This year, Food & Water Watch joined MuckRock to investigate water privatization efforts in the United States. Together, we filed state-level public records requests to the 100 largest water systems in the country. As a summer intern at Food & Water Watch, I have spent much of my time following up on these requests. Here are some tips that I picked up that could help as you file your own requests - plus some interesting findings!

Why Water Privatization?

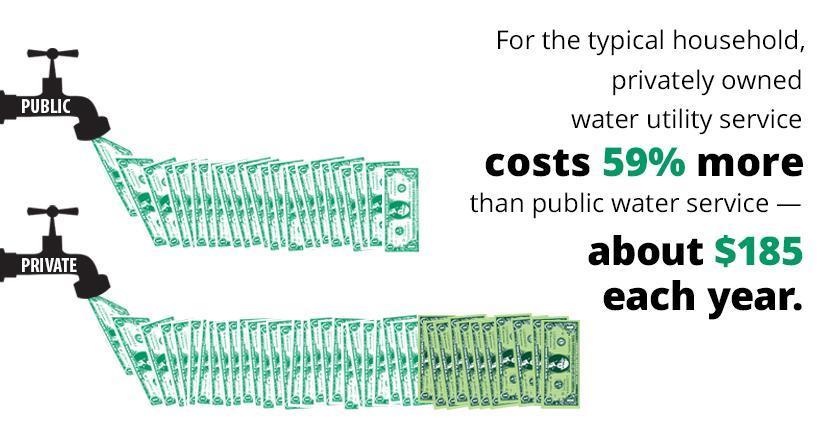

Water privatization occurs when a private corporation takes control of a public water or sewer system by either buying or operating the utility. The industry’s track record has shown that this is a process that harms communities and customers. When private companies are in charge, they are not accountable to the public the way that local governments are, leaving the community with no transparency and little input. Privatization also usually leads to higher water rates than public water service — on average, bills cost 59 percent more — and consumers see more frequent rate increases. Despite their promises, private companies generally have worse customer service despite higher operating costs, and privatization usually leads to job losses. Because of all of these threats to communities’ access to safe and affordable water service, we wanted to assess the status of the country’s largest public water systems to see if they were considering or in the midst of privatization.

Source: Food & Water Watch

What is FOIA?

To conduct this review, we used the state freedom of information laws (FOIAs), which allow the public to request information from state and local governments and related government agencies. Each state has its own law – e.g. the Open Public Records Act in New Jersey, the Sunshine Law in Florida, and the Public Records Act in California. Using these laws, anyone can request access to public documents that have not been proactively released. This can include internal communications, contracts, and even marketing material from private water companies, although what is considered a “public record” is subject to disclosure and can vary by state. These laws provide an invaluable way to see the relationships between public water utilities and private companies.

The Request Process

Most utilities or agencies have a set method for contacting a public records officer to submit a request. Before submitting a request, it is important to look into the specifics of your state’s laws. You should use the correct language and reference the state law (for more information, please see MuckRock’s guide). For example, some states require that you provide proof that you are a citizen of the state in which you are requesting records and will not comply unless you do.

It’s important to note that many agencies will charge a fee for processing these requests, which may be different based on who is requesting. There are commercial requests, media requests, or ‘other’ requests; the relevance of these categories may vary from state to state.

We sought three pieces of information from each city:

-

Existing privatization deals (contracts for the operation, management or ownership of a treatment plant and/or the system)

-

New efforts to privatize (requests for bids and any bids)

-

Communication with water companies regarding efforts to privatize

We kept the requests fairly broad to try to capture various forms of privatization because it can take shape in a number of ways: from just operating a treatment plant to managing a distribution system to outright ownership of the full system. We also aimed to capture the initial conversations with companies that could jumpstart privatization. Large water companies have struggled in recent years to secure new deals (see this report for background), so they have been aggressively pitching cities on privatization arrangements.

Suggestions for Common Issues

Identifying who holds the records

Sometimes it can be difficult to contact the utility or find the correct agency to field your request. You might have to work with the agency to understand who received the request and to get it to the right person, especially because requests for public utilities often have to go through the city or town government rather than directly through the utility. For some of our requests, we heard back only to find out that the agency we had submitted to was not the holder of the records and we had to send our request elsewhere. For others, we had to submit requests to multiple agencies because each was the record holder for a specific type of document we had requested.

Following up on requests

Sending a public records request is no guarantee that you will get a response — and certainly not a quick one. Depending on the state’s law, agencies have a certain amount of time to respond to your request. Unfortunately, they often do not respond, delay their response, ask for clarification about the request, or respond that they do not have any responsive documents.

In order to actually get responses, you have to be proactive with your requests by emailing or calling the agencies to follow up if they have not responded. When using FOIA, it’s important to stay on top of your request. If you do not respond to certain communications from the agency to which you submitted the request, they can cancel the request and require you to resubmit it to reopen it.

Clarifying records

In the process of this project, the most common response we received was “Please clarify which documents you want.” Other common responses included: “What specific timeframe would you like us to search?” and “What type of documents do you want?” We wanted January 1, 2018 to May 1, 2019 for communications and bids, and we specified that we sought “Requests for Proposals,” “Proposals,” as well as any existing “Operations and Maintenance,” “Operations,” “Management,” or “Operations, Maintenance and Management” contracts.

Narrowing the Scope

Since we were asking for internal communications, many utilities had so many relevant emails that it was unfeasible to sort through them and send them all to us. In response, we narrowed down our requests to certain domain names for the largest private water companies in that state. In some cases, we also had to go further and limit our request to only communications between certain people at the utility, such as the head of the utility or director of procurement.

Interesting Preliminary Responses

Although we are still waiting to receive documents from many of the utilities, some interesting responses have already emerged:

Refused or just confused

Some of the utilities we contacted were confused by our request because they were publicly owned. While our request was for communications with, contracts with, or bids from private corporations, many utilities assumed we had mistaken them for already privatized utilities. In reality, we wanted to see if there was any sign of privatization in their future or whether or not there were any known privatization efforts there in the past. To get the utilities on the same page, this sometimes required an email or phone conversation. We explained that we were requesting materials regardless of whether there were known privatization efforts, that we were seeking deals related to the outsourcing of operations of the utility, and that we could narrow scope of the request down to a few specific companies.

Corporate spam to corporate jam

Another interesting trend we are beginning to see is a large number of promotional materials private companies send government utilities, much of which is for conferences or meetings about water system operations. This is fascinating because the companies sometimes include requests for meetings, using the conferences as an excuse to meet, talk shop, and presumably pitch government officials on corporate offerings. Even seemingly benign conversations can be an entryway for private companies to build relationships with public utility officials that might eventually develop into privatization.

For example, information received from a previous information request by Food & Water Watch to Baltimore City revealed that Suez’s Director of Project Development started wooing then-Mayor Catherine Pugh at the 2017 annual conference of the U.S. Conference of Mayors. The company and its representatives followed up with meeting requests and then explicit privatization pitches, as well as efforts to rewrite internal procurement policies. After public backlash to Suez’s efforts and a Food & Water Watch-led campaign working with a broad coalition of local labor and community allies, Baltimore became the first major U.S. city to ban water privatization.

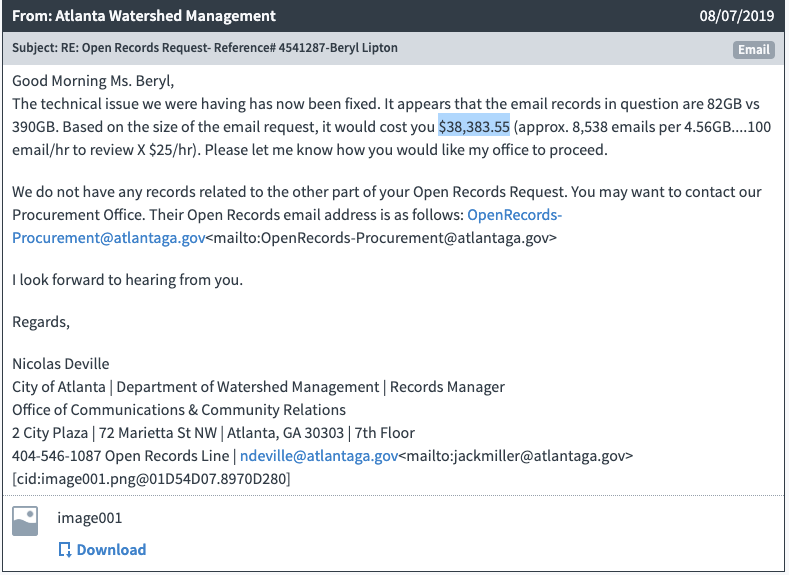

A laughably, prohibitively high fee

Atlanta, Georgia provides an historic example of water privatization gone wrong. In 2000, Atlanta entered into a 20-year contract with United Water, a local arm of a multinational corporation now called Suez. This $428 million contract — the largest private water contract in U.S. history at the time — fell through after only 18 months. United Water had not only cut the water staff in half but had fallen behind on repairs. Their response times were completely inadequate. Amid poor maintenance, inadequate bill collections, and corruption scandals, Atlanta was clearly not receiving the benefits that it was promised by privatizing. In 2003, the contract was terminated (read more here).

As part of our review we submitted an information request to the Atlanta Department of Watershed Management, the government agency that now runs the water utility. However, our request has been met with an extreme fee: more than $38,000! Perhaps Atlanta’s extensive history of privatization means their records are enormous and would cost the city this much to obtain or maybe the high fees are meant to discourage new requests. Atlanta certainly has not made it easy to find out whether private companies have renewed their efforts to control the water system.

This project is ongoing, so stay tuned for more updates and findings. If you want us to file a request to your town, you can fill out the form here, or embedded below.

Image via Food & Water Watch