The Central Intelligence Agency’s approach to Black History Month could charitably be described as somewhat cynical, often using it as an opportunity to recruit minorities and expand the Agency’s contacts. In other instances, the CIA celebrated the life and work of influential African Americans by displaying photographs of white men honoring them. While the late ‘70s saw improvement over the Agency’s approach in recent years, even in its better moments it continued to lack the critical self-awareness called for when approaching the issues of a minority one isn’t a part of.

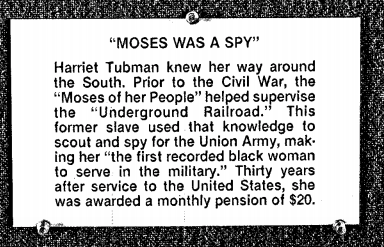

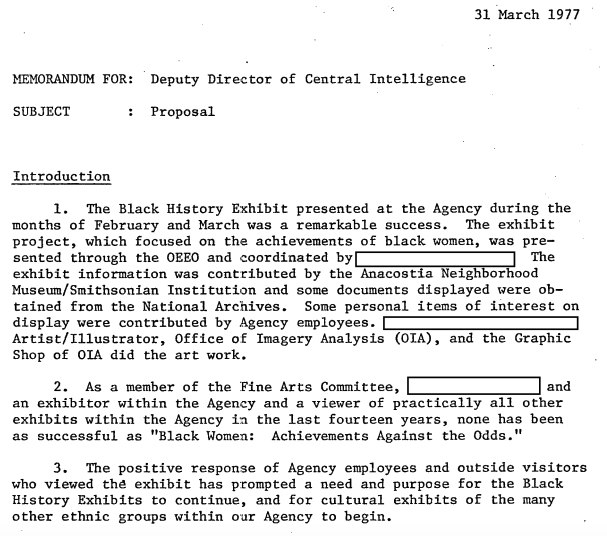

In 1977, the CIA’s Black History Month exhibit was so successful that a member of the Office of Imagery Analysis proposed a permanent exhibit space be set aside to honor different ethnicities. The most recent exhibit had been “Black Women: Achievements Against the Odds,” and it had apparently been more successful than “practically all other exhibits within the Agency in the last fourteen years.” The response from Agency employees and visitors was strong enough to create an argument for such exhibits to not only continue, but be expanded. The unknown author of the memo also noted pointed to a “great change” that had been brought about by Roots as further evidence of the necessity of this kind of exhibit.

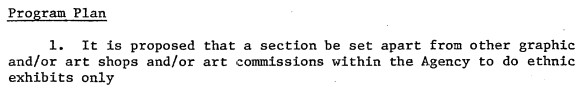

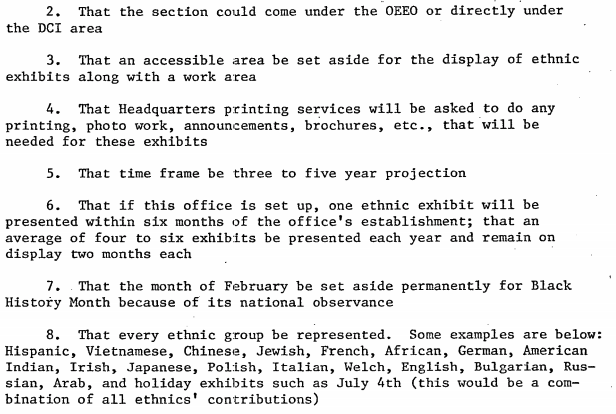

The proposal was for an exhibit space to be set aside for between three and five years, accompanied by brochures and other materials that would be printed by the Agency. Each exhibit would remain in place for two months, giving an average of “four to six exhibits” each year. “Every ethnic group” was to be represented, with some exhibits “such as July 4th” being an amalgamation “of all ethnics’ [sic] contributions.”

According to the memo’s author, this concept would be a step up from the typical agency representation of only “the two major minority groups, Hispanic and Black American[s].” They felt that the then-most recent exhibit about black women had already proven that the program could only be taken as “a positive gesture.” As it’s not immediately clear from the documents in the CIA’s archive whether or not this proposal was approved, MuckRock has filed a new FOIA request to find out.

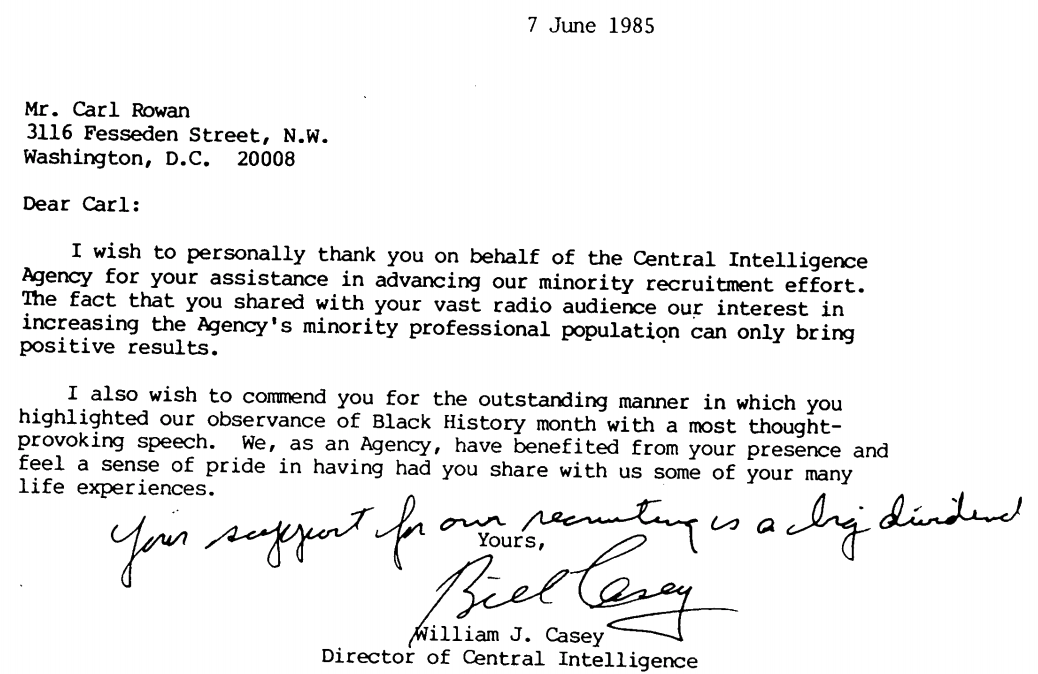

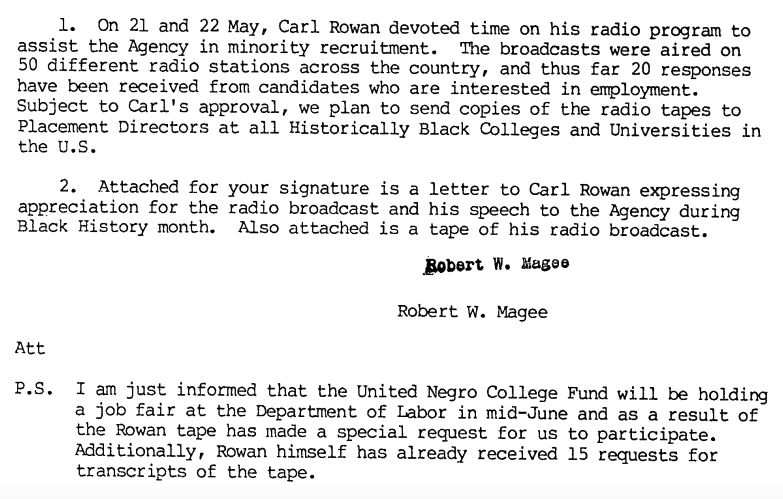

By 1985, the CIA’s use of Black History Month and its associated presentations were actively being turned to the Agency’s benefit. Carl Rowan was the guest speaker that year. That June, CIA Director William “Bill” Casey wrote Rowan a letter thanking him for using his speech at the Agency’s Black History Month observance. Casey noted that Rowan’s presence and shared life experiences left the Agency with a sense of pride. Casey added that Rowan’s support for the CIA’s recruitment was “a big dividend.”

Rowan’s use of his radio program to help the Agency’s minority recruitment aired on 50 radio stations and resulted in at least 20 responses for employment. The Agency was so appreciative of Rowan’s words that they wanted to to send copies of it to all historically black colleges and universities.

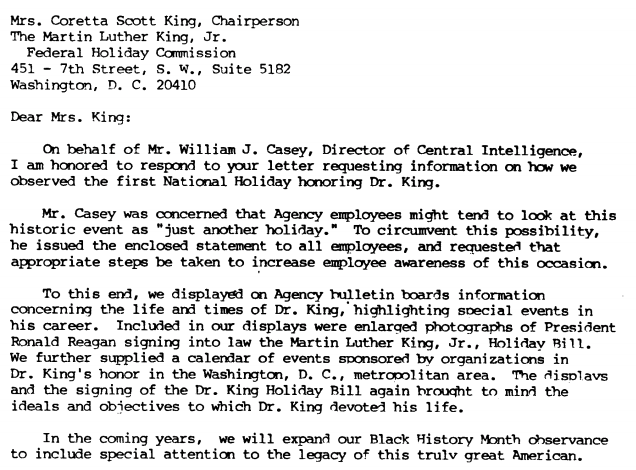

By the next year, the CIA was promising to begin including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in their observances of Black History Month. In a letter to Coretta Scott King, King’s widow, the Office of Equal Employment Opportunity wrote that Casey had been worried people would view the first Martin Luther King Jr. Day as “just another holiday.” To prevent this, the letter explained, the Agency had posted information about King’s life and work on their bulletin boards. The CIA’s whitewashing of King’s work was so thorough that at the centerpiece of the displays were photographs of President Ronald Reagan signing the Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday Bill into law.

Over the following years, the Agency continued to observe Black History Month with guest speakers, such as Colin Powell, who were typically introduced by the CIA Director. These remarks often included historical anecdotes, such as the celebration of the work of James Armistead LaFayette in the American Revolution.

The Agency would continue to use Black History Month as an opportunity for recruitment, going so far as to invite people to the Agency’s Headquarters for additional private conferences and briefings.

While the Agency’s celebration of Black History Month and Martin Luther King Jr. Day may have been cynically bent to fit the CIA’s interests, it was an admitted step up from the attitudes of CIA’s chief recruiters just a few years prior. If you’ve found other documents in CIA’s archives about their celebration of Black History Month, Martin Luther King Jr. Day or the Agency’s recruitment of minorities, let us know!

Image via @CIA