Kris Newby is a science writer, a MuckRock user, and the author of Bitten: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons, which was deemed the winner in the Narrative Nonfiction category at the 2020 International Book Awards.

Newby recently shared her personal journey that took her from the beaches of Martha’s Vineyard into the depths of the U.S. government’s Cold War biological weapons program, what she found there, the FOIAs she filed along the way, and what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had to say about her.

Requester’s Voice is a MuckRock series in which we interview public records requesters about the experience of using the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). You can find the whole series here. Interviews are edited for length and clarity.

How did you get into this investigation? What was your life and relationship to government records like before you started digging into the government’s weaponization of ticks, and what ignited your interest?

So I started out as a tech writer in Silicon Valley on the industry side, so I only wrote happy stories with happy interviews. I had run my business for about 10 years, and then my husband and I went to Martha’s Vineyard with our family for a week-long vacation.

When we came back, my husband and I were just sicker than we’d ever been, and that started our journey with the dysfunctional medical system. It took us a year, 10 doctors and $60,000 dollars to get diagnosed with Lyme disease and Babeseois, both of which are endemic on the island in the state that is the number one state for Lyme disease.

I’m an engineer, so I kept meticulous notes and spreadsheets of the symptomatology. We both got sick on the same day. We came back to California, and every doctor we saw, I said, “It might be Lyme because it’s a Massachusetts problem and there are signs warning of ticks all over the island.” And the doctors would say, “Oh, no. That’s a really rare disease.”

And we got sicker and sicker. About eight months into it, I could no longer work. I could barely get out of bed. I had horrible symptoms. You know, combine early Alzheimer’s, M.S., irritable bowel syndrome, and brain fog. I would get to a traffic light while taking my kids to school and not be able to tell what the red, green and yellow meant on the traffic light. My cognitive processing was so slow.

Finally, our doctors at Stanford tested for Lyme disease. They tested for 20 things, and Lyme came up positive. So I was like, “Yay!” But then I came in for my treatment course and was told, “Well, you’re fired as patients. We don’t have the tools to treat you here.”

There was an unwritten rule that they don’t treat chronic Lyme patients, and since we had not been treated for a year, we had chronic Lyme. It’s like the system’s designed to create chronic patients and then they don’t acknowledge that chronic Lyme exists.

That was the driving force for me. I said, “Well, it’s just a lack of education, and if I do a film, then I’ll fix it.” I spent the next three and half years while I was recovering working on the film, Under Our Skin.

That was my first step. I started this documentary with Andy Wilson, a really talented filmmaker in Marin. That’s when I became a journalist, really, while I was trying to figure out why there is such a big disparity between what’s in the field and what academic medicine says. It was do-it-yourself journalism.

The film was released in 2008 at Tribeca — 350 hours of interviews with patients and experts and then you have to crunch it down into an hour and a half. It was just really eye-opening to see how many people were suffering and the complete denial of the CDC to what was going on.

Then there’s a very small handful of academic researchers who had a monopoly on all the grants. There’s 12 guys and they’re not in the same university. They don’t have an org chart, but there is an invisible org chart there. You can see the connections, if you start looking at who publishes with whom and then I realized how the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant system could be rigged, because there are these, like, 30-person grant review groups. And usually of these 30 grant review groups, two people do the detailed reviews of the grants. They can’t be at the same university as the person filing for the grant. But if you have this invisible organization, you can put your sentries on that and they can blackball your competition and only give you the grants. And same with journal reviews. I did a huge spreadsheet of the 60 high impact medical journals that would publish things about Lyme disease. And this cartel actually had sentries on those article review committees, on all of them, except for two, which is Science and Nature, who have staff reviewers. So it was an invisible cabal.

That’s where my CDC FOIA came in. I had [the names of] the guys in academic medicine that were interacting with the people in CDC, and that’s completely illegal, you know, to show favoritism in the awarding of grants. But here was this group that had group bias and it was to the detriment of good science.

Do you feel that is intentional? Maybe these are sort of normal or natural sort of societal biases or connections? Have you encountered people who say: this sounds like a conspiracy theory?

Because I was at Stanford for 10 years, I’ve talked very candidly with professors who are NIH grant recipients, and I mean, to them this is just rampant anyways. What was magnified with Lyme disease: it was a new disease and there wasn’t much funding. That bias was magnified, I think, by that small group of people and the small amount of money and the fierceness with which they fought for those dollars. I mean, at that time it was like 10 million a year, which is nothing [for medical research].

So you worked on the documentary and - and what? Where did that take you?

Well, it’s three and a half years of the researching and then it’s a year and a half of marketing it, because what happens is, first of all, you go on the indie film festival circuit and you get following and and you get people’s attention and then you apply to the Oscars and to apply to the Oscars you have to have it shown for a certain number of times in L.A. and New York. So I was traveling around and doing that.

And then I learned so much about medicine. I ended up getting a job as a communicator at Stanford Medical School, which is fabulous. I learned so much there and became a real science writer-reporter. I had some great editors there. Like my mentor editor was a former New York Times reporter, and then he became the bureau chief in Connecticut. So he really taught me how to write a great lede and and, you know, taught me the importance of fact-checking and all that, so that was fantastic.

And then I was done with Lyme because it was very emotional and a hard journey, and I was paid practically nothing to do the film.

Plus, you were still struggling with actually having Lyme disease while you were trying to make the film.

I was. I would take oral medicine and I’d be fine for a month or two months, and then the symptoms would come back. And I knew I needed I.V. antibiotics so they could bypass my very healthy liver and get to my head, but at that time — well, it was after 9/11, and you couldn’t travel through airports with bags of fluid for the pump. So as soon as I got done with the film, I went on an I.V. and then once I was feeling good for a year, that’s when I applied for the Stanford job.

So, anyways, I was done with it. It was a hard journey. And I was learning stuff at Stanford that was really interesting, and my faith in medicine had been restored because there were so many positive people, not negative, like the ones I dealt with with the Lyme disease.

And then — then these two things happened that made me feel like I couldn’t walk away from the story.

One was that I was at a party and someone told me that — he’s a confidential source, so I can’t give you any details but he was absolutely a real guy — he was talking about his time in CIA dark ops during the Cold War and he told me some horrendous things he had done. And then he said, “The strangest thing I ever did was drop two boxes full of ticks on Cuban sugar cane workers during the Castro regime as part of the total economic warfare and revenge for Bay of Pigs.”

So, I kept, you know, encouraging him to talk. He had no idea my relationships to ticks, right? And I would run into the bathroom and I only had one piece of paper in my little purse, and it was a Barnes and Noble receipt, and I just took down everything he said.

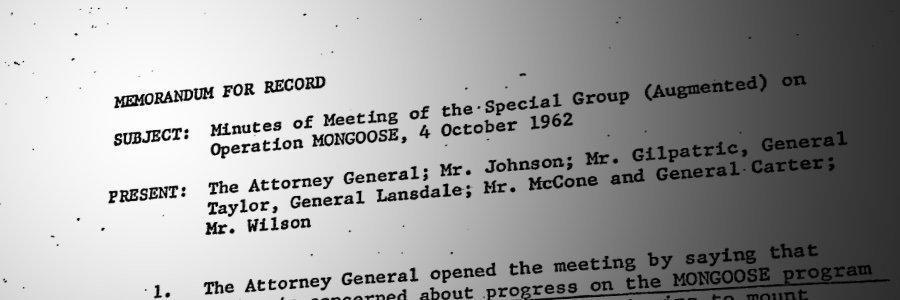

That’s when I didn’t know anything about the Cold War and he gave me the names of operations like Operation Mongoose and his commanders in the field. And I just kept those notes for about six to eight months.

Then another thing happened. Another indie filmmaker went to talk to the discoverer of Lyme disease, Willy Burgdorfer, and he told him in this interview that he thought the outbreak of tick-borne diseases in Lyme, Connecticut was due to a biological weapons experiment gone wrong. He wouldn’t give any details, but you could tell from the video interview that — I thought he was telling the truth.

It’s like, oh, you know, this is sort of a dangerous story. It could take at least a year to understand the politics of the disease, and I knew all the players from the film. I knew the black hats and the white hats. So I just started doing that investigation on the side. And that took five years.

The thing that was interesting about it was I had the confession and you realize one person’s point of view you can’t just take that as gospel truth. You have to back it up with documents.

I knew that NIH had come to Willy’s house and taken away his scientific papers to archive them for historical purposes. I had requested them during the film, but it took — somehow it took four years to get them into the National Archives. And, finally, while I was thinking about writing this book, they became public.

So I went out to D.C. and I looked through these 33 boxes of supposedly all his research in his life, and the one thing there is nothing there about was his Lyme disease research. There were no documents, lab notebooks, slides of the Lyme stuff, which is just really weird, you know? The thing he’s most famous for is not in there.

So then I went out to see him. That’s when he said, “Yeah, I was in the biological weapons program during the whole Cold War. I was a consultant to Detrick. They asked me to put plague in fleas. They asked me to try and figure out how to make, how to reproduce ticks really quickly so that you can drop boxes of them on people. I tried to package fleas with plague so that you could drop them in bombs that would burst open above a battalion-size area.”

Then I went into a research hole to try to learn microbiology and figure out what was going on in his files and his letters and learn the people and I sort of hit a dead end. And then I had a lucky break because after my going out there to interview him, he had a crisis of conscience. He called up this professor at BYU, which has a very nice historical archive and says, “Professor, there’s some files I didn’t give the NIH. Would you come up and get them and put them in the BYU archive?”

This professor’s whole family had been impacted by Lyme. He knew about my book project, though I had never met him. He called me and says, “Hey, I just loaded my SUV with all these files that no one’s seen on Willy’s biological weapons work. Do you want to look them before I archive it?”

I went to his house and had boxes on his pool table with a big piece of plywood, and my husband and I just went through them and took pictures of the important ones. That’s really where I found out he was an important cog in the wheel in putting various diseases in ticks, some of the most dangerous diseases in ticks, mix and matching them, because they wanted ticks that you could drop on the Soviet Union. There was a box of documents, ancient Detrick stuff from the early 50s, which is the most damning stuff.

Whenever [Burgdorfer] was writing something important, like a scientific paper, if there was a paragraph that was key, he would switch from a black pen to a red pen. And there was a yellow sticky on the top of this box that said — it was in the red pen — it was his distinctive writing, and it said, “I wondered why somebody didn’t do something. Then I realized I was somebody.” It was like a confession.

Just so we’re clear: there is no question that the United States had a biological weapons program and that it was spreading and weaponizing diseases?

The biological weapons program was competing with the Manhattan Project and the nukes for funding. It was considered a poor man’s nuke program. Some economists from the army had actually calculated that, “Oh, you know, it only costs $1.60 to kill people with tularemia by spraying it over a city. Only $1.60 a person. It’s much cheaper than nukes. And plus, you’re not going to destroy the buildings.”

People would write these things. So there is, yeah, no question. I got a lot of pushback when the book came out from the military folks when Chris Smith in New Jersey added an investigation into weaponized ticks in the DOD budget last year. It got killed and now he added it this year.

There is no question that we weaponized insects for war. Through most of the 50s and in the early 60s, we had a series of feasibility studies of packing ticks, fleas, and mosquitoes with dangerous pathogens — some incapacitating, some deadly — to find the perfect mix for the Pentagon’s objective for a certain area. There is stuff they wanted in Vietnam, stuff they wanted in Siberia, Kiev, you know, to attack the breadbasket of the Soviet Union with anti-crop and anti-personnel and incapacitating weapons. No doubt of that.

The thing that was new that the book brought out was the extent of the tick-borne weapons program. And also that we actually dropped infected ticks on Cuba and that we released hundreds of thousands of Lone Star ticks and other ticks in coastal Virginia, made them radioactive so that we could track them over months and years to see how far they would spread if we were to drop them on the Soviet Union.

The problem is there were uninfected ticks that we dropped in Virginia, but back then, we didn’t have the tools to know that those uninfected radioactive ticks had viruses in them or were contaminated in Willie’s lab, you know, which had happened before.

I’ve seen oopsy accidents. You know, they were doing an experiment in Canada to see if you nuke a town and then release infected ticks, are the resulting diseases worse? So he sent clean ticks, but some had deadly relapsing fevers. So he said destroy them. So accidents happen all the time. And there’s no doubt we dropped them.

Foreign soil where we definitely dropped infected ticks was Cuba. That I verified from multiple sources, including JFK files on Operation Mongoose and an eyewitness testimony. There are rumors that we dropped insects on Korea and Vietnam. I have a vet who said he saw infected lice thrown in little paper packets down foxholes in Vietnam, but he won’t go on the record. And other people are working on Korea and Vietnam to prove that we used weapons on them.

The point I wanted to make in the book is there were hundreds of open-air tests with live bacteria. In a couple places, there were the actual pathogens. Mostly they were simulants, but still people got sick because of that.

So what I want is the government to come clean with these 50-year-old documents that say this is what we dropped where and here are the preventive measures that we developed for our own soldiers. The pattern for a tick-borne disease is just so weird. The first cases of Lyme happened in Wisconsin and were shortly followed by Lyme, Connecticut and the Long Island area. How does an outbreak simultaneously occur in Wisconsin and in Lyme, Connecticut? Unless the vector is a military plane? We need to know that. It’ll save a lot of research dollars and lives.

Some of these data points as you were happening upon them must have been just mind-blowing. Do you remember that experience and how you moved through that?

I think there were places that were really dark, especially if you’re reading about the Pentagon’s plans for creating chronically-incapacitating diseases and I’m living through it at the time.

They would have, say, a bacteria, and they would feed it in a slurry of toxins and viruses. So then they’d have this — I call it a Russian doll sort of bioweapon because within a germ, there is another germ and a toxin. The Soviets did this and we did it. You would mass produce this Frankengerm by the tons, freeze dry it, make it powder, find out the perfect particle size and feeding medium, so that you could spray it over a city. And they had done the calculations of how much they needed to cover a city. And then the people would get sick with this really ill-designed, ill-defined disease. It was hard to diagnose, crazy symptoms, but they would just give patients antibiotics, and the antibiotics would kill the bacteria, but release the virus and the toxin, and the person would die.

You see their plans for incapacitating agents, and you say, wow, this just sounds exactly like what I lived for, for five years.

So you have this heaviness.

And at the time I’m working for Stanford and my group is NIH-funded, and I’m looking into one of their hero scientists who worked for the NIH and worked on biological weapons. There’s this sort of thing where I can’t tell anybody at work what I’m working on outside of work, on vacations and weekends and nights. And then I have friends that I know really well and they’d say, “Oh, you’re working on a book. What are you working on?”

“You know, insects of mass destruction.”

Look at me at the cocktail party. No one wants to hear about that stuff. I was telling my mother-in-law, you know, “Hey, I found this really interesting thing.” And she goes, “Stop. I don’t want to think that my government does that kind of thing.”

Yeah, this is very, very dark stuff. Some of these things you were able to substantiate with records. Are you concerned at this point, though, that some of these things are going to be lost in the destruction of records? I know that some of the materials you’d come across, you were told they’d been gotten rid of as part of the regular retention schedule.

I think a big burn off happened in between 68 and 70 at Detrick. There was a public show. But I mean, I had at least one witness say his generals said, “Get rid of these Japanese interviews,” and he put them in the trunk of his car. People felt like that was wrong on some level, that we might want to know. So there are these pockets of documents. Willy did the same. This other Detrick person did the same.

So then I would file FOIAs, and I would think 360 degrees. What are the other ways I can get these documents? Everything in the government is filed in triplicate. There’s the planning committee, the minutes, and I got a lot of really interesting stuff from the University of Wisconsin, because Ira Baldwin was sort of the visionary for the whole biological weapons program and he’s the one who sort of visualized the military-industrial complex; he sort of started that out of Wisconsin, and he was a meticulous documenter, so I just went to Wisconsin to all his files. That was like the table of contents for the names of the documents that I could FOIA later on. So I was thinking about where all these documents would be.

Could you talk a little bit more about that relationship between shoe-leather reporting and filing some of these FOIAs and the FOIAs you’d filed across many different agencies.

My philosophy that has developed over 10 years of these investigations are: think about the information that you need, and the first thing you do is to file a FOIA. Peg that date down and realize it’s going to take at least a year to get that answer. And then once you do that, then think of every other place there could be a carbon copy of that somewhere in the system. And then also look at everything that’s been written addressing that question in book form and go to the endnotes and see where those people got their information, and then search the FOIA logs and see if anybody else requested that before.

Then, I’d just go to LinkedIn and say, “Hey, Mr. Journalist, can I have a copy of that?” And almost always, you know, your journalist brethren will share. And now I have people looking at my own notes saying, “Can you send me that document?” You know, like, Pulitzer Prize winners. “Sure. Here’s the baton. You take it now.” We’re all on the same side.

I think this is a trend in citizen journalism. I would say if you look at I’ll Be Gone in the Dark by Michelle McNamara, who did all that investigative crowdsourcing work through her podcast on the East Bay Rapist. You know when I was looking at how to structure my book, I looked at her book and said, this is sort of interesting, where she talked about her process of investigating this. And I thought, “Well, that could be inspirational to other people trying to do this.”

I came to journalism late in the game. I didn’t go to Columbia Journalism School. I can never be part of that tribe. Still, Willy discovered Lyme disease, but no one’s explored what happened in the lead-up. It’s not like the disease didn’t exist until Willy saw it. So I went through newspapers to see where these mysterious animal die-offs happened. I went through the case studies from clinicians at Mass General in Boston to see what are the earliest signs that they saw this epidemic emerging and spreading further and faster? To me, that sleuthing was just so interesting, but no one would pay me for it today. In the 24-hour news cycle, no one would pay me to spend five years working on this. It took me a long time to do the book, and I wish I had more focused time, but it’s the compromise I made. I needed to pay my mortgage and so I did this staff job with Stanford and did [the book] on the side so I could do it my way.

That’s awesome you were able to interview Wily before he passed away.

I actually interviewed him about four or five times, a couple times on the phone and two times in person. That was lucky.

So that’s my other bit of advice when you’re researching the Cold War: if there’s someone who’s over 60, don’t delay on the interviews because you never get the information you need in the first interview. It takes time to develop that relationship, and a lot of my witnesses died before I could get all the answers. Even young ones. Work hard to develop the trust and the relationships and don’t kick that can down the road, because once that person dies, that information is lost forever. One thing I feel good about the book is if I hadn’t pushed Willy, all that information would have died with him.

One thing I learned from the Investigative Reporters and Editors conference (IRE) is once you publish a journalistic work, an article or a book, immediately file a FOIA for that publication and your name. I did that at the NIH and the CDC. I recently got back the NIH one, which is super interesting because when they heard the rumors of my book coming out in January, they said the worst things about me. “Oh, she has no credibility.” “She’s a yellow journalist.” “Wow. She’s from Stanford. Well, even Stanford has a shit once in a while.” They said horrible, horrible things about me in January 2019, when the book was not even done. It was in the publishing process.

Then the book came out in May, and they read it. And it went up to the highest levels of the NIH legal department, and they were discussing suing me. I wouldn’t have slept for a month. But then they went radio silent because I think they realized that it was credible and backed up and they didn’t want to give the story oxygen. So nothing happened.

I’d given it a quick read and I felt really horrible when I read the January stuff, the horrible things they said about me. So it took me, like, two weeks to get enough courage to read through it, and then I realized when I put it in order that, oh, OK, so their opinions were based on not reading it. And then once they read it, there was respect.

Then what I found is that the people who dissed me in January, about six months later, they published a scientific study. They were colleagues of Willy that were trying to answer some of my questions that I raised in the book: hey, did we hyperfocus on the Lyme disease bacterium and not look at the other co-infections in the ticks that might have been causing that disease? So they did a literature review of all co-infections. In a way, that’s what I wanted for the book. I wanted them to take it seriously enough to push the science and not sweep all this under the rug like had been done.

With the CDC, I did the same, but CDC, serially, is the worst. They thought of every way to reject a search on my own name, so I had to create a notarized document, pay to have it notarized, and to say, “I am who I am and I want you to release everything said about me in the CDC in the last six months.” So then they rejected it because it wasn’t the wet-ink signature that I put through snail mail; I’d sent a scan of it. Now it’s back in the system, and I don’t know when I’ll see it ever.

What is the importance of getting them to acknowledge that they were involved in this for people today who are really dealing with this disease? What is the value today of this information?

The epidemic continues to spread. Since tracking started in the early 80s, the cases of Lyme disease and associated tick-borne diseases have continued to rise. It’s getting to be a huge problem. It breaks up families. People lose their jobs, lose their houses. Their marriages break up. High school students have to drop out of high school and be cared for by their parents. It’s devastating socially and economically for our country. And it’s an unacknowledged epidemic. The small cabal that’s been sort of controlling the academic information has blamed it on [other things]. Oh, it’s global warming. It’s people building houses closer to deer. But what this books says is, “No.” This increase in ticks and tick-borne diseases could have happened naturally, but the fact is that three brand new diseases never seen in man showed up in this small area in the late 60s. It’s unusual and if it’s man made, we need the government to pay. If the government broke it, they need to fix it.

I just think there needs to be a Manhattan Project to deal with the tick-borne diseases. If they had been forthright in the beginning when the epidemic was in a small circle, just like with COVID, they could’ve contained it, but now it’s really big, and it’s going to be a multifaceted public health effort to get it under control.

It would really help save research dollars to know what pathogens were released in what areas and if the military had developed vaccines for their own soldiers that we could use now.

Also there’s just no good scientific studies on mixed tick-borne infections. I mean, I think these Army researchers, they released one pathogen, one insect, and they didn’t think about what would happen when it was released in the environment and it mixed with all the other natural diseases, so we have what I call a germ gangbang. A person is bitten by a tick and there’s no road map for the frontline clinicians on what these symptoms look like. What’s the order you need to treat them in? Sometimes you need to beat down the germ load in a very slow way. You can’t just blast people with antibiotics; all the carcasses of toxic bugs will give you sepsis and you’ll die of toxic shock. We need more research on the protocols that will get the germloads down in people so that their own body can heal.

Can you talk about where this is going now, what your work looks like?

So, the book was optioned after it came out, and that’s been in pre-production for a year and now it’s being pitched [to the streaming services]. So I’m helping out with that. There’s certain things I would love to wrap up [with the book] and have closure and more proof, so I continue to work on that.

And then, along the way, I had to be focused to get the book done, but there are just so many other interesting Cold War stories of crimes against humanity that are affecting health now, so I would like to write another book in the Cold War space.

I hate to make this joke, but I will anyway: it seems you were “bitten” by the topic.

Have you read “Baseless”? [By Nicholson Baker]

Not yet! But soon!

I think this work is hard on spouses of the people obsessed with these projects. I read the book and he spent 10 years trying to answer the question, did we use biological weapons on our enemies? I only spent five years. I just feel like I can pull that up to my husband and say, “See, there are other people like me.”

It was sort of like a diary. Like, “I rolled around with the dogs in bed and then I filed FOIAs.” To me it captured my life perfectly for five years. You just have to go in and out of the searches because it’s so mind-numbingly infuriating and you can’t believe it’s this broken and nobody knows about it. I’m learning new things I didn’t know because he did deeper dives on some things that I just glossed over.

I look at [this kind of investigation] like working on a 100,000-piece puzzle. You just get little pieces here and there, but in the meantime, real life is going on and you have deadlines and you’re working for the man or whatever to pay the bills. So it takes a while, and it takes years for some of these FOIAs to come back, and it’s information you can only get there.

The thing I love is the secret allies I have now in this space because we’re all sort of - we just realized this is an untold story because of the obsessive classification of all these documents.

If we released these records on the many accidents that happened in the Cold War, we can learn from it and say, “Oh, well, you know, we tried that and that didn’t work. Let’s not do that again.”

The point that Nick Baker makes is that there is no reason that 50 years after we shouldn’t just be releasing these. It would save government dollars for all these poor FOIA filers, and we need to know and learn from history for this.