In February 1976, The Village Voice published “the report on the CIA that President Ford doesn’t want you to read,” more formally known as the Pike Committee Report. The report was damning, dealing with covert action and the finances of the intelligence community - so damning, in fact, that it was infamously suppressed. Documents obtained by MuckRock show that the Federal Bureau of Investigation responded to the Voice’s publication of classified information with an espionage investigation. The memos reveal both what triggered the investigation, and what caused the Bureau to expand it to include the Reporter’s Committee for Freedom of the Press.

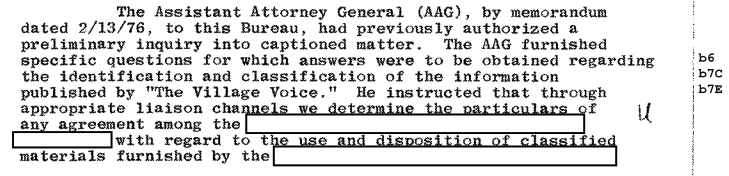

The FBI caption lists the publication as “on or about February 11th, 1976,” while the coverdate of the Voice issue in question is listed as February 16th, 1976. By February 13th, the Assistant Attorney General had authorized a limited investigation. The AAG’s memo listed “specific questions … regarding the identification and classification” of The Village Voice’s publication. The Bureau was also instructed to use their liaisons to investigate “the particulars of any agreement” among unknown parties regarding the classified materials.

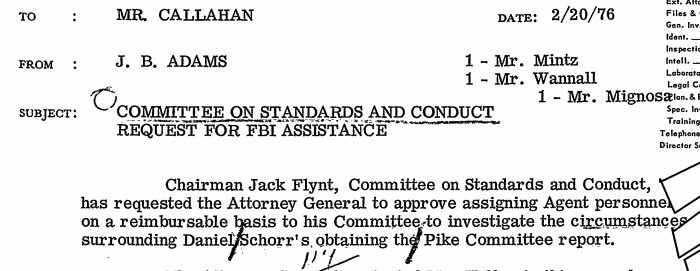

A week later, the FBI became involved in a second investigation of the Voice’s publication of the Pike Committee Report. Congressman John Flynt, the Chairman of the House Committee on Standards and Conduct, requested the Attorney General approve FBI personnel be temporarily assigned to the Committee “to investigate the circumstances surrounding Daniel Schorr’s obtaining the Pike Committee report.” This investigation wasn’t concerned with the publication of the House of Representatives’ report, but rather with its leaking.

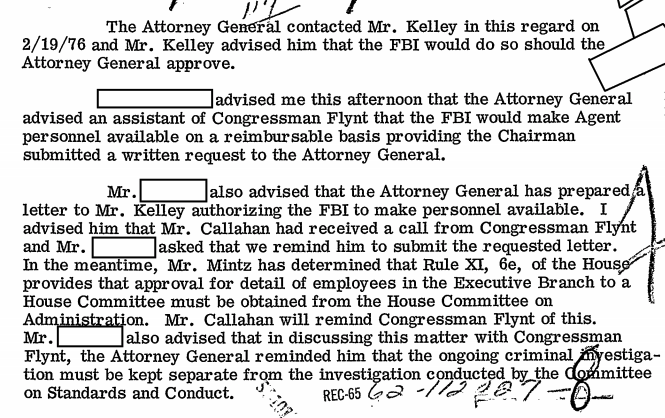

On February 19th, the Bureau expressed its willingness to help the House investigation, pending the AG’s approval. The AG’s office communicated his approval to Flynt’s office and the FBI the next day. However, the House investigation would have to remain separate from the FBI’s criminal investigation. The document doesn’t specify whether the FBI’s investigation focused on the leak or the publication.

In return, James Adams, who was then the Assistant to the Director and would later briefly serve as the Acting Director of the FBI, stated that the FBI would begin its preliminary investigation. The language of the released memo implies that thus far, the investigation was standard procedure, focusing on “information normally secured in leak matters.”

The FBI’s side of the investigation drastically changed on June 9th, when an unidentified woman called the Press Services Office at FBI Headquarters, saying that she worked for the Voice and wanted to provide information about Schorr and the Pike Committee’s publication. Due to the original limitations placed on the investigation, the FBI Agents requested approval from the Acting Deputy Chief of the Internal Security Section. The approval was given, along with instructions to brief the Department of Justice on the results of the interview, which was conducted that same day. From the initial documents provided, it appears that it was this informant’s volunteered informant revived and expanded the investigation.

According to the unidentified informant, her supervisor told her “to get her books in shape” about two weeks before the Voice’s publication because of something that would have the Central Intelligence Agency and FBI “all over them.” Soon after the publication, it became known that Schorr was the source, and that he had asked that profits from the publication of the document be provided to the RCFP. She also learned that a member of the RCFP “had served as a go-between” by connecting Schorr with a New York attorney, who then connected Schorr with the Voice.

According to the FBI’s new informant, the RCFP’s involvement was a source of friction for the group’s members and employees, two of whom she provided details on.

It appears that the financial contribution was a subject of concern to both the FBI and parts of the RCFP. It was specifically included in the Bureau’s summary of their interview, describing it as a donation “in connection with the publication of the” Pike Committee Report.

Several versions of events regarding the donation have been offered. According to Schorr, the RCFP recommended lawyer had found little interest from several publishing houses, but eventually relayed to Schorr an offer from Clay Felker, the Voice’s publisher, that included a “substantial contribution” to aid the work of the reporter’s committee. The Voice initially denied making any payment. Schorr ultimately responded to “misleading impressions” in the press about the payment by identifying himself. The RCFP responded with the following statement:

“The Reporters’ Committee for the Freedom of the Press agreed to accept from Daniel Schorr the proceeds, if any, from the publication, if it occurred, of the Pike committee report on the same terms as any donation - to be used in defense of the First Amendment.

We put Mr. Schorr in touch with an attorney familiar with publishing so that Mr. Schorr could make his own publication arrangements. Mr. Schorr said his plan was to have the report published in book form with an introduction signed by him and the arrangement with the reporters’ committee would be known.

When he changed his plans there was simply no way that, after publication, Mr. Schorr could have expected that a committee of news reporters would not publicly confirm all the arrangements

There was no breach of confidentiality by the reporters’ committee.”

Based on the documents released to MuckRock, it seems what moved the investigation from a standard inquiry regarding a leak to an espionage investigation including journalistic organizations was the financial arrangement. Although Schorr is not said to have profited from the arrangement, The Voice paid money for classified information. Even though the payment went to a non-profit organization, the financial consideration changed the quality and nature of the act. The resulting suspicion of quid pro quo appears to have aroused the FBI’s interest beyond the ordinary, a suspicion that appears to have settled on both the Voice and the RCFP.

MuckRock has filed several new FOIA requests to learn more about the case. In the meantime, you can read the “Espionage X” section of Schorr’s FBI file below.

Image by Beyond My Ken via Wikimedia Commons and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0