The AI Now Institute is calling for checks on the datasets used by predictive policing systems because of concerns that the technology can perpetuate, rather than address, “dirty” policing practices.

The group of tech researchers and lawyers based at New York University looked at 13 jurisdictions where the federal government has identified failing or unlawful policing practices in departments that also use predictive policing systems. Predictive policing is a data-driven method of identifying areas where and when a crime might occur and individuals who might commit it. It usually relies on historical police arrest and incident data to help determine where to deploy patrols and resources. AI Now found that there were no barriers to the use of questionable data for training predictive policing systems and warns that the use of such data can actually inject the flaws and behaviors into guidelines for future policing.

“It is a common fallacy that police data is objective and reflects actual criminal behavior, patterns, or other indicators of concern to public safety in a given jurisdiction,” the paper said. “In reality, police data reflects the practices, policies, biases, and political and financial accounting needs of a given department.”

To create the article, the group, led by Director of Policy Research Rashida Richardson, compared the findings of Department of Justice investigations with publicly available information on the police departments’ use of predictive policing systems.

Academics and civil rights advocates who track the use of predictive policing and other efforts to use data to help design plans and procedures, have recently focused their criticism on the “dirty data,” their term for biased data sets, being used to inform algorithms that are then used by law enforcement agencies to make staffing and other decisions about use of resources. In criminal justice and law enforcement, predictive policing and other AI technologies, such as facial recognition and risk assessments to determine sentencing and parole, have been found to create flawed or unfair outcomes, and the datasets being used to inform the algorithmic models are in part to blame.

At least nine of the cities studied by the AI Now Institute had used data from periods when their police departments had been subject to federal consent decrees linked to civil rights violations and other problems in departmental culture and practices.

If these practices included report falsification, data manipulation, or incomplete recordkeeping, any software or algorithm that uses that data to decide future deployments may be inadequate and not based on actual crime or risk rates. The paper also points out that predictive policing systems generally use data from property and violent crimes, with little focus on white collar crimes, despite their frequency and the vast number of people they affect.

“It is extremely concerning that in these jurisdictions where there is established history of discriminatory and unlawful policing practices, that this is almost no public records about data sharing policies or about the predictive policing technology in use or that will be potentially used,” Richardson wrote to MuckRock in an email. “There not only needs to be more transparency about the potential or existing use of this predictive policing, but active community engagement around these decisions regarding the use of limited government resources.”

AI Now released the paper two days after President Donald Trump issued an executive order on Feb. 11 that directed federal agencies to prioritize AI research and review the reasons federal datasets are unavailable or inadequate for AI research. Most AI systems rely upon datasets to train and guide their algorithms’ decision making.

“The four jurisdictions where we were unable to conclude a direct connection or influence were a result of transparency issues. We were either unable to find policies about what data is shared between police departments with dirty data and jurisdictions potentially using that data in their predictive policing technology, or lack of information about the predictive policing technology,” Richardson wrote, noting that even when that material available, the public should maintain a level of skepticism about how “dirty data” could affect the outcomes.

The AI Now paper suggests that the ability of law enforcement agencies to acquire and make use of fair and unbiased datasets is much more complicated than it is treated in practice, and state and local law enforcement agencies are most at risk.

“Both government agencies interested in using predictive policing and vendors of these technologies need to do a better job at auditing the data used to train and implement these technologies but this paper shows that this may not be as easy of a task as previously assumed and in some cases it may not be possible to eliminate all bias and dirty data given the depth and breadth of discriminatory practices and policies,” Richardson wrote.

## Know of an algorithmic development near you? Click here to let us know.

Part of the problem identified by the paper, though, is that even known flaws aren’t always addressed when an AI system for predictive policing is developed. “It becomes clear that any predictive policing system trained on or actively using data from jurisdictions with proven problematic conduct cannot be relied on to produce valid results without extensive independent auditing or other accountability measures,” the report said. “Yet police technology vendors have shown no evidence of providing this accountability and oversight, and other governmental actors rarely have the tools to do so.”

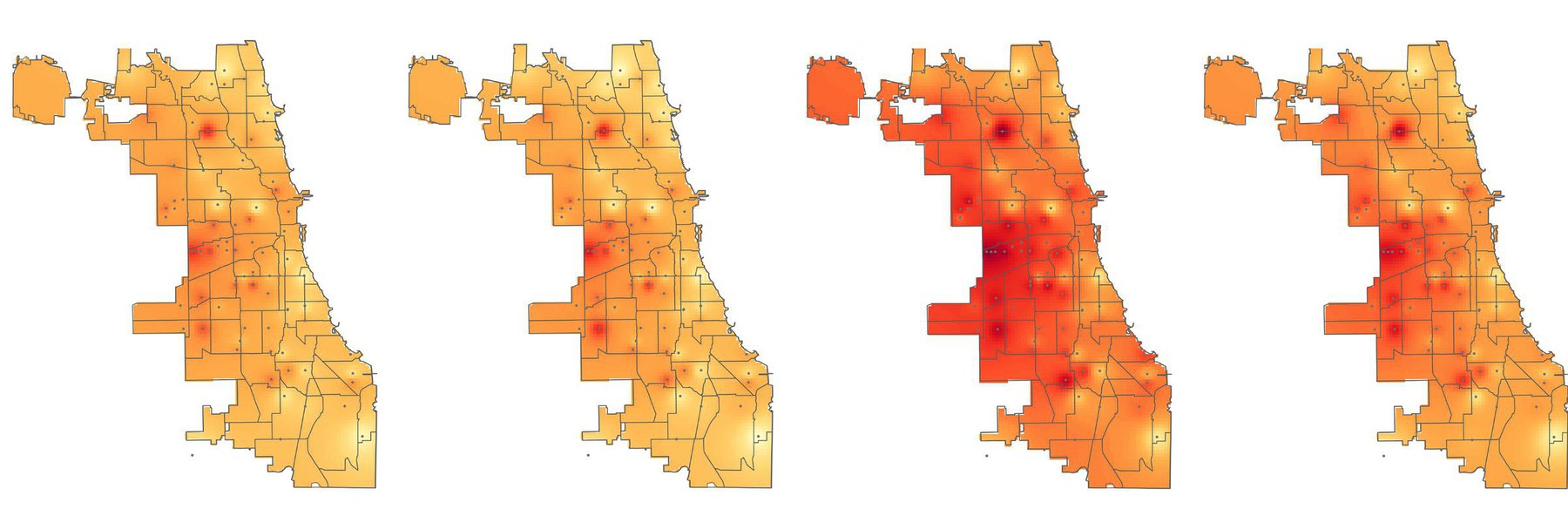

Chicago, for example, has repeatedly been criticized for its racially-biased policing practices, most recently by federal authorities in a January 2017 DOJ report that found the Chicago Police Department from at least 2011 to 2016 exhibited unconstitutional behavior that was then exacerbated by faulty recordkeeping and a lack of accountability. A federal judge approved a consent decree for the Department at the end of last month. During this period, the city also began developing its Strategic Subject List, a collection of approximately 400,000 residents of the city identified as likely to be involved with a crime, either as a victim or a perpetrator. A third of people on the SSL have never been involved with a crime, and analyses of that group found that 70 percent of them were assigned a high risk score nonetheless.

AI Now also highlighted police agencies in New Orleans, Louisiana and Maricopa County, Arizona. Both have been investigated in the last decade by the DOJ and found to have engaged in regular patterns of discriminatory behavior.

Subsequent to the DOJ’s findings, the New Orleans Police Department entered into an agreement with the data mining company Palantir for a predictive policing system, one that was unknown to New Orleans public officials and public defenders for six years until a Verge article in early 2018. The contract was cancelled two weeks after the Verge story. But up until the publication that revealed the system, said AI Now’s paper, the software was likely using data from the NOPD’s unlawful period. The report said there was no way to be certain, but “there is no indication from available government and vendor documents that the NOPD data used to implement the system was scrubbed for errors and irregularities or otherwise amended in light of the dirty data identified in the Department of Justice report.”

The NOPD disputed media characterizations of its work with Palantir and said that further analysis based on public reporting was “inherently flawed.”

“The NOPD did not use Palantir for predictive police work,” said Gary Scheets, senior public information officer at NOPD. “Rather, we used the program as a data visualization tool. The technology was never used to search social media websites to gather information.”

Previously, Ben Horwitz, the department’s director of analytics, had acknowledged the agency used Palantir to create a “risk assessment” database covering about 1 percent of the population. The database, Horwitz said, had been used to target social interventions and to “help hold together criminal conspiracy cases,” according to the Times-Picayune’s Jonathan Bullington and Emily Lane.

Also included in the research were Baltimore, Maryland; Boston, Massachusetts; Ferguson, Missouri; Miami, Florida; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; New York City, New York; Newark, New Jersey; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Seattle, Washington; and Suffolk County, New York.

One of the priorities of the Trump American AI Initiative will be to create technical standards for AI, though what that entails is not yet clear.

“A broad coalition of stakeholders is needed to push public discourse on the drivers and consequences of dirty data, and to motivate government officials to act to ensure that principles of fairness, equity and justice are reflected in government practices,” AI Now recommended.

Read the paper below.

This article has been updated to include a statement from the New Orleans Police Department sent after publication as well as additional context around the use of Palantir technology in New Orleans.

Algorithmic Control by MuckRock Foundation is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://www.muckrock.com/project/algorithmic-control-automated-decisionmaking-in-americas-cities-84/.

Image by Derek Bridges via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY 2.0