This story was originally published by The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom covering gun violence in America. Sign up for its newsletters here.

I spent most of this year reporting on Illinois’ Victim Compensation Program , exploring the questions of whether it worked and who it is — and isn’t — working for. The program is designed to reimburse victims of violent crime and their families for expenses related to injury. Every state in the country has a program like this, all funded in part by the federal government, although different states operate their programs differently.

I became interested in this subject after a group of Illinois anti-violence and victim advocate organizations published a 2019 report expressing concern about the program, including extended wait times for applications and services that exclude the populations most vulnerable to crime. The problems are not isolated to Illinois. Since our story published in early July, people from places like Georgia and Minnesota have shared their experiences struggling with victims compensation programs.

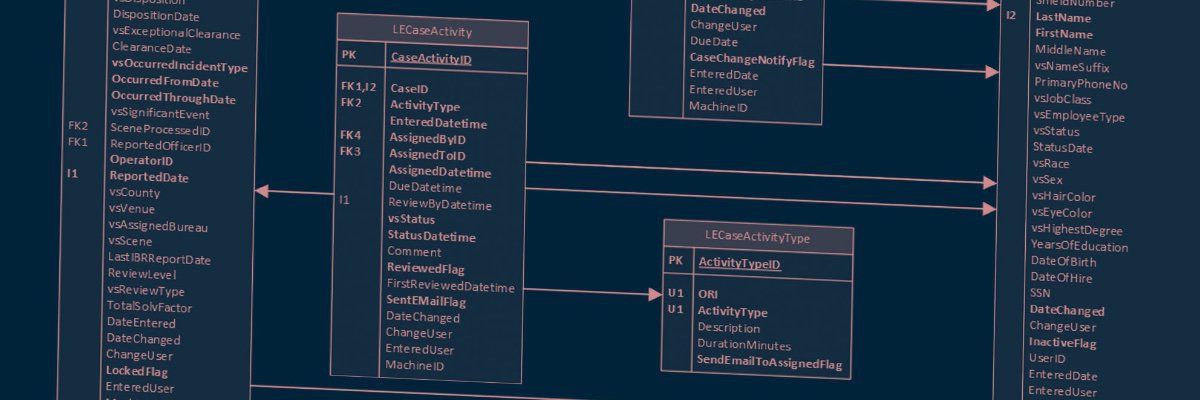

For this investigation, published as part of my “Aftershocks” series on the experience of surviving gun violence in Chicago, I looked at nearly 15,000 claims the state processed between 2015 and 2020. Working with Daniel Nass, our associate editor, data and graphics, I found less than 4 in 10 applicants in Illinois received any reimbursement. To report this story, I filed several Freedom of Information Act requests asking for data and staffing records, read historical reports, and spoke to dozens of people. I learned that in addition to few people receiving the funds, many have no idea the program exists and can offer them financial support.

Read on to learn how you can report on the program in your area.

What you should know about victims compensation

Crime Victim Compensation, or CVC, is an incredibly complicated program. Although it uses federal funding, individual states decide how to run their individual compensation programs. For example, in Illinois, there are four agencies involved in processing claims from beginning to end; other states may rely on just one government group. Contact your state program directly to understand how the program works and ask them to walk you through the process. This is the first thing you need to know before you can strategize about the types of records you’ll need, and how you might be able to find them.

Since states receive federal funding for CVC, they are required to report annually on how they spend that money. You can find states’ performance reports to the federal government here . In these reports, you’ll find demographic data on victims’ age and race, as well as documentation on how the program is working. Keep in mind that this reporting runs along a fiscal year, and not a calendar year.

Questions to ask about victims compensation

- Are there any annual reports or assessments published, internally or publicly, about the program’s progress?

- How many people work in the organization administering the program? Of these, how many are specifically trained to analyze and vet compensation claims?

- How does the state ensure that its record-keeping is accurate and up-to-date?

- Are there any trends related to the number of people applying to the program over the years? If applications are decreasing, what might be causing the downturn?

- Lastly, your state program might offer training to local organizations showing them how the CVC process works. Ask if you can sit in on one of them.

Asking for records from your state

Once you know how victims compensation works in your state — including what officials are telling the federal government about how it’s all going — you’ll want to get even more detailed information. You should start by asking for data on the program. Chances are, program representatives will ask you to write a FOIA for the exact type of information you’re seeking.

I recommend including the following in your requests — feel free to borrow language from mine:

- Applicant name

- Application number

- Applicant age, race, sex

- Victim age, race, sex

- Type(s) of crime the claim is for

- What the reimbursement is for (e.g. funeral costs)

- Date the application is submitted

- Date the applicant was entered into your state’s case management system

- Date an analyst made a decision on the claim

- Date the money was dispersed to the applicant

- Monetary amount the applicant requested and how much was awarded

- Whether the payment was dispersed via check or electronic deposit

Above, you can see the FOIA requests I filed for this story. Since most states offer paper versions of the application, I asked for almost all of the information that applicants provide on these forms.

If you are able to get certain information through a data request, ask for copies of the actual application and highlight the specific pages or sections you want. (See below.)

Remember to ask for any reviews, reports, or memos that would show any changes, problems, or complaints the program might have faced. Since many of these programs have existed for decades, I would ask for at least three years of data to start.

If you want to learn more about how Daniel and I conducted our analysis, read our behind-the-scenes story .

The potential challenges with reporting

If multiple agencies operate the program in your state, you might hear conflicting information about which records are available through FOIA . It’s important to speak with everyone to understand how the program operates and what records you can receive. If your state tells you that race or gender information isn’t available, for example, keep in mind that the federal reports require states to report this demographic data.

If your state created its program before the passage of the federal Victims of Crime Act in 1984, the record-keeping might be shoddy. For example, your state might not be able to provide a data dictionary explaining what, exactly, the fields in the data they send back to you mean. If this happens, ask them about field definitions over the phone so you can accurately analyze the data. I also recommend running your analysis and findings by the agency or agencies once they’re complete, to make sure you haven’t misunderstood something.

Learn as much you can and learn as you go

An important note on the data analysis: There are multiple reasons a claim may not be awarded a reimbursement. In Illinois, there’s a category called “award no pay.” This means that an applicant is technically eligible to receive funds but the money was not reimbursed directly. I found the most common reason for this in Illinois was also due to an applicant not turning in enough paperwork. In other words, there are thousands of people who are still eligible to receive the reimbursement, although they may not know it because of the way the claim is labeled.

Aside from the data, speak with advocates and activists about their experiences with the program. They can likely connect you with people who have applied.

Another major thing to look out for is awareness. People can only apply, and benefit from compensation, if they know the program exists — and how it works. We’ve found it is common for families to not understand the minute details of the program. I learned a lot from walking them through it and asking them what they struggled with during the application process.

We’re excited to see the stories you report. Please share them with us once they publish. If you have any questions, don’t hesitate to email me at victimscomp@thetrace.org.

Read more about the analysis for this reporting at The Trace, and sign up for their newsletter. Have you tackled a major public records reporting project you want others to build on? Get in touch and we’d love to talk. Image via Pixabay by Oliver Menyhart.