As the delta variant ran rampant this summer, Missouri officials pleaded with the federal government to allow a $100 gift card program to incentivize COVID-19 vaccines. But months later, just 20 of the 115 eligible local health departments have opted into the vaccine incentive program. The results come as part of a joint investigation by The Missouri Independent and the Documenting COVID-19, a project of MuckRock and the Brown Institute.

Less than $1.8 million of the $11 million allocated for the initiative has been distributed.

And while the exact number of gift cards handed out is unclear, several of the departments that opted in say they’ve only handed out a fraction of the upwards of 15,000 gift cards that could be purchased.

One additional department may participate in the program; their participation is pending as of Wednesday.

In Adair County, just 15 of the estimated 740 cards had been used as of mid-November. Less than a quarter of the 272 gift cards the Joplin City Health Department was approved for have been distributed.

And in the most visible success story, in hard-hit Springfield and Greene County, many of the nearly 1,000 gift cards issued went to children between the ages of 5 and 11 — not the vaccine-skeptical adults the program was originally intended for.

Missouri’s experience with vaccine incentives is mirrored in dozens of other states that have experimented with cash lotteries: The programs’ net impact on vaccination rates have been low, experts say, and initiatives have been met with distrust from some communities who view the incentives as a form of government-sponsored bribery or worse.

In Carter County, in the Ozarks, opposition to the program was so fierce that a planned vaccination drive with the gift cards was canceled.

“So many parents and community members were upset, we were not allowed to hold the vaccination event at the school,” said Michelle Walker, the county health center administrator, adding that they had successfully hosted three previous COVID-19 vaccine clinics with the school district.

Since Sept. 30, just 85 gift cards have been issued out of the 396 the county received funding to purchase.

The actual logistics of the incentive program, which was first announced in late July, fell to local public health agencies across the state.

About $752,200 has been issued to purchase the gift cards, along with over $990,000 to cover operational costs for the agencies, Lisa Cox, a spokeswoman for the state health department, said Wednesday.

State officials had high hopes for the gift card program.

Representatives for the governor’s office and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did not respond to requests for comment regarding the incentive program’s impact and whether efforts will be taken to boost participation.

Former acting Department of Health and Senior Services Director Robert Knodell wrote in a mid-July email, obtained through an open records request, that the program would “take a big swing at hesitancy.” Missouri leaders urged federal officials to allow for the $100 maximum cash program, rather than a previously-announced cap of $25.

Now, as concerns over the omicron variant first identified in South Africa prompt renewed calls for vaccination drives, the impact of the ongoing incentive program at a local level seems minimal — at best.

In a statement Wednesday, Cox said DHSS knows monetary incentives are not “the silver bullet” that will persuade every Missourian to get vaccinated, but it’s an available tool worth using.

“For those it is impacting, the vaccination may have saved their life or the life of a loved one. Every person vaccinated lessens the opportunity for the virus to spread further,” Cox said. “We will never truly know the full impact of incentives and other efforts to encourage widespread vaccination. It can’t hurt to try.”

‘A complete nightmare’

For dozens of health departments that didn’t opt into the program, officials said distributing the gift cards would have been an additional task that already-overwhelmed staffers simply couldn’t handle. It was a burden that some local health departments warned state officials of back in August when they expressed early concerns with the program.

“If the state had made it an easier process for us at the local level, it would’ve been great. But we were going to have to do all the purchasing of gift cards and the keeping track of everything, and it was just going to be a complete nightmare,” said Kandra Counts, the administrator of the Shannon County Health Department in southern Missouri, later adding: “We can barely keep up with COVID cases, let alone manage a program like that.”

For some, it was simply an issue of timing. While the local incentive program was first announced in late July, it didn’t get off the ground until after federal approval for a $100-maximum for gift card incentives was finalized in August. From there, departments still had to have their plans approved by the state and receive the funds to purchase gift cards.

With funding for the incentive program ending Dec. 31, the time it would take to receive approval from both the state and the Columbia City Council would only allow about a month for the Columbia/Boone County Department of Public Health and Human Services to implement the program, said spokeswoman Sara Humm. Gift cards already received can still be issued past Dec. 31, local health departments said.

Others expressed skepticism about whether the cards could truly make a dent in Missouri’s stubbornly-low vaccination rate, which is just above 51% and ranks among the bottom 15 states in the country.

Nationwide, unvaccinated Americans are “disproportionately Republican,” according to surveys from the Kaiser Family Foundation and other research organizations, said Ashley Kirzinger, an associate director for the foundation’s public opinion and survey research team. As a result, public health departments in conservative areas — such as rural Missouri — may believe vaccine incentive programs would have limited impact in their communities, she said.

“People don’t want to feel unfairly pressured to get a vaccine,” she said. “So a public health department trying to maintain credibility with its community may not want to feel like they are coming off as pushing something that a large segment of their immediate population thinks is unsafe.”

Health agencies that chose not to participate in the gift card program echoed the concern.

“County taxpayers have expressed that that’s not where they wanted their tax dollars to go,” said a spokesperson from Jasper County’s health department. “So we chose not to (opt in).”

Perhaps even more problematic for the program is the perception that the gift cards could be viewed as a form of bribery.

In Knox County, in northeast Missouri, many of the doses administered this fall have been booster shots, said administrator Lori Moots-Clair, and just 156 gift cards have been distributed. On their own, the cards have not made a significant difference in motivating people to get vaccinated — and might have pushed some people away, Moots-Clair said.

“I can’t say that people are spreading the word and coming in and saying, ‘Hey, I want that card,’” she said. “If anything, it made people appear angry when we first started giving them out.”

In nearby Clark County, health department administrator Evelena Sutterfield’s desire to both increase her county’s vaccination rate and direct the funds locally outweighed the pushback from locals.

“There were a lot (of people) that felt it was a bribe, and people that have already been vaccinated that they weren’t going to get it,” Sutterfield said. “So I have a lot of people in my community that were upset that we did this.”

Mixed success

Among the 20 local health agencies that opted into the gift card program and have already received funding, some found that the incentives were, in fact, pushing people to get their COVID-19 shots — though confusion abounded about topics such as booster shots and eligibility for children.

Out of at least 1,700 gift cards that The Independent and Documenting COVID-19 project’s survey found were distributed, 991 were distributed by the Springfield-Greene County Health Department — many of them at a vaccine event on November 20.

“Based on our experience, there’s no question that this $50 is making a big difference and motivating people to get their vaccines now,” Cara Erwin, communications and outreach manager at the Springfield-Greene County Health Department, said during an interview the Monday following the events.

Many Springfield residents vaccinated at the events were children in the 5 to 11 age range who had recently become eligible for Pfizer shots, Erwin said. But some parents and grandparents of those 5 to 11-year-olds who hadn’t received the shots also came in to get their first doses.

In addition to the gift cards, the department auctioned off $15,000 in prizes for newly vaccinated residents, donated by the Community Foundation of the Ozarks.

Like Springfield, in Adair County, the health department has paired its gift card program with a drawing for four winners to each receive $250 that was funded by private donation. For every 10 new participants in the incentive program, another drawing will be held. For Jim LeBaron, the administrator of the health department, it’s worth trying anything that could spur an uptick in vaccinations.

“If we get 10, 20, 25, 50 people that get vaccinated because of the incentive program, I think it’s worth it,” LeBaron said.

Health departments are permitted to give away $50 gift cards when county residents get their first or second COVID-19 shots, but not booster shots.

Washington County has distributed 267 gift cards to newly vaccinated residents as of Nov. 22. Department administrator Shawnee Douglas said the cards have been helpful, particularly in motivating younger residents. But she wishes she could also distribute the cards to people receiving their booster shots.

“It’s just kind-of sour,” Douglas said, of not being able to offer gift cards to those getting a booster. “And I get that. I don’t like it either.”

Vaccine incentives can serve as a form of stimulus payments for Americans, said Armando Meier, a research fellow at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland who contributed to a study showing that vaccine incentives had a positive impact for a Swedish population.

The payments both contribute to public health goals and promote spending in the local economy, he said. This was true for some of Missouri’s health agencies, which purchased gift cards from local businesses.

“It’s not simply about avoiding hospitalizations and deaths,” Meier said, “but actually that this money is useful for people anyway.”

In Washington County, the health agency obtained gift cards through the local chamber of commerce. About 68% of cards were for local grocery stores and the remaining 32% were for local gas stations.

“I’m hoping [the gift cards] will also help promote our local businesses and support them instead of just going into some big conglomerate like Walmart,” Douglas said.

In Dent County, more than two thirds of students in some of its school districts were enrolled in free-and-reduced price lunch in 2020, according to state data. With food insecurity an issue facing the area, the health department decided to select a locally-owned grocery store, Country Mart, for its gift cards, said Zachary Moser, the department’s administrator.

Out of the 532 gift cards the department received funding for, about 110 gift cards have been given out as of Nov. 15, Moser said. He hasn’t heard anyone cite the gift card as the catalyst for getting vaccinated, but he thinks it helped tip the scale in that direction for some.

“Most of the time, people’s concerns are not something that’s going to be overcome by $100,” Moser said. “But I do think that as a measure of mitigating the impact overall of COVID, I think it’s a big deal. We had a lot of people lose income and all that from the pandemic, and so I think this will go a little ways to at least helping us recover from that as well.”

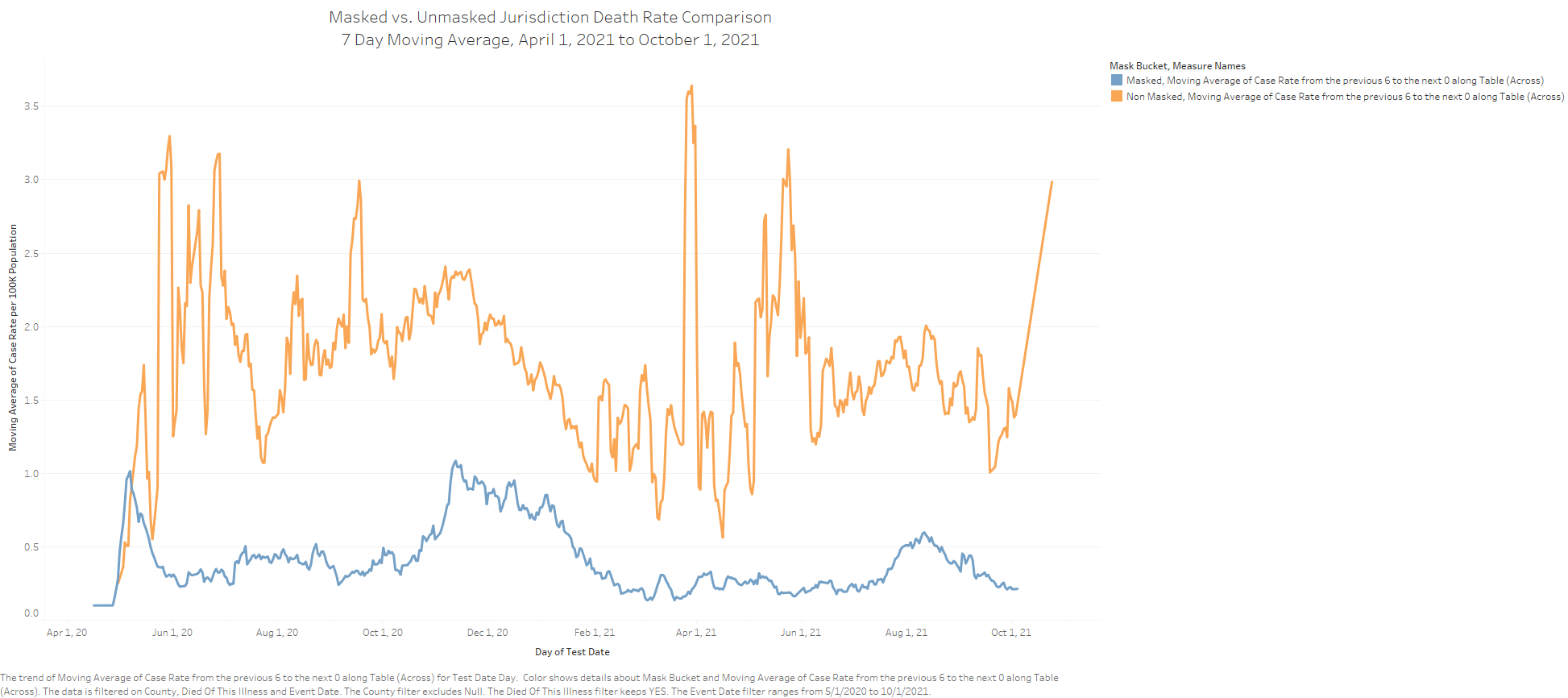

Similarly, the Clinton County Health Department, which received enough funding for 250 gift cards, is at the “kitchen sink” phase of their vaccine rollout, said department administrator Blair Shock. Shock and his colleagues are trying to do anything to convince people to take a shot. Of the more than 80 COVID-19 deaths in the county, all but one were among residents who weren’t fully vaccinated, he said.

“We’re not pushing this because it’s our job. We’re not pushing this because we’re toeing the line here. We’re pushing this simply because this is our community,” Shock said, “and we want to reduce the amount of suffering and the amount of death that we see within the community.”

Missouri fits into national pattern

Ohio was the first state to implement a lottery for vaccinated residents, back in May. The “Vax-a-Million” lottery appeared to drive an uptick in vaccinations, which was touted by state and national leaders.

But Ohio’s lottery was not as successful as it seemed, researchers found in a study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association in July.

Two days before the announcement of the new Ohio lottery, the Pfizer vaccine was approved for children ages 12 and 15 and the Ohio lottery’s perceived success was likely influenced “by the nearly simultaneous release of the vaccine to adolescents,” said Dr. Allan Walkey, an associate professor of medicine at Boston University and the lead author of the study.

The lottery, simply put, “didn’t have a large effect on vaccine uptake,” Walkey said in an interview.

Other states’ lotteries similarly have not had a substantial impact on vaccination. A study examining trends in 19 states found that after governments announced new cash lottery programs, any increase in vaccination rate was “very small in magnitude and statistically indistinguishable from zero.”

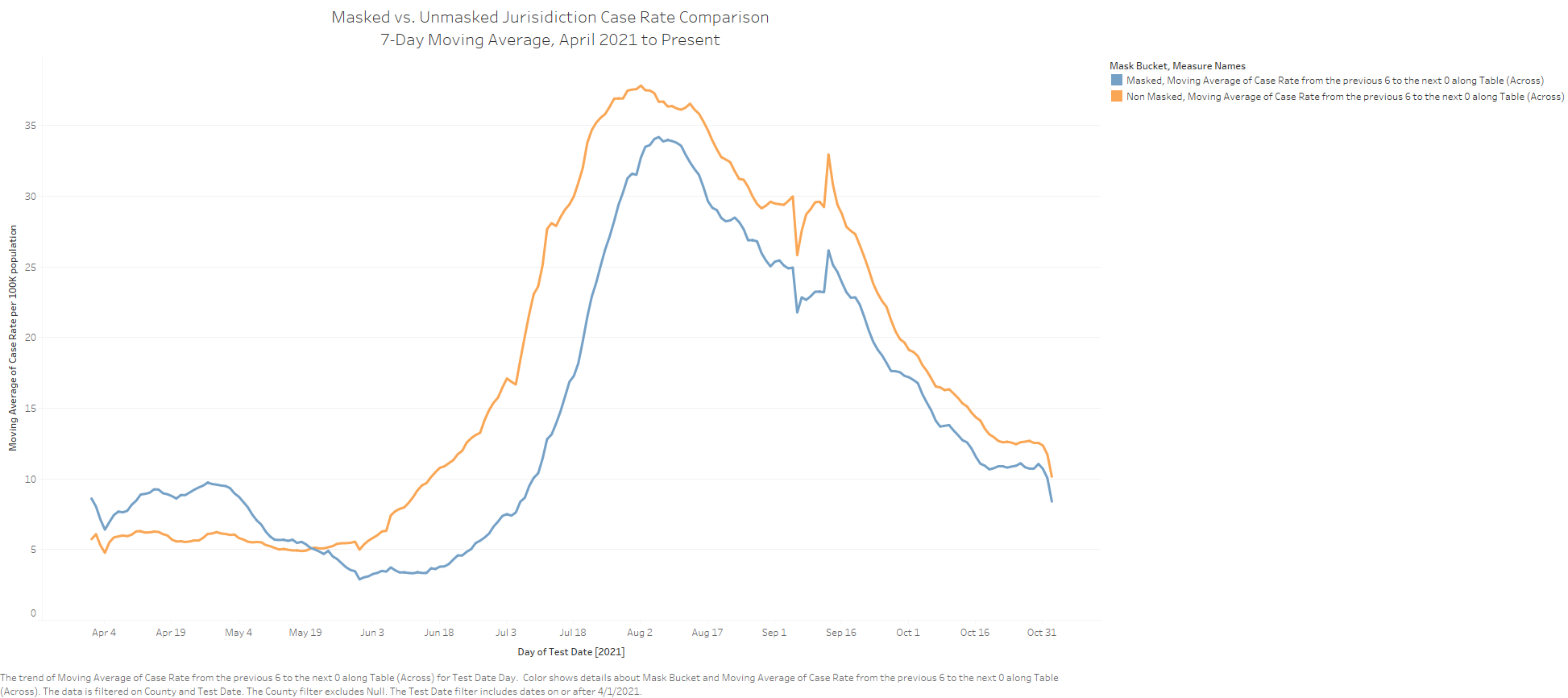

Though vaccinations increased during the summer in states like Missouri, Arkansas and Louisiana, it’s difficult for researchers to attribute these increases to vaccine incentive programs when the delta surge was devastating healthcare systems.

In late July, a Bloomberg analysis found that the undervaccinated counties facing delta were most likely to see an uptick in people going to get their first doses.

“The increase in cases and concerns about filling ICUs, and knowing someone that got really sick, or perhaps died — all of those seem to have a much bigger impact on people’s vaccine intentions” compared to cash incentives, said Kirzinger, the Kaiser Family Foundation polling expert.

In its surveys, the foundation divides unvaccinated Americans into “wait and see,” “only if required,” and “definitely not” categories. Incentives may be a measure to help convince the “wait and see” and “only if required” groups to get their shots, Kirzinger said, but the “definitely not” group is less likely to come around — especially as vaccination becomes increasingly tied to political polarization.

While Gov. Mike Parson and DHSS Director Don Kauerauf have called the state’s now-concluded vaccine lottery successful, the program coincided with the delta surge, making it difficult to evaluate.

More than 656,200 Missouri residents entered to win the state’s vaccine lottery, which ended in October and offered $10,000 prizes. But of the nearly 617,000 adults that entered, only 9%, or 57,117, got vaccinated after the lottery had been announced, according to DHSS figures.

Those 57,117 Missourians represent less than 1% of the state population.

Just over half of the state’s population is fully vaccinated as of Dec. 1, according to the state’s COVID-19 dashboard. It’s about 8% lower than the full vaccination rate for the U.S. as a whole and it puts Missouri in the bottom quarter for vaccination rates nationwide.

With lower vaccination rates, Missouri will likely have a more difficult time beating back new variants, Kauerauf told St. Louis Public Radio last month. He hopes to see Missouri’s vaccination rate rise to 75%.

“People may laugh at me for thinking it’s even possible, but I hope so,” Kauerauf said. “I hope we can get there.”

Header photo, showing vaccinations administered at The Linc’s vaccination site in Jefferson City on March 19, 2021, courtesy of Missouri Governor’s Office.