This investigation is a collaboration between Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation and MuckRock’s Documenting COVID-19 project and the USA TODAY network. Reporting by Dillon Bergin, Betsy Ladyzhets, Jake Kincaid and Derek Kravitz of the Documenting COVID-19 project; Sarah Haselhorst, The Clarion-Ledger; Ashley White and Andrew Capps, The Daily Advertiser; Rudi Keller, The Missouri Independent; Nada Hassanein, USA TODAY. Steve Myers of USA TODAY and Derek Kravitz edited.

In late January, the official death toll from COVID-19 in Lafayette Parish, Louisiana, stood at 210.

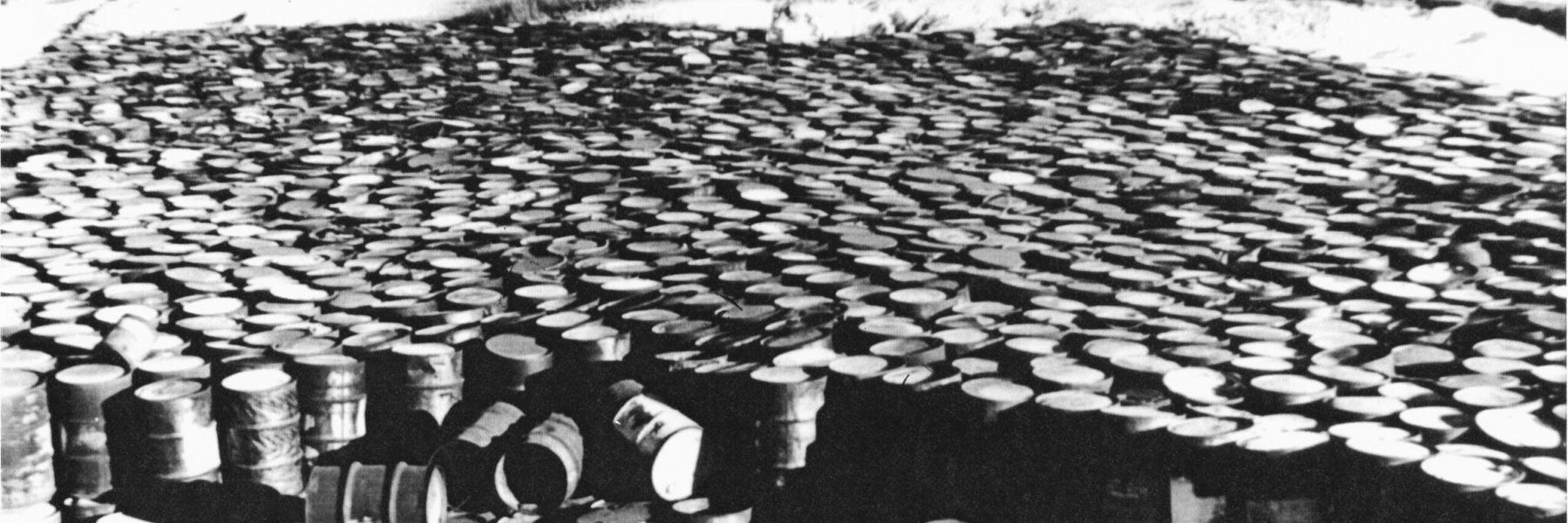

At a makeshift memorial at a local Episcopal church, friends and relatives planted small, white flags representing how many people had died. Some inscribed flags with the names of those they had lost.

But a couple hundred flags were missing. Those people almost certainly died from COVID-19, according to an examination of newly released data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but their death certificates don’t mention it. Instead, they list conditions with symptoms that look a lot like COVID-19, such as Alzheimer’s disease, hypertension and diabetes.

Photo by ANDRE BROUSSARD/SPECIAL TO THE DAILY ADVERTISER

Nationwide, nearly 1 million more Americans have died in 2020 and 2021 than in normal, pre-pandemic years, but about 800,000 deaths have been officially attributed to COVID-19, according to newly released CDC data. A majority of those additional 195,000 deaths are unidentified COVID-19 cases, public health experts have long suggested, pointing to the unusual increase in deaths from natural causes.

An investigation by Documenting COVID-19, the USA TODAY Network and experts reveals why so many deaths have gone uncounted: After overwhelming the nation’s health care system, the coronavirus evaded its antiquated, decentralized system of investigating and recording deaths.

Short-staffed, undertrained and overworked coroners and medical examiners took families at their word when they called to report the death of a relative at home. Coroners and medical examiners didn’t review medical histories or order tests to look for COVID-19. They and even some physicians attributed deaths to inaccurate and nonspecific causes that are meaningless to pathologists. In some cases, stringent rules for attributing a death to COVID-19 created obstacles for relatives of the deceased and contradicted CDC guidance.

These trends are clear in small cities and rural areas with less access to healthcare and fewer physicians. They’re especially pronounced in rural areas of the South and Western United States, areas that heavily voted for former President Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election.

Lafayette Parish, Louisiana; Hinds and Rankin counties in Mississippi; and Cape Girardeau County, Missouri, are four of the 10 counties with the greatest spike in deaths not attributed to COVID-19. In those communities, official COVID-19 deaths account for just half of the increase in deaths in 2020.

If official figures are to be believed, in Lafayette Parish deaths at home from heart disease increased by 20% from 2019 to 2020. Deaths from hypertensive heart disease, or heart ailments due to high blood pressure, doubled and are on track to remain that high in 2021.

These sudden, unexplained jumps in deaths at home – from diseases with symptoms similar to COVID-19 – point to a substantial undercount of the pandemic’s toll, said Andrew Stokes, a professor in the Department of Global Health at the Boston University School of Public Health.

Lafayette Parish’s chief death investigator, Keith Talamo, acknowledged that most people who die at home are pronounced dead over the phone. He said his office lacks the resources to test every death for COVID-19. And, in a significant departure from widely accepted death investigation practices, Talamo said he typically writes down “what the families tell us” and doesn’t push further.

In and around Jackson, Mississippi, deaths from heart attacks at home doubled in 2020 and are on pace to hit a similar level in 2021. The Rankin County coroner said he wrestles with family members who first argue against citing COVID-19 on death certificates, then reverse course when they learn that the federal government pays for burials of people who die from the coronavirus.

And in Cape Girardeau County, Missouri, coroner Wavis Jordan said his office “doesn’t do COVID deaths.” Jordan does not investigate deaths himself. He requires families to provide proof of a positive COVID-19 test before including it on a death certificate.

So far in 2021, he hasn’t pronounced a single person dead from COVID-19 in the 80,000-person county.

Photo by PATRICK SEMANSKY, AP

Errors on death certificate errors aren’t limited to COVID-19. For example, the CDC puts the number of drug- and alcohol-induced deaths in Maryland 21% higher in 2020 than state figures. Nearly a third of all deaths in the U.S. from “senility” in 2020 and 2021 were registered in four counties in and around Tampa, Florida. The regional medical examiner said his office isn’t responsible.

The Documenting COVID-19 project and the USA TODAY Network spent months reviewing CDC mortality data at the county level. They compared those figures to models developed by the CDC and a team of demographers at Boston University, collected death certificates and documents, and interviewed more than 100 medical examiners, coroners, public health experts, families and policy-makers. Stokes and his team worked with the journalists on this project, providing models of expected deaths in every U.S. county and identifying areas of potential underreporting of COVID-19 deaths.

The nation’s struggle with recording COVID-19 fatalities underscores a truism about death in the United States: Where people live and die has a lot to do with the accuracy of their death certificate. Some deaths are investigated with state-of-the-art technology and expertise. Others don’t go beyond a phone call from the family.

“Our death investigation system urgently needs both oversight and standardization of training and procedures,” Stokes said. “It’s hampered our ability to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, and leaves us unprepared for future public health emergencies.”

The essential, unreliable death certificate

When people die, their death and its causes must be certified and registered according to state laws. A death certificate is the last legal document someone leaves behind, and one of the most important. But they can be as unreliable as they are essential.

In Lafayette Parish, COVID-19 was listed as the underlying cause of death in just 134 fatalities in 2020, even though there were 419 “excess deaths” – the number of deaths that exceed a normal, pre-pandemic year. The gap between these two numbers means hundreds more people likely died of COVID, researchers say.

Meanwhile, deaths attributed to diseases that are often tied to COVID-19 increased. Deaths at home from hypertensive heart disease, diabetes and Alzheimer’s all increased 30% or more in 2020. Those deaths, especially those that weren’t properly investigated,make up at least some of Lafayette’s missing COVID deaths, according to experts.

Especially concerning are deaths in the community attributed to nonspecific causes, known as “garbage codes.” For example, 40 people in the parish who died at home since 2020 have been certified as dead of “heart failure, unspecified.”

Photo by GERALD HERBERT, AP

“If a clinician is certifying a death this way because they truly do not know what caused the death, they should get an autopsy to find out,” said Dr. James Gill, president of the National Association of Medical Examiners and Connecticut’s chief medical examiner.

Heart failure, cardiac arrest and senility are all garbage codes. They should rarely, if ever, be cited as an underlying cause of death, said Gill, who reviewed causes of death listed on death certificates during the pandemic.

These three codes appear more frequently on death certificates in places with the largest jumps in deaths not attributed to COVID-19.

Talamo, Lafayette Parish’s chief medicolegal investigator, said he doesn’t think COVID-19 deaths are going uncounted, instead blaming suicides or drug overdoses.

But the CDC data, collected from his own office, and data he provided the Documenting COVID-19 project undercuts that. In 2020, deaths from accidents, homicides, suicides and drug overdoses exceeded the prior year by 45. Deaths attributed to natural causes jumped by 260.

Talamo, a full-time, trained death investigator, said he checks with a state registry to see if people who died had a positive COVID-19 test. If so, he includes COVID-19 on the death certificate.

But he’s the only full-time employee in the coroner’s office in Lafayette Parish, one of the largest in the state. His office handles a lot of deaths at home, and most are pronounced dead over the phone.

“We don’t have the infrastructure to go and check everybody for COVID,” Talamo said. He acknowledges that, because of a lack of testing, his office likely missed COVID-19 deaths that could’ve been identified with enough time and resources.

Ken Odinet, the Lafayette Parish coroner who was reelected as a Republican in 2019 and oversees the office, said he thinks the current system of confirming COVID-19 deaths works.

The ‘scarlet letter’ of COVID

William Clark, the East Baton Rouge Parish coroner and the president of the Louisiana State Coroners Association, said he has three requirements in order to put COVID-19 on a death certificate: The patient must have shown symptoms of respiratory illness, tested positive for the coronavirus and died of the respiratory illness.

Many families, he said, simply didn’t want their loved ones to be pronounced dead from the coronavirus.

“In 2020, getting COVID, or dying from COVID, or being a family member that had COVID, was a scarlet letter,” he said. “It was shunned.”

Limited testing in 2020 could account for some uncounted COVID-19 deaths, Clark said. And many people were hesitant to get tested.

“I can recall a guy who had COVID symptoms; his X-ray looked like COVID because I saw it. And the guy says, ‘You’re not sticking a swab in my nose,’ and he died a few days later. That guy had COVID, but I didn’t call it COVID,” Clark said. “He was not given a postmortem test. After he died, I think he still has a right to those wishes.”

Clark is wrong, according to the CDC, which tells coroners they can attribute a death to COVID-19 even without a positive test, as long as they use their “best clinical judgment.”

The coroner defended his reasoning, saying CDC guidelines are “just that – guidelines. They are not laws.” He said many families want COVID-19 listed on death certificates for financial reasons. “The number of phone calls we receive weekly in an attempt to defraud the government is astounding,” he said.

Statewide, 4,644 of the spike in deaths during the pandemic were not attributed to COVID-19, according to the CDC.

A spokesperson for the Louisiana Department of Health acknowledged the gap. Deaths at home “do make up a substantial portion of the overall non-COVID-19 increase,” Kevin Litten wrote in an email.

Still, Litten wrote, it’s difficult to know whether deaths at home increased because people died from the virus or because they avoided hospitals and died of something unrelated.

‘No one wants to be a coroner’

After another long day in November, David Ruth, the elected county coroner in Rankin County, Mississippi, counted how many calls he had gotten on his cell phone that day: 74.

Ruth, elected as a Republican in 2015 after more than three decades as a police officer, never could’ve planned for the change that 2020 would bring to his job. He once prided himself on posting his cell phone number on the government website; now he has more calls than he can answer.

“No one wants to be a coroner,” Ruth said.

Photo by BARBARA GAUNTT, CLARION LEDGER VIA USA TODAY NETWORK

Coroners are one part of the patchwork system of death investigations in the United States. When people die in a hospital or health care facility, a physician usually reviews their medical history to determine the cause of death. When someone dies at home or in an accident before being brought to a hospital, a medical examiner or coroner like Ruth investigates and determines the underlying cause of death.

Rankin County lost 140 people to COVID-19 in 2020. But deaths surged by an additional 209 compared to a typical year.

Deaths in Hinds County, which neighbors Rankin and is home to most of the city of Jackson, mirror the trend. Official COVID-19 deaths account for just half of the spike in deaths in 2020.

The Hinds County coroner, Sharon Grisham-Stewart, did not respond to requests for comment.

Some families have told Ruth they don’t believe in COVID-19 and don’t want it on death certificates. Others have said they want people to know the virus’ death toll.

He said he’s even been confused by inconsistencies between his office’s death figures and those reported by the county health department.

“It got to the point the health department was reporting one number and I was like, ‘I don’t know where they got that number.’ Sometimes it was more, sometimes it was less,” he said.

‘COVID-19 can mimic an awful lot of diseases’

Mississippi has the country’s highest COVID-19 death rate, with 1 in 285 people dead from the disease. But in September 2020, State Health Officer Dr. Thomas Dobbs said the death toll of about 2,700 at the time was “almost certainly” low.

The state also saw some of the nation’s highest increases in deaths attributed to natural causes, especially heart and lung disease, from 2019 to 2020, according to CDC data. Deaths from Alzheimer’s, hypertensive heart diseases and dementia all increased about 20% or more.

Photo by ANDRE BROUSSARD/SPECIAL TO THE DAILY ADVERTISER

These increases may be key to understanding which COVID-19 deaths were misclassified.

“COVID-19 can mimic an awful lot of diseases,” said Dr. Marinelle Payton, a physician and professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Jackson State University and director of the university’s Center of Excellence in Minority Health and Health Disparities.

“In a state like Mississippi that has low economic resources, those resources are not going to be utilized for testing people that have already died,” she said.

Early in the pandemic, COVID-19 overwhelmed health care facilities, leading to reporting errors.

“As someone who has been in the hospital in the middle of the night and who has had to fill out a death certificate, I can tell you that it is sometimes difficult to rely upon what is written regarding cause of death,” said Dr. Lionel Fraser, Central Mississippi Health Services’ chief medical officer.

“Now consider what happens with deaths at home without the resources of a chart, history or diagnostic tests,” he said. “Errors may occur and these data may be skewed.”

‘None of the things on her death certificate was her cause of death’

A combination of fear and misinformation compounded Mississippi’s problem with access to health care, said Dr. Paul Burns, a social epidemiologist and professor of population health at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. In Hinds County, 26% of residents live below the poverty line and 15% are uninsured, both well above the national average. The county is 73% Black.

“Even before the pandemic, communities of color had concerns about whether or not the health care system was really addressing their needs,” Burns said.

Payton said she’s familiar with inaccurate death certificates not just as a physician or a professor, but as a family member. When her sister died recently, Payton realized the death certificate was wrong.

“I was absolutely outraged. Because none of the things on her death certificate was her cause of death,” Payton said. Over the years, “the same thing happened with my mother, my father, and my brother. All of their death certificates are incorrect.”

The Mississippi State Department of Health said in an October advisory that it “has been aware of mortality increases that exceed COVID deaths.”

When presented with findings from the CDC data about increases in deaths at home, especially from heart and lung disease, department spokesperson Liz Sharlot said in a written statement: “We don’t have sufficient information to answer these questions. It would take a lot of speculation and that is all it would be – speculation.”

Undertrained and under-resourced

In Cape Girardeau County, Missouri, the coroner has not pronounced a single person dead of COVID-19 in 2021. “When it comes to COVID, we don’t do a test, so we don’t know if someone has COVID or not,” said Jordan, the coroner.

The 113 deaths officially blamed on COVID-19 in 2020 account for just half of the county’s 226 excess deaths that year.

Meanwhile, deaths at home attributed to heart attacks, Alzheimer’s and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease increased. In 2020 and 2021, death certificates say 35 people died of “cardiac arrest” or “cardiac arrhythmia,” both of which are garbage codes.

Jordan, a Republican who took office in 2021, had no medical training or experience handling the dead before his election. In an interview, Jordan said he requires families to provide proof of a COVID-19 diagnosis before he puts it on a death certificate. That goes against accepted CDC practice that allows those signing death certificates to take into account symptoms of the virus and the patient’s medical history.

“You know, I have to go by what the family says,” Jordan said. “The family can tell me all they want that this person had COVID, but I just can’t put it on there unless I have some type of proof.”

Finding that proof is supposed to be the job of death investigators like Jordan. The official guidance that the CDC has given coroners is not to rely on families, but to investigate each case to the best of their ability with all the tools they have.

The CDC even tells coroners they can certify COVID-19 as the cause of death without a positive test when there’s strong reason to believe that the person died of COVID, such as deaths during nursing home outbreaks in which everyone wasn’t tested before they died.

A spokesperson from the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, Lisa Cox, said the department is aware of an increase in deaths beyond those tied to COVID-19. She said the agency follows CDC guidance for death reporting and makes that guidance available to localities.

Other Missouri counties with coroners describe a very different process than the one in Cape Girardeau. Across the state in Buchanan County, a review of a patient’s medical file, or a chart review, is performed for every death. If the death is unattended – such as a death at home with no one else around – and it’s unclear why they died, the body is sent to a forensic pathologist in Kansas City for a full autopsy.

“We don’t reach out to family and find out,” said Richard Shelton, a medical investigator for the Buchanan County Medical Examiner. “We want to make an outside, independent investigation.”

Patchwork system of death investigation in the U.S.

The training, expertise and resources of the people who sign death certificates in one county can be wildly different from the county next door. Some states have coroners in each county; others have a statewide medical examiner’s office. And some, like Missouri, have a mix of both systems.

A third of Americans are served by coroners, who typically work in rural areas and smaller cities – often on low pay and with little resources. Just 14% of coroner’s offices in the country are accredited by one of two national groups, according to a recent Department of Justice report. On average, a coroner’s salary ranges from $17,000 to $38,000 a year, while experienced medical examiners and trained forensic pathologists in urban areas make two to 10 times more.

Medical examiners are appointed while coroners are usually elected, which can come with political pressure.

“It really comes down to the resources available to the office,” said Dr. Bob Anderson, the chief of mortality statistics at CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. “Particularly early in the pandemic, a lot of the medical examiner/coroner offices didn’t have tests for postmortem. So they had to make assumptions based on the available information.”

To a lesser degree, some elected coroners – lacking formal training or clear guidance on how to determine cause of death – let politics dictate their decision-making.

Last summer, Documenting COVID-19 reported on a coroner in Macon County, Missouri, who said he left COVID-19 off at least a half-dozen death certificates when another major factor could be justified as the sole cause of death.

“There is no standardized training in the United States to do it right,” said Ali Mokdad, a professor of health at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington.

When asked whether the CDC should provide medical examiners and coroners with clearer guidelines to standardize death certificate reporting, Anderson said the CDC works with state vital records offices, not counties. He deferred to national professional organizations and the professional opinion of individual medical examiners.

“We’re a statistical outfit,” Anderson said. “We can’t very well go around telling medical examiners and coroners – knowing that they don’t report to the federal government in any way – telling them how to do their jobs.”

Mokad, who worked as a senior epidemiologist at the CDC, disagrees. “The CDC can do better. Let’s be realistic. … The CDC tells every state, every county, it has to do certain things. So why stop at the causes of death?”

Missed opportunities to intervene

In Lafayette Parish, the COVID-19 pandemic was handled like a minor inconvenience in the months after the first local cases were reported. Despite recommendations from state and regional public health officials, local authorities largely failed to enforce statewide mask mandates during the 13 months they were in place.

A push for an additional mask mandate in the city of Lafayette in February met with widespread opposition, with more than 2,000 residents calling the city council after the mandate was proposed. The proposal was sponsored by Councilman Glenn Lazard, who was diagnosed with leukemia in 2019.

“Our response to COVID in Lafayette gets an F,” Lazard said. “We basically refused to follow the governor’s mandates, saying that it needs to be enforced by the state. We’ve never enforced the occupancy limits, primarily in nightclubs, and so forth and so on. It was very frustrating and very disappointing.”

Experts say an incomplete picture of the coronavirus’ toll can lead people to take preventative measures less seriously. If communities don’t have accurate data on how many of their residents are dying, they are less likely to wear masks and avoid big groups indoors.

Lazard said he believes his mask mandate would have failed even if the true number of deaths from COVID-19 had been known. “This was turned into a purely political issue, as opposed to a health care issue,” he said.

Enbal Schacham, a professor of public health at Saint Louis University who studies how people respond to information about the virus, said inaccurate death figures contribute to the nation’s struggle to respond.

“Underreporting of COVID deaths actually makes us think that we’re not in control of any of it,” Schacham said. “And I do think we are, in effect, choosing not to prevent it.”