It’s likely most Americans have never heard of Clearview AI, Inc., but many still have a good chance of being in the company’s massive facial recognition database.

Technological capacity for collecting, storing, and analyzing images is growing, and Clearview is one of the private vendors accelerating the trend. The company claims to use “billions of publicly available photos, including news articles, social media accounts, and public mugshot databases,” which is used to find matches when an image needs to be identified.

Typically, such facial recognition identification is based on numbers. The system analyzes a face for particular measurements and ratios, and then based on that model, the image is compared to a database of known or existing faces. The ACLU and academics have pointed out facial recognition is trained on and created by those with Caucasian-featured faces, reinforcing race-based biases in policing.

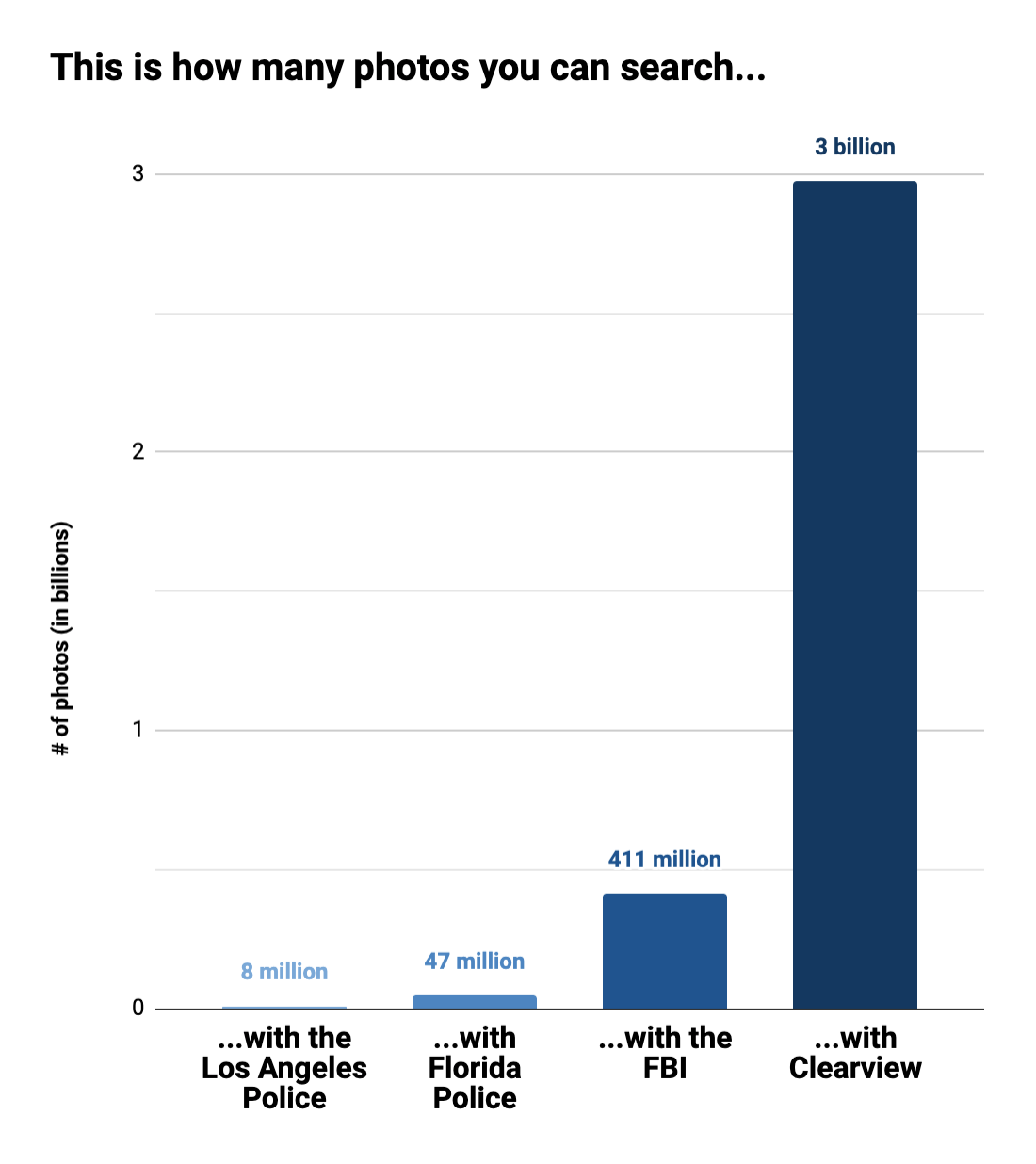

Facial recognition databases can rely on mugshots or drivers licenses for faces or can be open-sourced from the streets and cyber highways of the United States. But Clearview AI uses open source images, and their self-reported 3 billion-plus image inventory is many times larger than comparable collections and the largest set we’ve seen available.

Facial recognition technology is the frontline of the fight between tools meant to promote public safety and Constitutional protections. Companies developing facial recognition tech are evolving more quickly than lawmakers can address basic issues or create consumer guards. Can your online photo end up in a commercial database indefinitely? Could the Department of Motor Vehicles sell your driver’s license photo? Do police departments use this tech to find out where individuals have been and when? For now, the de-facto answer to questions like these is yes.

In collaboration with Open The Government, MuckRock requested materials from the largest police departments in the country, including Atlanta, Georgia, which first released records on Clearview AI.

As part of that project, Police Surveillance: Facial Recognition Use in Your Backyard, OTG’s Freddy Martinez then requested information about Clearview’s business in other locations, including Gainesville, Florida and Clifton, New Jersey.

In one August 2019 record from Atlanta, an estimated 200 agencies were reported to use the Clearview system, and police officers are sharing their access with other agencies, according to documents received through a MuckRock request.

Our requests asked for a few basic elements to help us learn more about where and how police departments are acquiring and using facial recognition. We asked for contracts and agreements, communications about the technology, guiding policies, and invoices.

The releases from Atlanta and Gainesville to MuckRock include emails, contracts, and legal briefings.

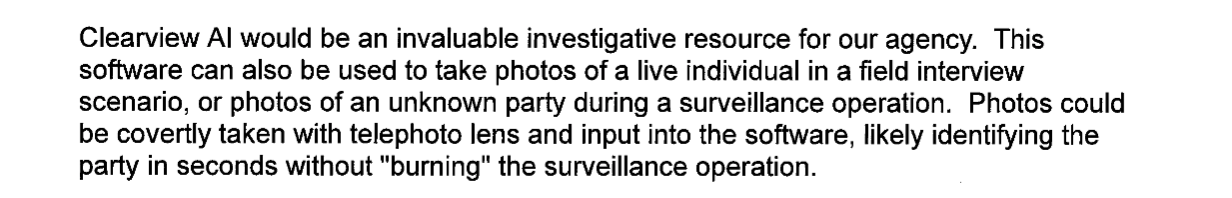

In a release from the Clifton Police Department in New Jersey, emails show officers were attracted to the Clearview system in part for its ability to run searches on individuals in the field without informing them.

The releases also highlight multiple instances of police voluntarily using their access to the system to assist in identifying suspects for departments in other jurisdictions.

Early Saturday, The New York Times released a report on Clearview and the materials found in our requests. Clearview told the New York Times that, using the billions of photos it has scraped from millions of websites, it can find a match for an individual’s face up to 75% of the time. The company also reported that its customer base has actual grown to more than 600 law enforcement agencies and some private security companies. It also has created code to link its facial recognition app to augmented reality glasses, advancing the ability to apply facial recognition analysis to any face one sees on the street.

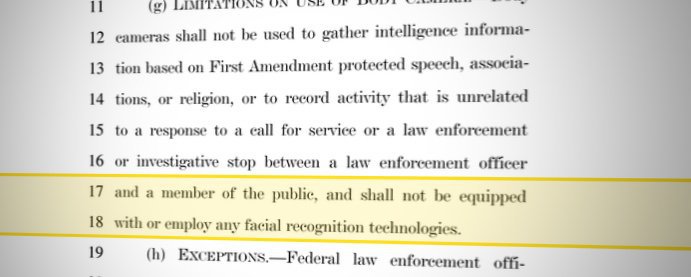

Some states and cities have moved to address concerns about facial recognition by banning the technology for policing and government use: San Francisco and Oakland in California, Somerville, Cambridge, Brookline, and Northampton in Massachusetts. Oregon and New Hampshire have banned the use of facial recognition in body cameras for police officers, limiting the way police can collect and use footage of those who happen to be within sight as they work; California recently passed a similar law, though the moratorium will only last three years.

“[W]ould you support a new law that said whenever you go into public in Somerville, you need to wear a digital barcode around your neck?” asked Ben Ewen-Campen, the Somerville City Councillor that proposed the successful ban. “I don’t think people realize that that’s what facial recognition technology could become.”

Bring it home

In most cases, the adoption of new technology, even facial recognition technology, is something government agencies do without much notice to the public.

That is, of course, unless they’re asked.

That’s why we’re helping people to file their own requests on the facial recognition technology being used in local communities across the country.

You can explore the chart below to see if we’ve already asked your town or city about their use of facial recognition.

You can find a guide on how to file your own public records request here.

You can also leave it to us. Simply let us know the jurisdiction or police department you’d like for us to check.