With the recent launch of both our book of Federal Bureau of Investigation files and a crowdsourced effort to analyze Ronald Reagan’s 30,000-page file, we thought it would be the perfect time to answer one of the most frequently asked questions we get here at MuckRock: How do you even begin to tackle these huge releases?

This is intended as an introductory guide, and, as such, we won’t be going into the intricacies of the Bureau’s filing system, such as common forms and offense codes. That article will be coming down the line, and in the meantime, we can recommend Phil Lapsley’s article at the Mary Ferrell Foundation and Gerald Haines and David Langbart’s excellent book Unlocking the Files of the FBI: A Guide to Its Records and Classification System.

1. Don’t be intimidated!

Let’s say you filed a request for an FBI file through MuckRock. After months of anticipation, you finally get the email you’ve been waiting for since you clicked that blue “submit” button - your request is completed, and the Bureau’s enclosed thousands of pages. You head on over to the request page, and you’re hit with this:

So many numbers! Where to even begin? And why are the files split up in such an arbitrary way? Wouldn’t just numbering them consecutively make more sense???

Okay, first, don’t panic, and second, yes, that would make a lot of sense, if the Bureau wanted to make these files accessible to the general public. We can toss that assumption right out the window.

When it comes to where to start, my personal philosophy is: Wherever you feel like. These files can be daunting, but it’s important to remember that there’s no wrong way to do this (with an important caveat we’ll address later) - these files belong to you, and if you don’t read them, nobody else will. By just picking a random page from a random file, you’re doing your part to reclaim a history that has been hidden away, if not outright stolen. Beside, a bulk of these files are the mid-century equivalent of office email, and how good are you at reading office emails? So good!

Alright, let’s practice what we preach by pulling up a random page from a random file in the Reagan crowdsource, which you can do via the button below. Open in a new tab or window if you want to keep reading along.

All set? Continue not panicking, and let’s ask a few questions.

2. What are you looking at?

Alright, so what do we got? Broadly, individual records from FBI files break down into a few general categories, which we’re using as one of the fields in the Reagan crowdsource.

Background Checks

These are routine investigations preformed by the Bureau ahead of appointment to a sensitive position, typically presidential committees, and consist of credit and criminal checks and some character interviews. Here’s a request for a background check on the author Tom Clancy …

that, incidentally, ended up turning up Clancy’s awful college GPA.

Interviews

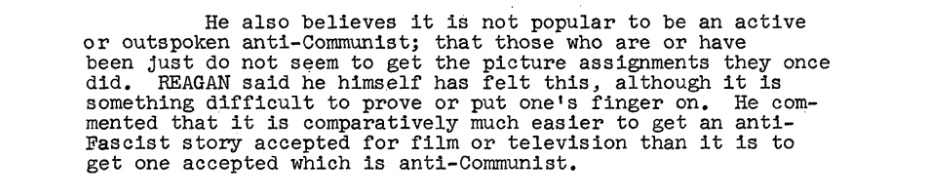

The Bureau spends a lot of time talking to people, and those conversations end up summarized in the file. Here’s an agent chatting with Reagan about anti-anti-Communist bias in Hollywood:

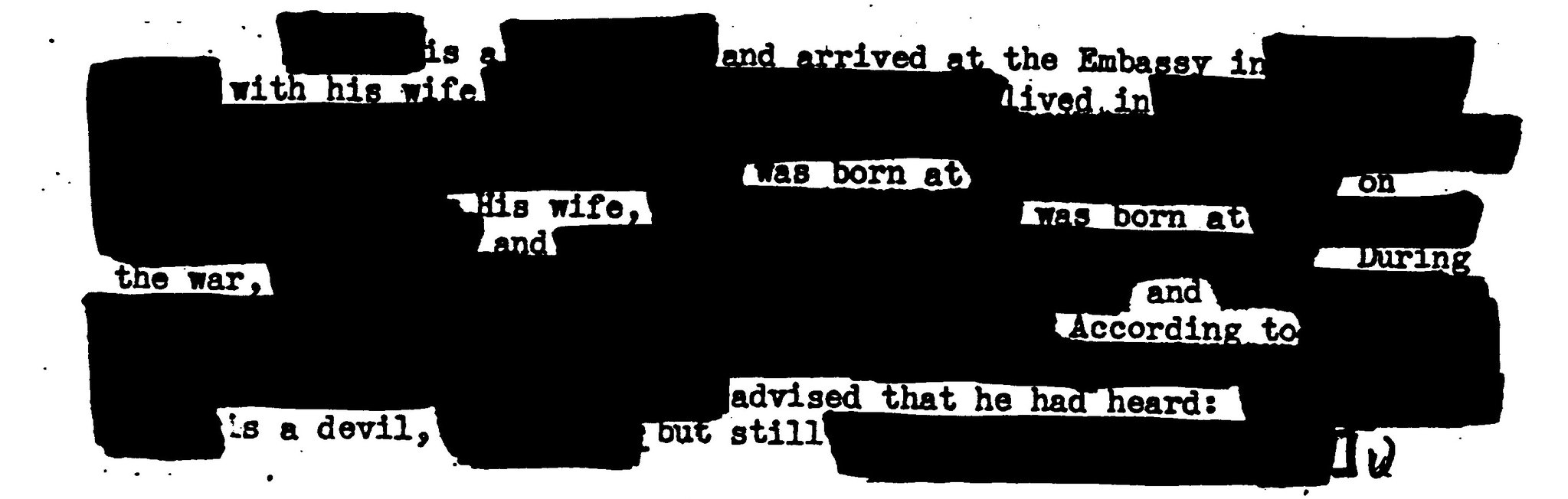

Some of those interviews, however, are with confidential sources, and those interviews are about confidential things - so you get something like this:

That said, with enough context, you can sometimes suss out who the Bureau was chatting with, heavily redacted or not, so just knowing that there was an interview on that day helps.

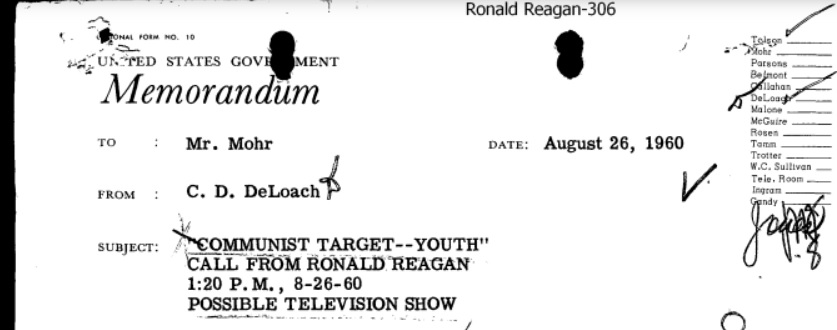

Letters

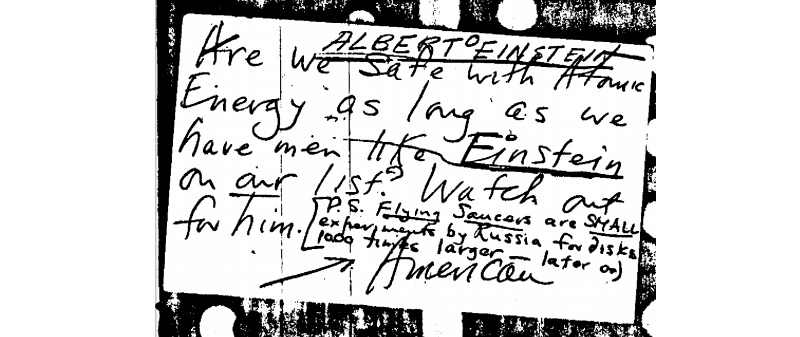

The FBI got a lot of mail, whether it be anonymous tips about Albert Einstein …

or inquiries about Nikola Tesla’s “death ray”:

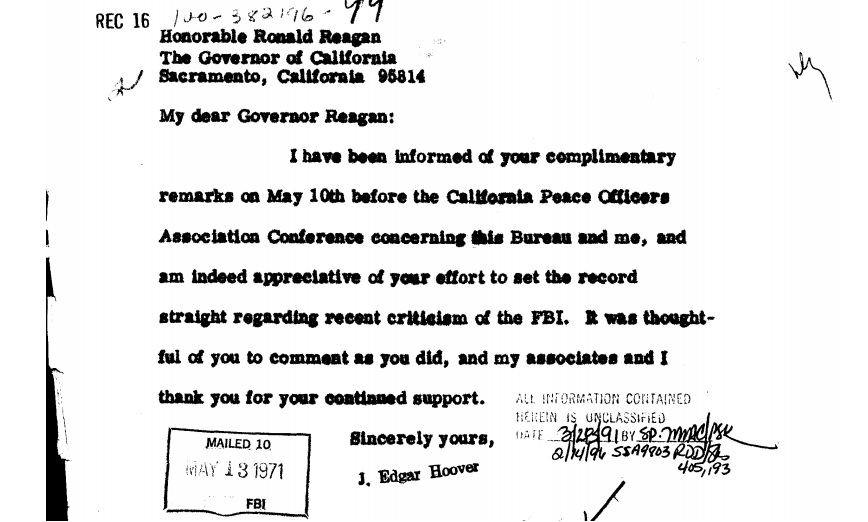

The correspondence of FBI Directors, particularly J. Edgar Hoover, also ended up in the files, such as this expression of mutual admiration from Hoover to Reagan.

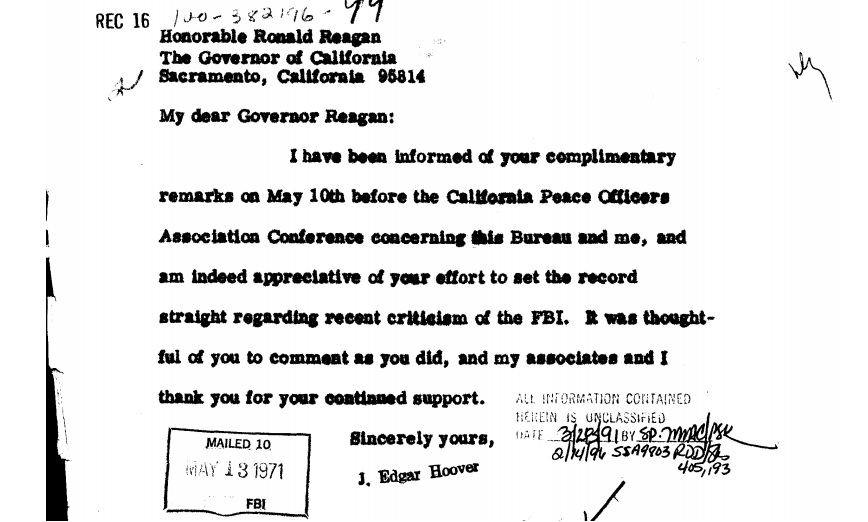

Memos

These are those office emails we alluded to earlier. To give a rough estimate, a bit over half of all FBI files are comprised of these memos and their equivalents, such as “Airtels.” Fortunately, they’re also the most straightforward - just like an email, you’ve got sender, recipient, subject, date - all that good stuff.

Also like emails, there’s a lot of information crammed into the footer that you’re used to just skimming over, which is a good thing to keep in mind once you’ve gotten the hang of a particular file and you’re looking for more leads.

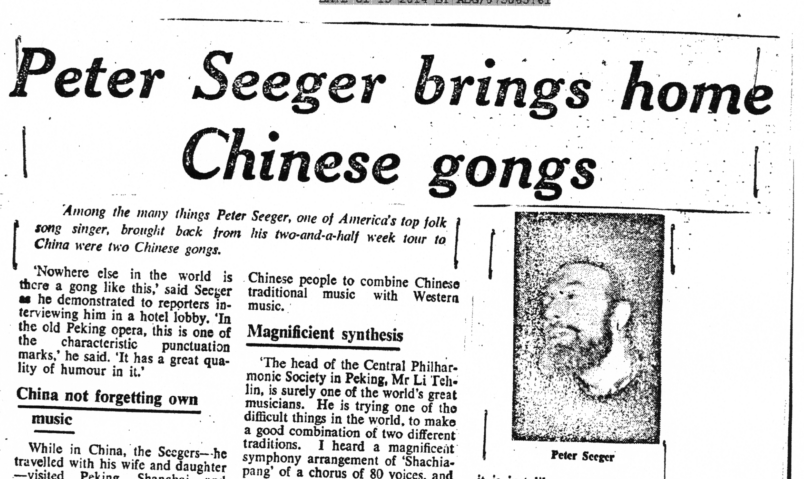

Press Clippings

Like any other intelligence agency, the Bureau relies a great deal on open source intelligence gathering - which is a fancy way of saying they read the news. Expect to find a lot of old newspaper and magazines articles in the files - even on topics as dubiously relevant to the safety of the republic as Pete Seeger’s gong-purchasing spree. .

You’ll also see a lot of coverage of the FBI itself. Hoover was notoriously sensitive to criticism and had a team of agents spread out over the country tasked with clipping any articles in the local press which mentioned him or the Bureau …

which we know about because a clipping of an article that mentioned it ended up in his personal FBI file.

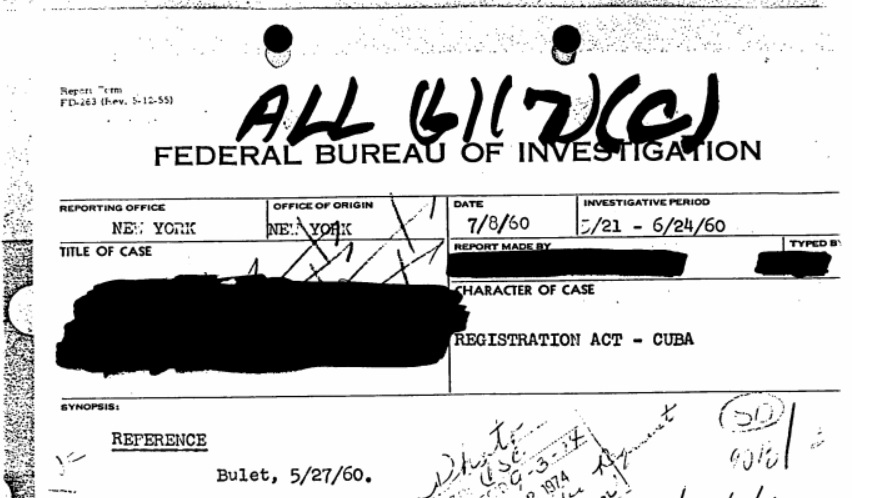

Reports

Throughout the course of an investigation the Bureau will produce multiple reports, ranging from background information on the case to interviews and interagency communications. Similar to memos, these tend to be fairly straightforward in terms of details, albeit heavy on the redactions, as seen by this example from Truman Capote’s file.

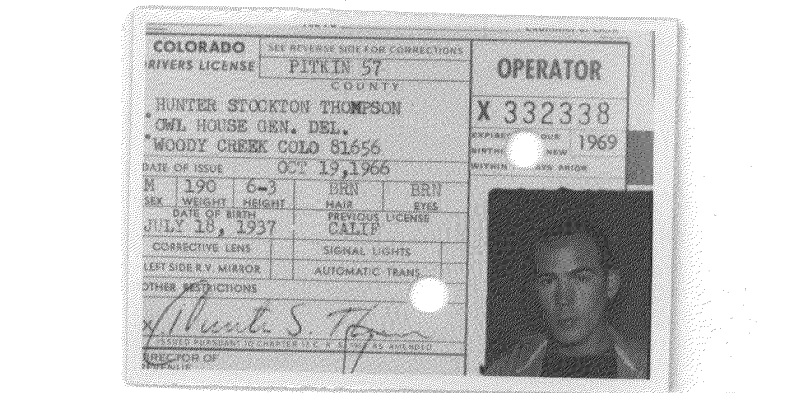

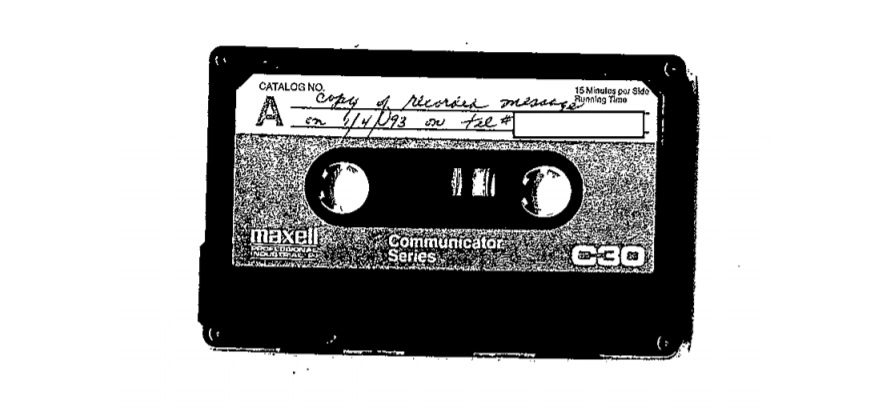

Other

Sometimes, you’ll find something that’s just plain weird. Like, say, Hunter S. Thompson’s driver’s license …

or a tape from Casey Kasem’s answering machine.

Those are fun. Let us know about those.

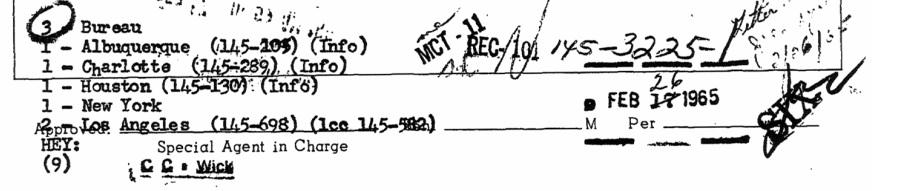

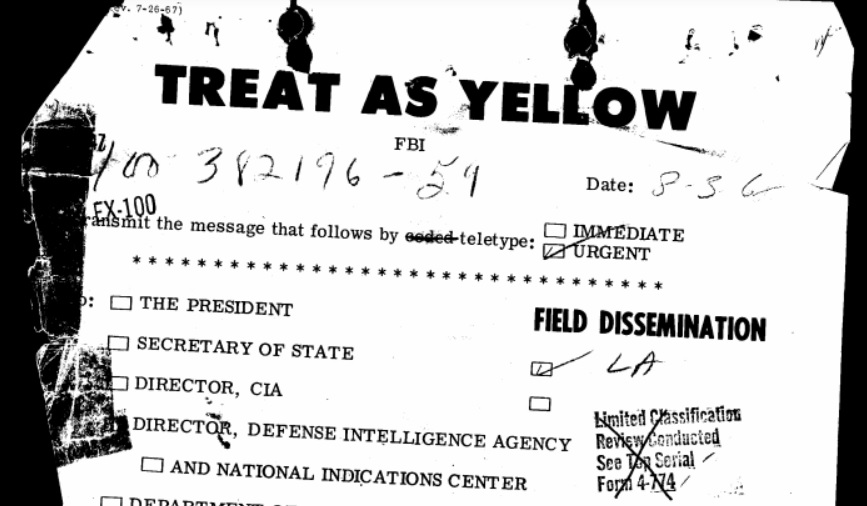

Also, the FBI puts the Bureau in bureaucracy, so you’ll see a lot of administrative material, like transfer slips:

Those are not as much fun but can be useful when you’re drilling down more details.

3. When is this from?

Once you’ve figured out what you’re looking at, it’s time to find a date. You can typically find it in the header or footer, though it’s sometimes just stamped on there.

Once you have that date, you can place the document in context, both within the file itself and the larger history of the FBI. The internal context we’ll discuss next, but regarding the larger history, that date will tell you which FBI Director was in charge, who was president, what broad social movements were happening domestically, what war was being fought abroad (both cold and hot), whether public opinion was broadly pro or anti-Bureau - you know, context. As part of the Subjects Matter FBI Files project, we’re building an interactive timeline of investigations, and being able to see what the Bureau was doing when it was doing it has been illuminating.

For example, if you take the timeline to 2003, you can see how shortly after the invasion of Iraq, the FBI opened a terrorism investigation into the Earth Liberation Front, specifically in regard to their anti-war activities. A month later, the Bureau opened a terrorism investigation into Food Not Bombs - whose mission statement is right there in the title - due to an alleged overlap in membership with the ELF. Without that context, you lose that larger story of the Bureau’s targeting of anti-war groups, and you’re left wondering why the FBI has so many reports on undergrads handing out vegan moussaka.

4. Is this part of a series?

FBI files are roughly chronological, with an emphasis on “rough.” While you tend to see earlier records earlier in the files, things get a bit choppy inside individual sections. The first page of a file might be a memo that was written in response to a letter referencing a magazine article. Those would be included in the file in that order, so you’re left with reconstructing the exact order of events, often seeing the Bureau’s reaction before seeing what exactly they’re reacting to.

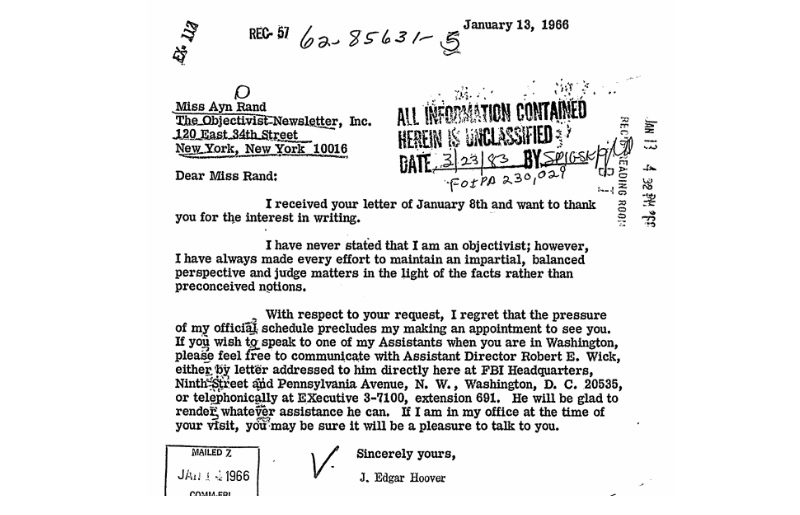

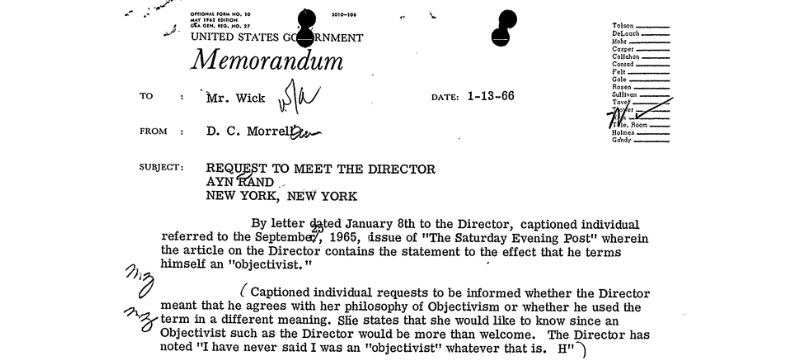

Let’s walk through an example - reading through Ayn Rand’s file, you first see Hoover’s January 13, 1966 letter to the Rand clarifying that he’s not a follower of her Objectivist philosophy …

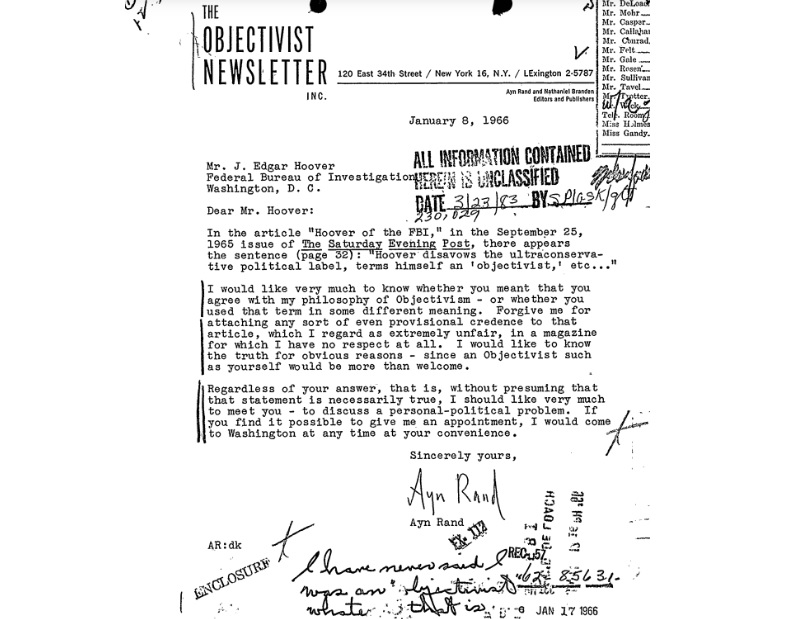

then the January 8, 1966 letter from Rand asking Hoover if he was an Objectivist after reading him describe himself as such in an article …

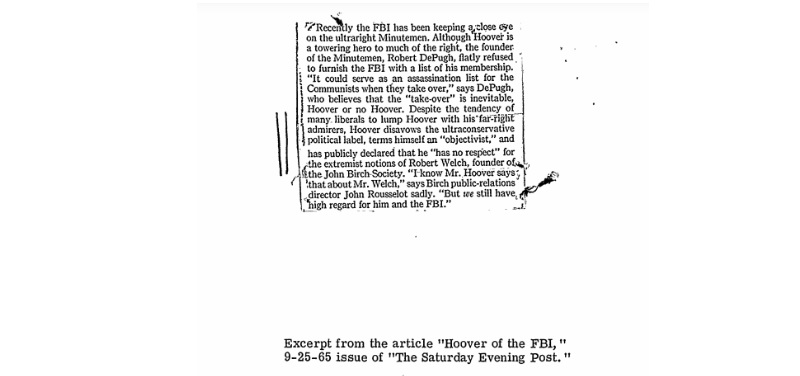

then an excerpt from that September 25, 1965 Saturday Evening Post article in which reported that Hoover refers to himself as an “objectivist” …

and finally, the January 13, 1966 memo responding to Hoover’s hand-written note asking somebody to figure out what “Objectivism” is and recommending the initial letter that kicked off this whole sequence be sent.

So if things suddenly get all in medias res on you, check a few pages before and after and a story should start to emerge.

5. Check the margins!

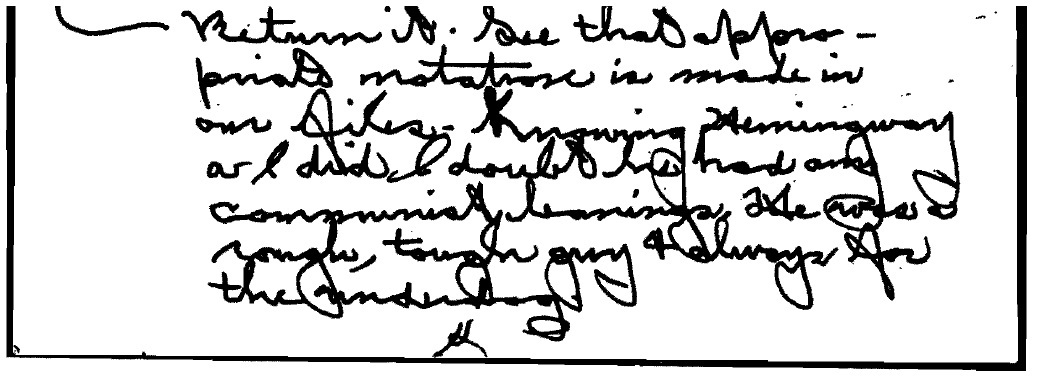

During Hoover’s nearly 50-year reign as FBI Director, it was common practice for typed reports and memos to be submitted to him and other higher-ups and then for their responses to written by hand. Usually, these were scrawled out in the space at the end of page, like Hoover’s eulogy to Ernest Hemingway …

(who, incidentally, Hoover hated when he was alive.)

However, Hoover would sometimes leave notes all over the page, and those would be surprisingly candid - such as when he called Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee a “colossal liar” …

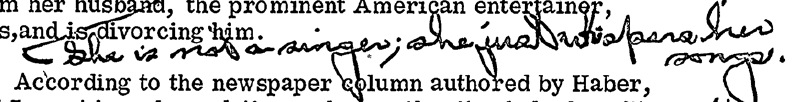

or complained that French bossa nova singer Claudine Longet wasn’t even a real singer, because that happened.

So take the time to translate Hoover’s trademark script - there’s some choice burns in there and a valuable insight into the man himself.

Reminder: Records lie

Okay, now you’re ready to start sifting through records with the best of them. But, first, let’s address that important caveat we mentioned earlier. Repeat after us: Just because something is in an FBI file, doesn’t mean its true. Every single allegation made in these pages should be taken with a grain of salt that you can see from space. Informants lie, agents get basic facts wrong, and on at least one occasion Hoover appears to have concocted a conspiracy out of thin air.

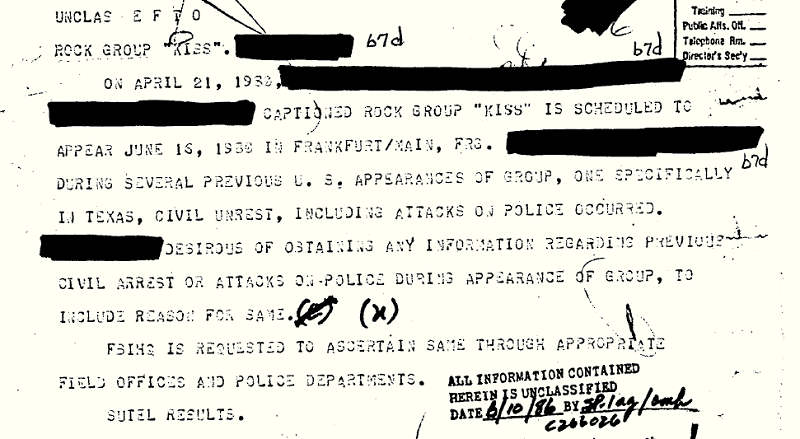

For example, remember that time that KISS riled up a mob in Texas to start randomly attacking police officers?

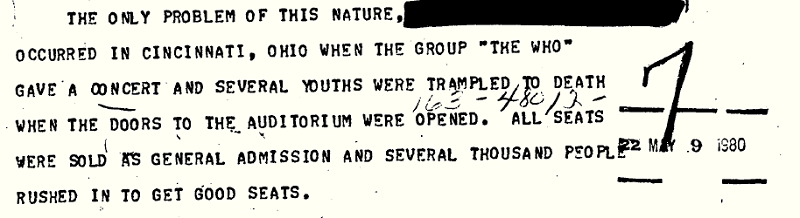

If that doesn’t ring a bell, that’s likely because it never happened - FBI Director William Webster thought it did, but as it turns out, he was probably thinking of that time 11 people died at a Who concert in Ohio.

So whenever you uncover some Bureau bombshell about so-and-so being a secret Communist that danced with Hitler in Marijuana City, just remember that the FBI’s interview with “Mrs. James Baldwin” …

a person who doesn’t exist.

Okay, that’s enough out of us - now jump into the Reagan crowdsource and start siftin’!

Image via FBI.gov