The Documenting COVID-19 project’s recent investigation with the Las Vegas Review-Journal unearthed important public health data, collected internally by the Southern Nevada Health District but not posted publicly, on so-called breakthrough infections of COVID-19 in fully-vaccinated Americans. The data showed more than 500 casino workers and 400 food-service workers, on top of 575 healthcare workers, in Las Vegas have contracted breakthrough COVID-19 cases.

Understanding breakthrough cases — what they do and don’t mean — is critical to keeping communities safe right now and developing public policy for the next stage of the pandemic, experts say. Better data on breakthrough cases could give researchers more information to study new variants of COVID-19 or help policy makers understand who should be prioritized for booster shots first.

But in May, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stopped tracking most breakthrough infections. Instead, the agency began reporting these cases only when they ended in hospitalization or death.

With no additional national reporting requirement on breakthrough cases, the country faces an all-too-familiar pandemic-era problem: states are left to figure out what data, if any, they collect about a growing public-health issue. In turn, health experts say we’re missing important information we need to answer critical questions at the next stage of the pandemic.

We think that the incomplete breakthrough case data across the country is again a chance for journalists, citizen-sleuths and anyone else to find the data they need and public health departments have. We put this tipsheet together to help you hold health departments accountable on providing COVID-19 breakthrough data.

Why you and your readers should care

- Sequencing genomes of strains for variants: With more breakthrough data, researchers can monitor for the emergence of new variants —specifically, variants that might be able to “escape” the immunity built up by vaccination.

- Disparate impacts on vulnerable populations: Little is known about how the protection that the three COVID-19 vaccines approved in the U.S. changes based on race or ethnicity, especially when driven by comorbidities or inequities in housing and workplaces. Having access to demographic-level breakthrough data would be the first step to address those inequities.

- Boosters and waning vaccine efficacy:Who should get booster shots first? Breakthrough case data could tell us if populations that got that vaccine early on or populations that work or live in high-COVID-risk environments should be first in line for boosters.

A quick note on framing

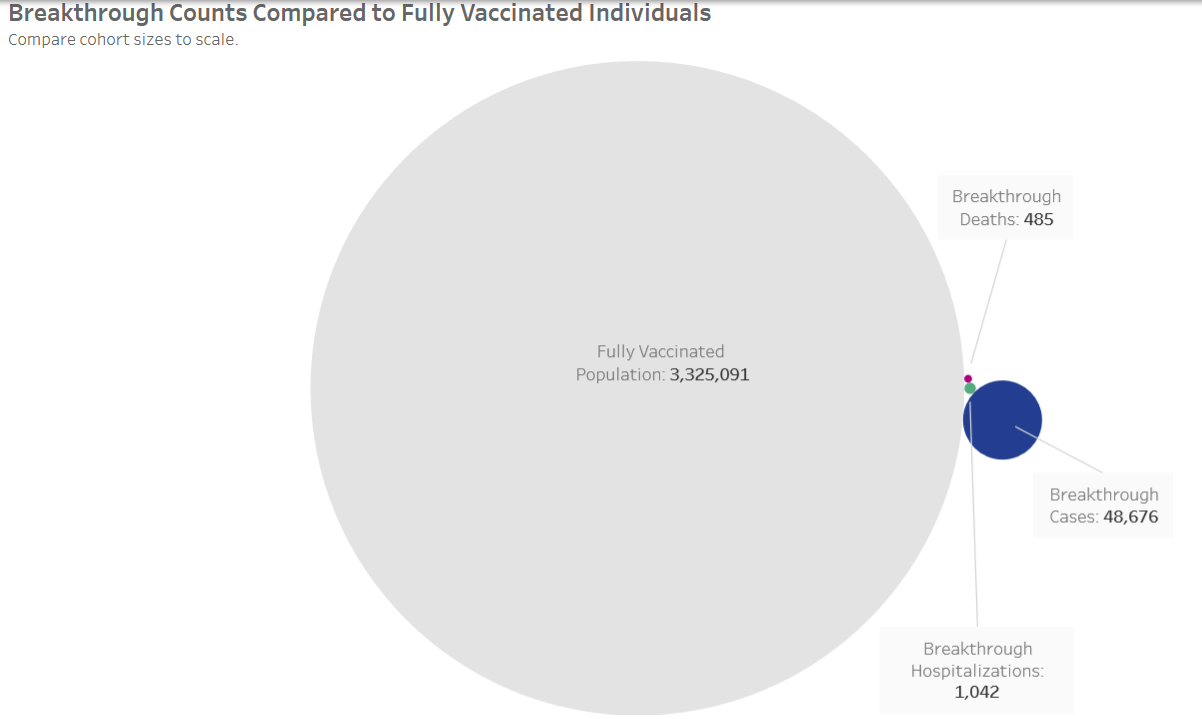

It’s always worth reminding yourself and your readers that breakthrough cases happen in a very small percentage of the vaccinated population. If you’re a journalist, make sure that the headline reflects that. My Documenting COVID-19 project colleague, Betsy Ladyzhets, explains “how to talk about breakthrough cases” excellently here. Mentioned in Ladyzhets’ blog post is an article from ProPublica’s Caroline Chen with a stellar headline: A Tiny Number of People Will Be Hospitalized Despite Being Vaccinated. We Have to Learn Why.

A graphic from Indiana’s COVID dashboard (which by the way, is a state that serves as an example of more robust breakthrough case reporting), says it all.

So… can we talk breakthrough data now?

Another note on framing

The word “breakthrough” itself is complicated. Dr. Oni Blackstock, a primary care and HIV physician, researcher and founder of Health Justice, believes that “breakthrough” is a word that is often misinterpreted when these cases are understood not as expected outcomes, but as anomalies.

“We know that no vaccine is 100% effective,” Blackstock says, “I think the word ‘breakthrough’ gives people the sense that getting an infection after being vaccinated is an inherent issue with a vaccine, versus the fact that this is how they’re designed.”

In other words, breakthrough cases are part of how vaccines work and not sudden deviations. Curb unrealistic expectations for the level of protection each of the three vaccines offer and take the time to read articles like this one by STAT News’ Helen Branswell, that has been continually updated to track vaccine efficacy.

Without further ado — the data

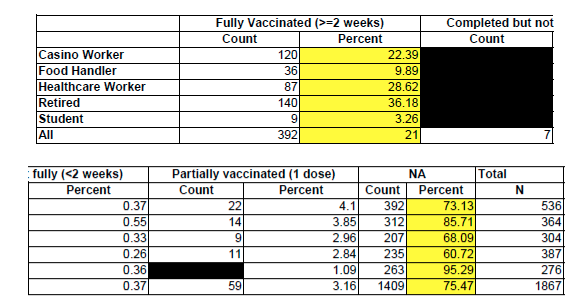

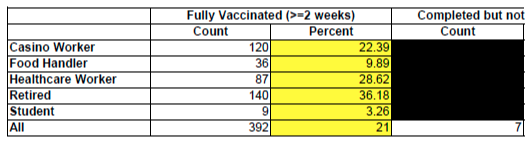

The Southern Nevada Health District included these two tables in a response to our request for emails from their top researchers that included the word “breakthrough.” The tables were buried in an email thread.

To help us get a better understanding of what we were actually looking at, I asked a representative from the district to answer a few questions about the data. My two questions:

- How is the data collected?

- And how are the categories for each occupation defined?

In response, the health district explained that it did not gather occupational information to actively investigate breakthrough cases, but instead, researchers compiled the data after-the-fact from recent CDC case report forms.

This is important because it means that the categories were limited to a few fields on the form and one field for contact tracers to enter a person’s self-reported job title. The fields on the form were healthcare worker, food handler and casino worker. From the self-reported field, researchers from the health district used a soundex matching algorithm to extract entries similar to “student” and “retired.” All other answers were lumped into a large “Other” category.

The variation in self-reporting on these forms makes the full implications of the data uncertain. On the other hand, there are always limitations and caveats in data journalism. So we decided it was worth publishing and reporting on this data as long as we were completely transparent about its limitations.

The take-away: Make sure you know who collected your data, how they collected it, and what their original purpose for the data was. The answer to those questions will go a long way.

So what breakthrough data does your state report?

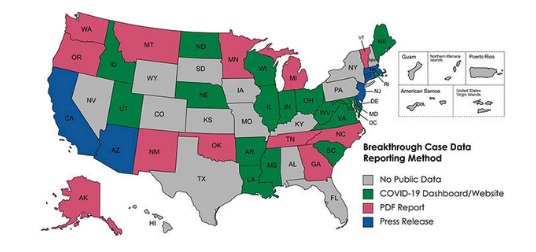

According to a report from Johns Hopkins in August, 15 states report no data on breakthrough cases and the reporting methods of the other 35 are “far from consistent and do not all contain the necessary level of detail.”

See the full details on Johns Hopkins site.

Even fewer states and health departments report a high level of detail on breakthrough cases, but a couple good examples are the Clark County Health Department and the Washington State Department of Health.

Also check out this report from July that should help in understanding how your state tracks and reports breakthrough cases.

Getting the Data

- Ask first: Does someone at your local state or health department know what data on breakthrough cases is being kept internally? Has anyone inside the department been interested in gathering this data, or analyzing the data by specific demographics? They may be happy to tell if any report has been done and who was involved in that report.

- Request the data: If you’re told that there is data but you’ll have to request it, try language like this:

Any available data on the number of breakthrough COVID-19 cases reported to the

INSERT HEALTH DEPARTMENT NAMEby race and ethnicity, age, sex, occupation and employer, by date and cumulative.If this data exists only in part, or needs to be segregated before release, please contact us directly.. We are open to negotiating on the scale and scope of this data request.

- Request the chatter: If you’re not given helpful information from the department about what information is or isn’t being kept, try requesting emails about breakthrough cases from your health departments top researchers using language like this:

All email correspondence, and all underlying documentation contained herein, between August 1, 2021, and the date that this request is ultimately fulfilled, sent to, from or copied to

INSERT HEALTH DEPARTMENT EPIDEMIOLOGISTS AND/OR RESEARCHERS’ NAMEScontaining the following non-case-sensitive-key-string: ‘breakthrough’.

In response to a request similar to the one above, we received the tables from above attached to a series of emails.

Remember this table?

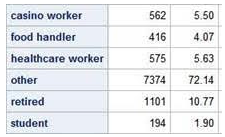

- Ask again: When we requested an update to the data that we received above, we got this table back:

It looks a lot different than the first one, right?

Again, make sure you leave time to ask the department about when the data was collected, what methods they used, and what purpose they imagined for the data when gathering.

The answers to these questions will be the “backgrounding” of that data, and all that’s left will be for you to do the interviews. Interview the data to find out what it is telling you, and then interview experts and impacted groups to see what it means to them.

Header Image: Kynetta Shinard, left of Mississippi checks in at the front desk of the Strat on Feb. 15, 2021 in Las Vegas. The desk clerk provided only her first name of Susan. Photo by L.E. Baskow for the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

This reporting recipe was produced by Dillon Bergin of the Brown Institute for Media Innovation and MuckRock’s Documenting COVID-19 project. Contact Dillon Bergin at dillon@muckrock.com. Follow @DillonBergin on Twitter.