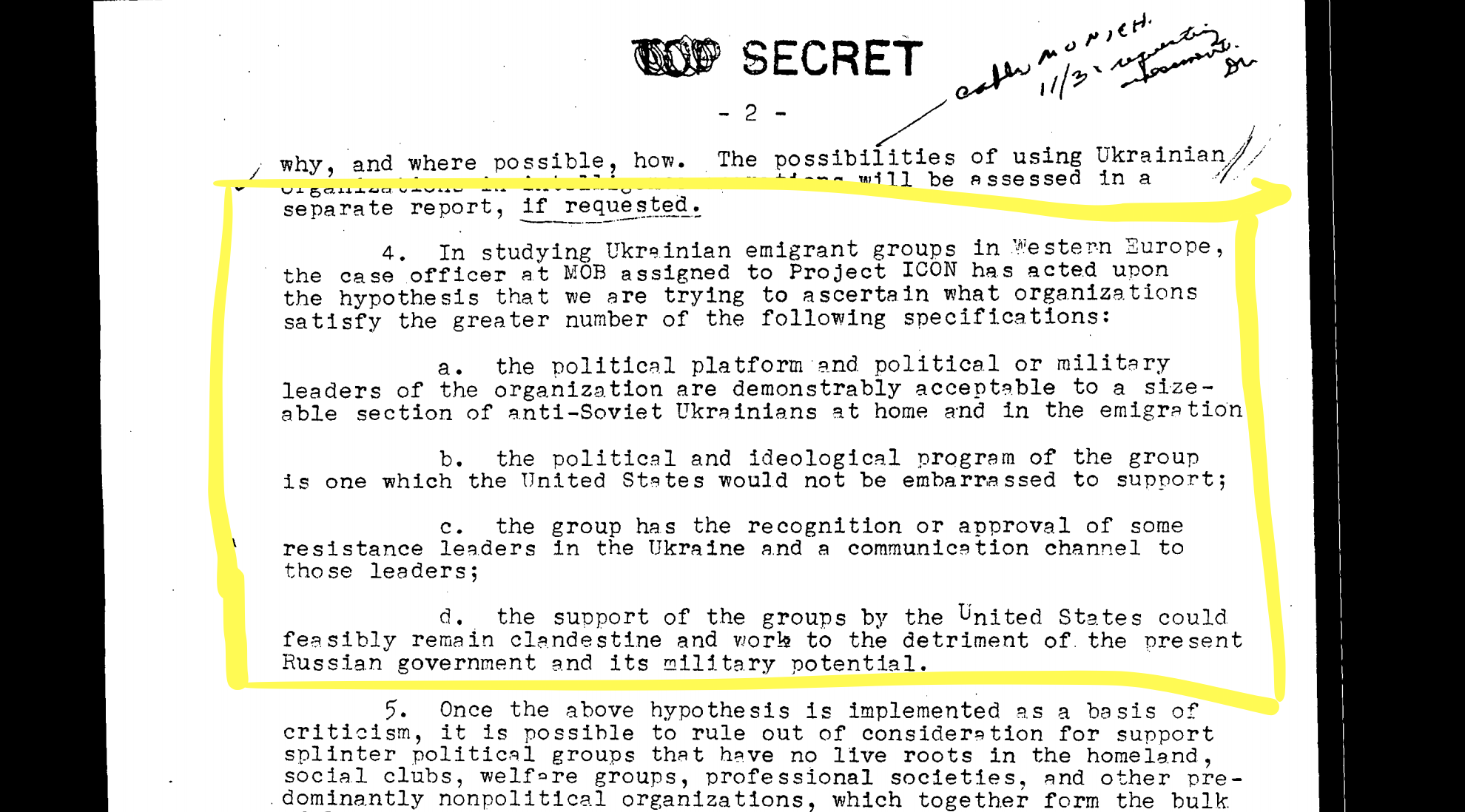

The CIA chose to work with Lebed, then the Foreign Minister of the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council (UHVR). Lebed still had considerable influence among Ukrainian nationalists. Bandera was too extreme and his following, the CIA concluded, was dwindling.

The early CIA accounts of Lebed reveal the agency believed he and his comrades were “determined and able men, but with the psychology of the hunted … resolved to carry on their work with or without us, and If necessary against us.”

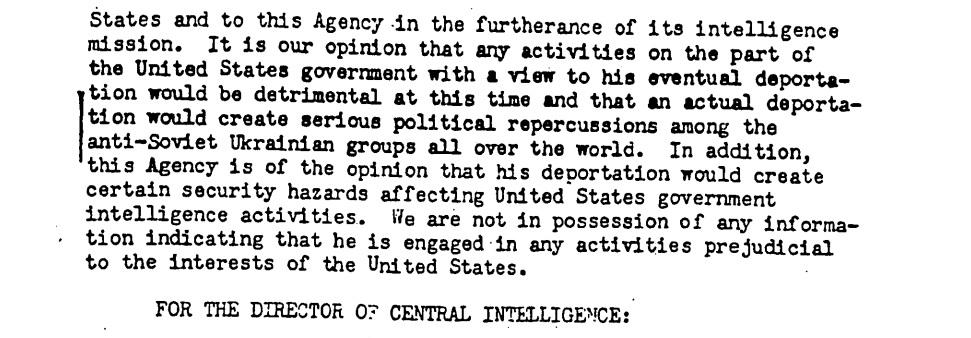

The CIA knew early on of Lebed’s conviction for assassination, his training at Zakopane, and his one-time control over the OUN-B, but documents show the agency believed it to be lies peddled by Soviets or Melnik loyalists. Later, the CIA shielded Lebed from allegations and deportation because he was too valuable of an asset and any publicity could compromise the entire project

.

The CIA’s defense of Lebed essentially boiled down to that Lebed was never a member of the Nazi party. But, Lebed had a complex history. While the reports that Lebed was a Nazi were likely incorrect (technically), and indeed, there was at one point a Nazi warrant for his arrest …

but in one of the CIA’s own hair-splitting denials that Lebed was a Nazi, it admits that Lebed was the top leader of the “anti-soviet Ukrainian resistance movement” during some of its most violent time - a time when swaths ethically non-Ukrainian populations were systematically murdered by that movement’s proponents.

Lebed was perhaps not a member of the Nazi party, but by many accounts he espoused the values of Nazism.

Among the criteria used in the CIA’s analysis of various Ukrainian groups were that “the support of the groups by the United States could feasibly remain clandestine and work to the detriment of the present Russian government and its military potential” and that “the political and ideological program of the group is one which the United States would not be embarrassed to support.”

Lebed fit the bill, a report concluded.

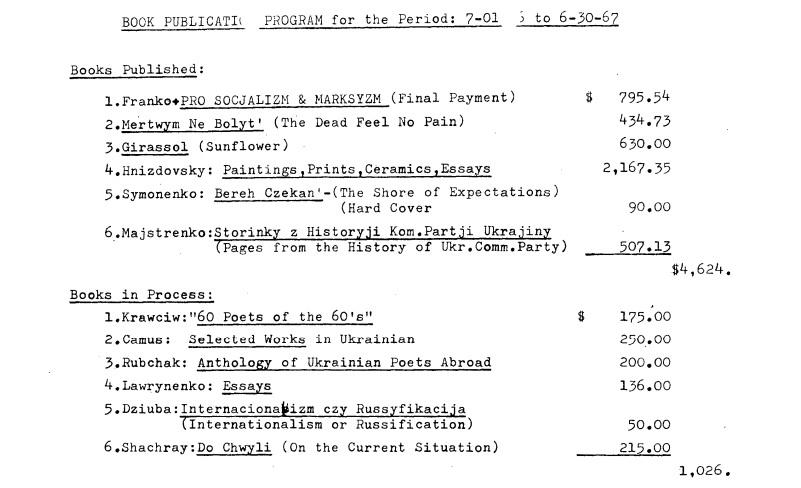

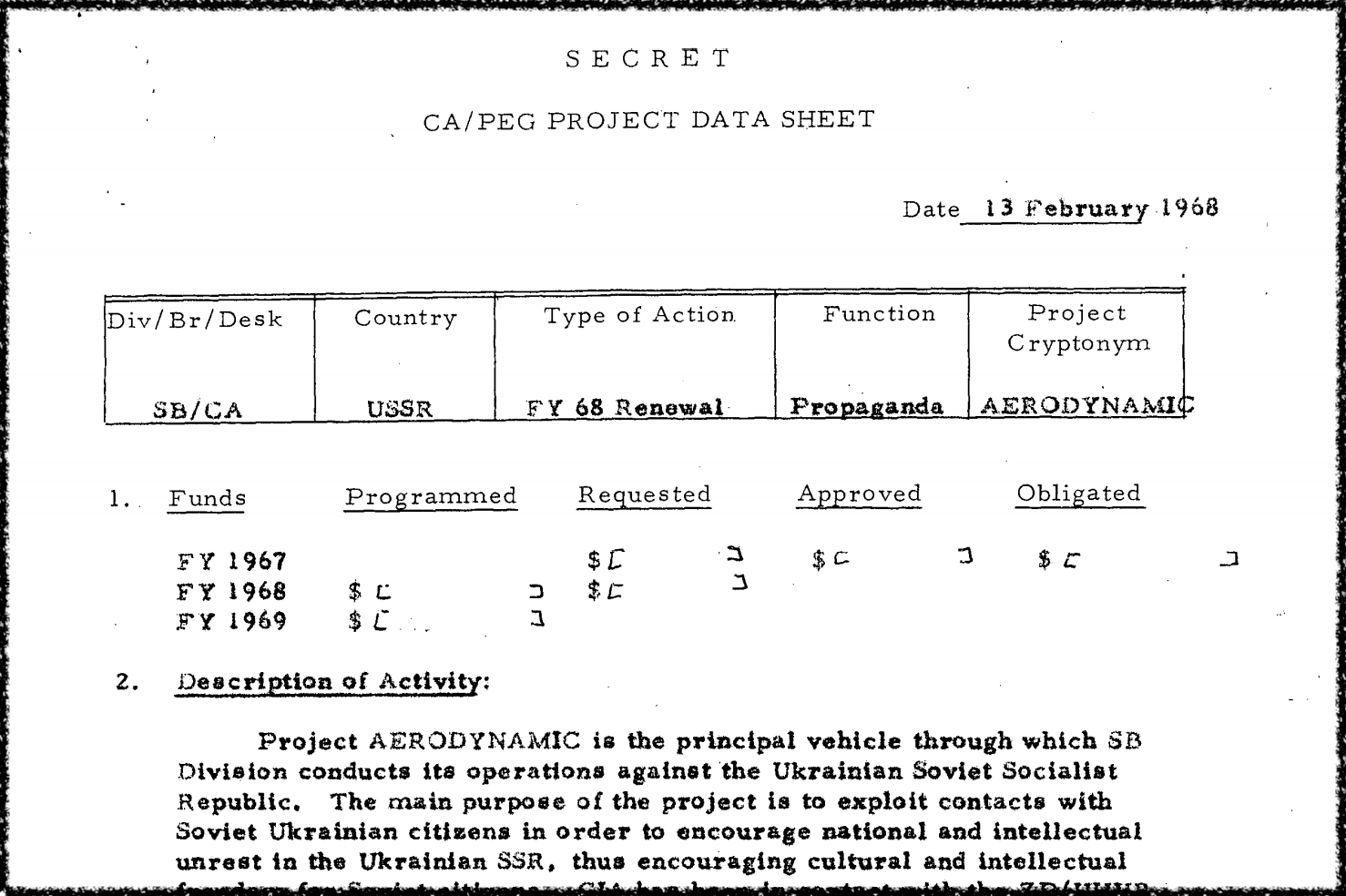

The CIA facilitated Lebed’s move to the US, getting asylum for him and his family in 1949 and helping him obtain citizenship in 1957. As head of a CIA operation called Project AERODYNAMIC, Lebed spent the next few decades in control of a Agency-funded non-profit publishing company, the Prolog Research and Publishing Association.

His salary at that company in 1967, for example, was $11,970. That’s roughly equivalent to $91,700 in today’s terms according to the Bureau of Labor and Statistics. His job was to spread anti-Soviet, anti-Communist propaganda in Ukraine.

However, some publications were also distributed within the US - a knowing violation of laws against domestic distribution of propaganda.

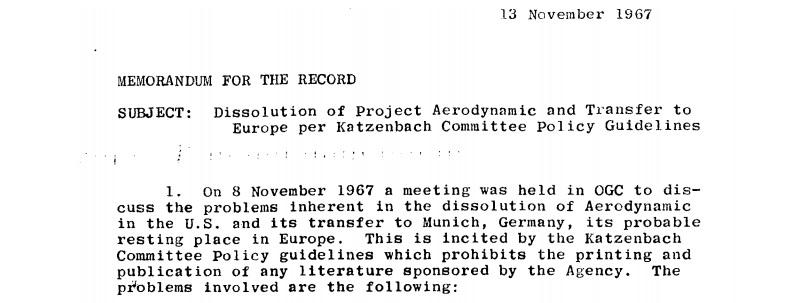

Prolog Research and Publishing Association reincorporated in 1967 as a for-profit named the Prolog Research Corporation. The reorganization was in response to new regulations introduced by the Katzenbach Committee, according to an agency memorandum.

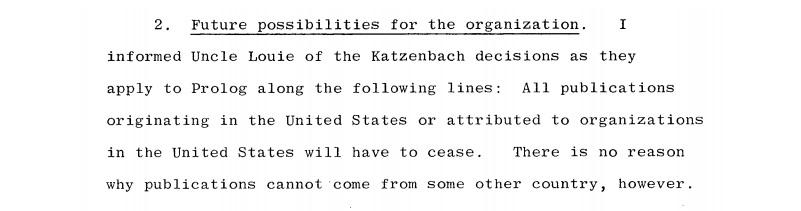

Although the policy recommended by the committee were specifically aimed at prohibiting the kind of work done by Lebed and Project AERODYNAMIC, the CIA quickly discovered a loophole - the publications could be printed somewhere other than on US soil.

(This wouldn’t be the last time the Agency would “terminate” a program, only to move it abroad.)

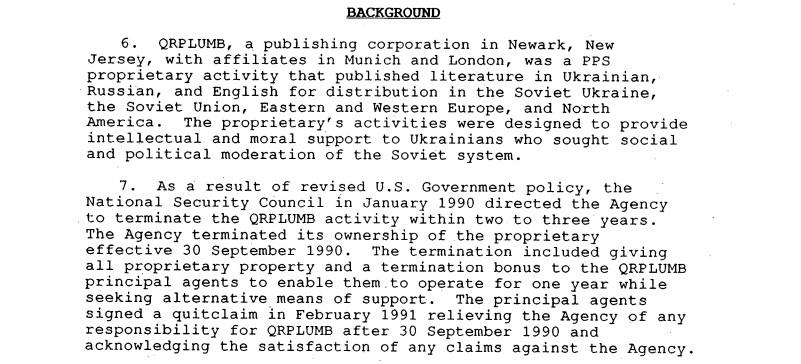

Project AERODYNAMIC was dissolved and its front company, Prolog Research and Publishing Association, shut down. But the self-described propaganda campaign continued under the new names QRDYNAMIC and Prolog Research Corporation.

Despite the turmoil for the Agency in the ‘70s caused by the Church and Pike Committees, Lebed and QRDYNAMIC continued their work throughout the decade without incident. When trouble did come, however, it came from an unlikely source - the famously CIA-friendly Reagan administration.

Often credited for the expansion of government surveillance and data collection, President Ronald Reagan’s Executive Order 12333 in 1981 also added regulations regarding how intelligence agencies can influence entities within the US.

The order states that “no one acting on behalf of agencies within the Intelligence Community may join or otherwise participate in any organization in the United States on behalf of any agency within the Intelligence Community without disclosing his intelligence affiliation to appropriate officials of the organization. … No such participation may be undertaken for the purpose of influencing the activity of the organization or its members [with a few exceptions].”

An audit of QRPLUMB, a cryptonym of Prolog, concluded in 1991 that the project had violated E.O. 12333 by distributing CIA-funded propaganda in the US. Among the 24 U.S.-based subscribers acknowledged in the audit and contemporary internal communications were “Harvard and some Ukrainian church-affiliated groups.”

The auditors made no suggestion to remedy to problem: “QRPLUMB was terminated 30 September 1990; therefore, we are not making any recommendations concerning QRPLUMB.”

(This was not the first time the Agency would escape consequences for engaging in illegal activities.)

Possibly driven by widespread press criticism in the mid-’80s, QRDYNAMIC officially ended in 1990 (though some accounts claim it ran through 1991), and Lebed died eight years later,

You can explore his nearly 50 years of association with the Agency via the timeline below.