Accessing public records can feel lonely - there’s a lot of “no” involved, and everyone from clerks to attorneys general are often united in saying it.

So it’s exciting whenever people band together to push past “no.” When the Richmond Transparency and Accountability Project started in Virginia, they wanted nothing less than open police data. There were protests, “power walks” and other visible ways of matching “no” with a united community voice.

“Being creative about how we approach these problems and relying on the backing of a larger community is really what has enabled us to be successful in this campaign,” the group says.

And, perhaps surprisingly given the culture of secrecy surrounding police records that MuckRock sees every day, their efforts have led to movement. RPD is implementing an open records system - although there are reasonable concerns about those tools and their power. RPD just released proposals here. A recent RTAP meeting offers their insight on records already available, and the proposed system, here.

The group was kind enough to answer questions about their history, and goals, below:

What prompted the formation of RTAP?

This campaign started in 2016 when members of the Southside chapter of New Virginia Majority started by knocking on doors in the Blackwell community of Richmond, asking them about their problems and concerns. They heard from over 700 residents and one of the biggest concerns was the over-policing in the community. The Southside chapter of NVM decided to organize for community oversight of the police department: a Civilian Review Board.

Our coalition started to come together because NVM and Southerners on New Ground realized they shared the same goal of increasing police accountability in Richmond. These organizations held many community meetings, where people had the opportunity to share their experiences of policing in Richmond and showed a lot of support for having a CRB. When we shared this with former Richmond Police Department Chief Alfred Durham and some City Council members, their response was that the stories and experiences of community members weren’t enough to convince them that there was a problem with policing in Richmond, and that we needed data to “prove” it.”

These organizations teamed up with the Legal Aid Justice Center who helped submit formal requests to RPD through the Virginia Freedom of Information Act for information on who they are stopping and why. And Dr. Liz Coston, a faculty member from Virginia Commonwealth University also joined us to help analyze the data that we eventually won. We have been working hard together as the RTAP to fight for public access to policing data because we deserve to know how we are being policed. Our goal is to make sure Richmond can have democratic oversight over RPD and can actually hold officers accountable for their actions.

Could you describe your first request for information to RPD? What response were you expecting, and were you surprised by the answer?

Our initial FOIA request was made in September 2017, and was for data on Use of Force and Complaints against Officers. RPD initially denied all of the items in this request that were not already contained in their annual reports. We resubmitted that request and the community kept putting pressure on RPD to release that information. In February 2018, the RPD began posting that data to their website monthly. RTAP found several deficiencies in that data once we started analyzing it; for example, all use of force reports involving firearms were initially omitted from the data they were posting. Eventually, they corrected this error, after being asked about it during the mayor’s town hall in June.

During the series of meetings that led up to the release of that data, RPD indicated that they also anticipated being able to release data on Traffic Stops and Terry Stops (also known as Stop and Frisk or Pedestrian Stops) on May 1st, 2018. When that data was not released (as we had anticipated), we submitted FOIA requests for that data as well. That FOIA was also denied.

How has the situation progressed from those first denials until now?

After RPD denied us, we kept pressuring them - we organized community town halls, power walks, and eventually meetings with the chief of police and the mayor and petitions to support our cause. In September of 2018, RTAP met with Mayor Levar Stoney and Chief Durham to discuss the denial our FOIA requests. We knew that the RPD gathered much of this data, despite the fact that their FOIA denials stated they did not. Much of the disagreement was about semantics; we requested data on “Terry Stops” and they collect data on “Field Interviews.” Additionally, some of the data we were requesting was being captured in different systems, and they claimed they were unable to produce comprehensive numbers. We responded that we still wanted the data, in the format they were capable of producing it in, even if that meant we couldn’t access some of the items we initially requested. For example, we wanted to know if searches or seizures of property occurred in relation to pedestrian stops, but the Field Interview Reports didn’t capture that.

As a result of the meeting, RPD agreed to produce a timeline for releasing those final pieces data on Traffic Stops and Pedestrian Encounters. On October 22nd in addition to producing that timeline, the RPD attached a $4,500 price tag to that data. As we represent the interests of some of the most economically vulnerable groups in the city, we were appalled that the police would attach such a high price tag for our residents to learn about how their communities were being policed. So we started a petition asking the mayor to waive these fees and release the data. With the help of the community, and as a result of our petition, we eventually received most of the data that we had asked for (with the exception of searches and seizures) at no cost.

What are the next steps for RTAP?

RTAP will continue fighting to ensure that all of our communities are being policed fairly and equitably. Much of that work recently has been making the findings from the data on policing in Richmond are available to community members. For example, we recently held a town hall to share our findings with the local community and had over 50 people in attendance. Mayor Stoney has also committed to a public input process for the implementation of the new Records Management System that RPD is in the process of implementing, so advocating for putting systems in place that will protect and benefit Richmond residents will be one of our main priorities. We discussed the new system at the town hall as well, and heard resoundingly that our community doesn’t want RPD to use this technology for predictive policing. We have invited the mayor and chief of police to an event to discuss these concerns in more detail and are anticipating a response about this soon.

Can you offer any advice or tips to people who might be seeking police records in other areas?

Our biggest piece of advice would be not to give up. We hit a number of roadblocks in trying to secure this data for our community, but whenever we came up against one of those roadblocks, we looked for another way. When city council said that they needed data, we went to the RPD to get their data. When the RPD told us they couldn’t produce the data, we went to the ,ayor. When they attached a massive price tag to the data, we relied on the power of the people to sway our officials to do be accountable to their constituents. Being creative about how we approach these problems and relying on the backing of a larger community is really what has enabled us to be successful in this campaign.

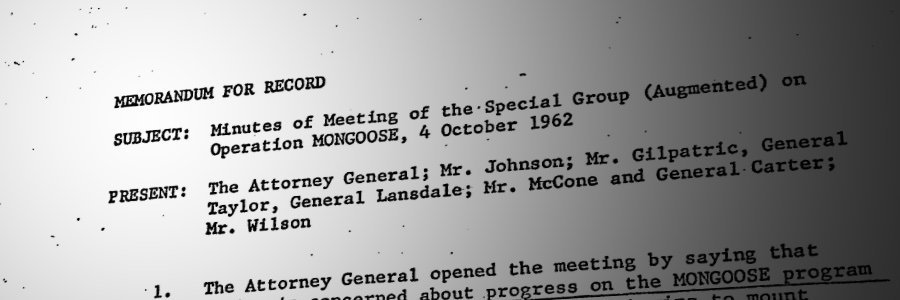

Image via RTAP Facebook