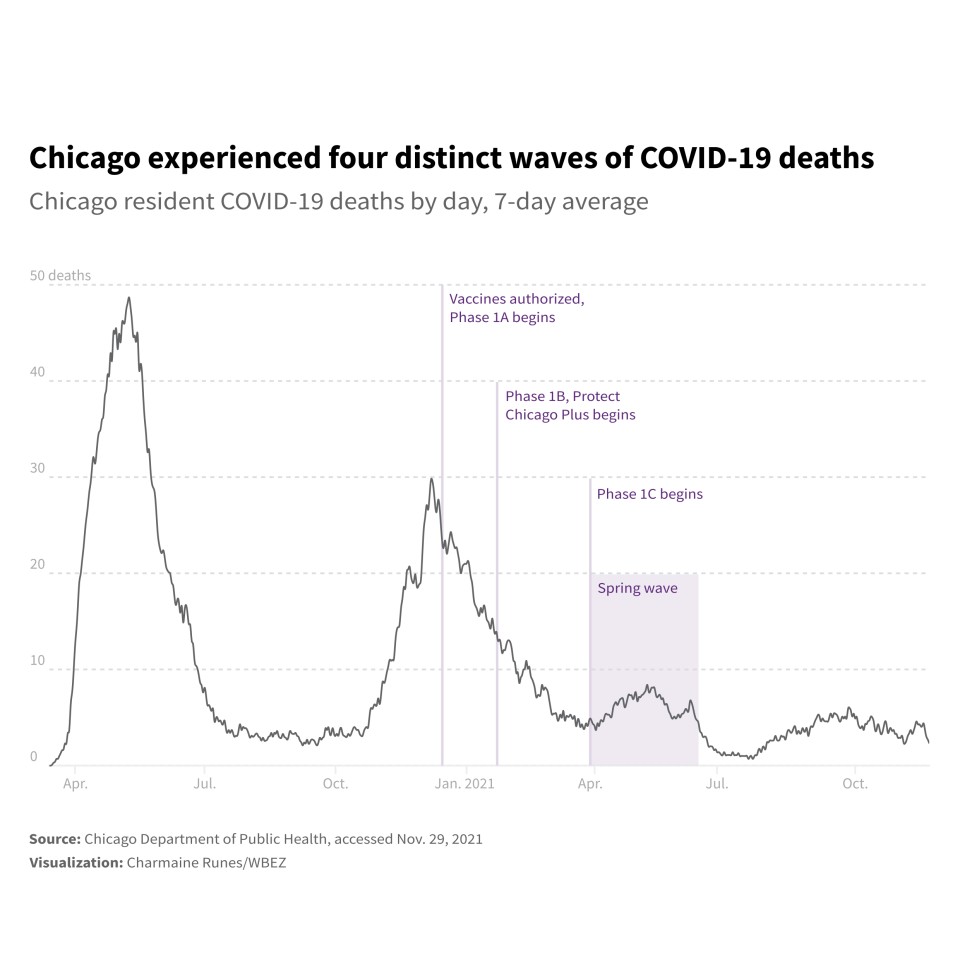

Nearly a year ago, after the first shipments of vaccine arrived in Chicago, city government rolled out a strategy to get extra doses into South and West side communities identified as most vulnerable to COVID-19.

“Equity is not only part of our COVID-19 strategy, equity is our strategy,” Mayor Lori Lightfoot said in January while announcing the Protect Chicago Plus initiative.

Since then, public health experts have collected and analyzed data over time to answer the question: Did Chicago go far enough?

According to one provocative finding, the answer is no. Even as the city celebrates a milestone – 77% of Chicagoans 12 and up, at least partially vaccinated as of late November – that number conceals a persistent divide.

New research and modeling published by the University of Chicago’s Healthcare Ethics and Allocation Lab argues the city could have gone further, suggesting that a better vaccine rollout might have saved hundreds of lives during the deadly spring wave of 2021.

Dr. Allison Arwady, Commissioner of the Chicago Department of Public Health, dismissed some of the underlying assumptions of the study and its conclusions.

“I think it’s a little bit simplistic to say that there were distribution strategies that led to those outcomes,” she said. “Everything we did was to try to decrease that inequity.”

To get a closer look at vaccination rates across Chicago, WBEZ teamed up with the Documenting COVID-19 project , a journalism collaborative started at the Brown Institute for Media Innovation at Columbia University, and MuckRock, a nonprofit that promotes government transparency and accountability through public records requests and investigative journalism. In addition to reporting on the study and interviewing public health experts on the initial vaccine rollout, the reporting team compiled various public health metrics by ZIP code and community area to measure the impacts of disparities over time.

The data highlighted significant inefficiencies in the vaccine allocation process despite the push to focus on more vulnerable community areas.

The data show how, despite the city’s efforts to improve vaccine equity, the initial rollout of Protect Chicago Plus failed to prioritize some of the city’s most vulnerable communities.The data shows how measures to improve vaccine equity amid the rollout still left some of the city’s most vulnerable communities overlooked.

Study estimates 118 deaths were avoidable

The University of Chicago study details how, despite the city’s efforts to target vulnerable communities, “white and high-income communities were often the first people to receive vaccines” across the country during the earliest phases of the rollout. By April, the ZIP codes with the lowest vaccination rates were largely clustered on the South and West sides.

“Places like St. Bernard Hospital in Englewood should have just had as many doses as they could administer. That wasn’t the case,” said Dr. William Parker, an assistant professor of pulmonary critical care medicine who is also assistant director for the University of Chicago’s MacLean Center for Medical Ethics. “The places that do exist that are serving only disadvantaged communities need to get more doses.”

Parker led the research team in analyzing where and how Chicagoans got vaccinated, and why vaccine hesitancy wasn’t the only factor in the disproportionately low vaccination rates of some of Chicago’s predominantly Black and Latino ZIP codes.

The study, “Consequences of COVID-19 Vaccine Allocation Inequity in Chicago,” estimates that 118 additional deaths could have been avoided in the spring of 2021 if the least vaccinated group of Chicagoans had the same access to vaccines as the most vaccinated group. The researchers conclude that the inequitable vaccine allocation in Chicago “exacerbated existing racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality.”

Viewable on the preprint server medRxiv, the study is currently under peer review, which allows experts to evaluate the methods and findings of other researchers.

The University of Chicago’s research arrived at the conclusion using a difference-in-differences analysis method, which compares the changes in outcomes over time between areas with low and high vaccination rates.

The estimate of 118 unnecessary deaths over 11 weeks between late March and mid-June 2021 makes a number of assumptions: Controlling for all other factors, including comorbidities, and treating vaccination rates as the same in these two different groups.

When examining ZIP codes, it’s clear that specific neighborhoods bore the brunt of the pandemic, including those in the Little Village, Brighton Park, Austin and West Garfield Park neighborhoods.

The study’s findings align with Chicago vaccine supply data, which was obtained through a public records request by the Documenting COVID-19 project, MuckRock and WBEZ.

The data shows that, of the 738 locations where vaccines were shipped in Chicago between Jan. 1 and Sept. 20, the communities that received the most doses of vaccine in 2021 were largely North Side and Near West Side neighborhoods — Lakeview, Logan Square and Lincoln Square. The Near West Side received at least 510,500 doses and at least 322,700 doses have been sent to the Back of the Yards community.

West Englewood, a neighborhood that received very few vaccine shipments in the initial months of the vaccine rollout, has since been able to administer more than 70,000 doses, ranking the neighborhood 15th in comparison to 75 other communities accounted for in city data.

Arwady noted that the city made extra doses available to residents of the 15 communities identified as highest risk based on its COVID-19 Community Vulnerability Index. The index ranked all 77 Chicago community areas based on four factors, including sociodemographic, epidemiological and occupational risk factors, as well the number of cases, hospitalizations and deaths occurring in those communities in the first year of the pandemic.

Of the 24 Chicago communities recognized as highly vulnerable , only the top 15 were included in the Protect Chicago Plus, a city initiative designed to saturate communities most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic with vaccine during late winter and early spring of this year.

Auburn Gresham, for example, was deemed “high risk,” ranking 23rd on the city’s vulnerability index. But it wasn’t high enough to be included in Protect Chicago Plus. Since late March, Auburn Gresham has seen one of the highest per-capita COVID mortality rates in Chicago, according to an analysis of Cook County Medical Examiner data compiled by South Side Weekly.

By summertime, canvassing teams fanned out block by block to get the word out in the neighborhood and to administer vaccinations in homes as needed. Today, Auburn Gresham’s vaccination rate stands at 51%.

“Different strategies and needs”

Parker’s study shows a grouping of under-vaccinated ZIP codes that led to a sizable increase in deaths during the spring wave. That’s despite the fact that Illinois has a higher vaccination rate than the national average, with 71% of residents 12 or older fully vaccinated, according to the Illinois Department of Public Health.

Previously hard-hit areas on the city’s South and West sides that were under-vaccinated as of January and February became even more susceptible to greater numbers of deaths when the fourth wave hit in March and April, Parker said.

For example, the total number of doses administered in Auburn Gresham hovered around just 1,388, among the lowest in Chicago, according to Chicago Department of Public Health records through Sept. 29.

Existing issues with access to general medical care and COVID-19 testing availability early on in the pandemic continued to play a role in vaccination rates in some areas of the county.

“The characteristics of places are still the same,” said Dr. Clyde Yancy, chief of cardiology at Northwestern. “We still see areas where public transportation is limited, less well-resourced schools, where housing is challenged. … We’ve got a lot of social engineering that needs to happen.”

During the first phase of the vaccine rollout that started in December of 2020, when demand vastly exceeded supply, shots were being sent to the hospitals that were prepared to use all of their inventory every week.

But poorly-vaccinated areas remained stagnant in part because the South and West sides house fewer hospitals that could provide vaccine clinics.

In the third wave, from March 28 to June 13 of this year, all areas of the city saw a spike in COVID-19 cases and deaths, though the highly vaccinated areas were the most well-off. The fourth wave, driven by the onset of the delta variant this summer, did not significantly impact the most vaccinated groups of the city, Parker said, but the rise in cases and deaths in poorly-vaccinated areas, according to the research, were vaccine-preventable deaths had the city’s vaccine distribution been more intentional and equitable.

For the city’s part, Arwady said public health officials distributed doses as widely and equitably as possible when supplies were tight. Where vaccination rates plateaued, the city shifted tactics to reach out to those hesitant to get the shot.

“There are different strategies and needs based on points in time that we tried to do based on data,” she said. “I would not do it any differently.”

How we analyzed the data

The University of Chicago researchers analyzed public data from the Chicago Department of Public Health to better understand the relationship between vaccination rates in specific ZIP codes within the city and related COVID-19 death rates. To compare vaccine distribution and spring wave deaths at the ZIP code level, the researchers mapped full vaccinations since March 28, 2021, and deaths per 100,000 residents during the spring wave.

The Documenting COVID-19 project and WBEZ obtained vaccine shipment data through an Illinois Freedom of Information Act request to identify the trends in vaccine supply and availability by community. We then mapped each vaccine provider to their underlying community area to estimate per-capita vaccine availability in areas with a high vulnerability index, or CCVI.

We compiled data on Chicago community areas from the city’s Community COVID-19 Vulnerability Index , which includes various public health metrics, and the Protect Chicago 77 website, which lists vaccination rates by community area. We derived community area-level mortality data from South Side Weekly’s tracker of Cook County Medical Examiner data, COVID-19 Deaths in Chicago’s Neighborhoods.

Matt Kiefer contributed to this report.

Kyra Senese is a Chicago-based freelance reporter and worked with the Brown Institute for Media Innovation’s Documenting COVID-19 project from 2020 to 2021. Follow @Kyra_Senese.

Smarth Gupta is a data research fellow at the Brown Institute for Media Innovation’s Documenting COVID-19 project and a graduate student at Columbia University. Follow @smarthgupta__.

Header image by BaLL LunLa via Shutterstock.