Since early 2020, New York City has become a pioneer of wastewater surveillance, a method of tracking diseases in sewage that gained prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic. But city agencies are not being transparent about what they’re finding in our waste or how the data is used to inform public health decisions, according to a monthslong reporting collaboration between Gothamist and MuckRock.

According to interviews with current and former employees and city council hearings, workers running the wastewater program struggled during the first year of the pandemic to access the resources they needed to test sewage samples from the city’s 14 treatment plants — the largest municipal water network in the country. Meanwhile, the health department lacked capacity to develop analysis and communications strategies for this newer type of public health data.

Wastewater data are now publicly posted and the testing program has resources to continue into 2023, but the results remain difficult to see due to limited public visibility. Unlike other large cities with similar programs, such as Boston, New York City lacks a public dashboard where residents can find real-time updates of the coronavirus spread in their communities. New York City’s data does appear on individual web feeds run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and New York State, but the data is shared with a delay and is often weeks old.

“If it weren’t for a pandemic, this program could’ve taken five to 10 years to set up,” said Pamela Elardo, former deputy commissioner of the Department of Environmental Protection and past leader of the COVID-19 wastewater testing initiative. According to interviews and documents, the department scrambled to start monitoring sewers for COVID-19 in spring 2020, successfully establishing a process for testing samples by the end of the summer.

Separately, the New York City health department has provided few details on how wastewater data factors into COVID-19 decision-making. In statements this year, Health Commissioner Dr. Ashwin Vasan has described wastewater surveillance as another mode of keeping tabs on the pandemic as fewer and fewer people visit clinics for official testing.

When asked how the city is currently using this surveillance to inform policies, however, the departments of health and environmental protection said that they still consider wastewater-based epidemiology a “developing field.” The agencies said they are working on best practices for interpreting the data – even as this program approaches its fourth year of sampling the city’s sewers, according to a joint statement provided by health department spokesperson Patrick Gallahue.

This data is “becoming the first line to figure out what’s going on in a community” as fewer people get swabbed for COVID-19, said Amy Kirby, program leader of the CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System. Such information is particularly important during the holiday season and heading into 2023, she said.

At Columbia University in uptown Manhattan, an independent program has been a crucial source of information driving safety measures for the university’s 9,700 undergraduate students, serving as a smaller-scale example of how wastewater can be used to inform policy. Coronavirus detections in sewage coming from specific residence halls have triggered alerts instructing students living there to seek out PCR testing.

A bill introduced to the New York City Council in August would make the wastewater surveillance program permanent, expand it to other public health threats as needed, and require the health department to report data on a public dashboard. A public hearing has not yet been scheduled for this bill, but it’s on the docket for the coming months, said City Councilmember Keith Powers, council majority leader and the legislation’s chief sponsor.

While the testing program – which has cost more than $1 million over nearly three years – can continue as a pilot into 2023, the City Council bill would give municipal agencies resources to expand the program and a mandate to integrate wastewater into routine health surveillance, Powers said.

Programs without such a mandate “can often fall to the wayside when it’s time to start looking to cut budgets,” he said.

“Everyone wanted our wastewater”

Soon after COVID-19 became a global public health threat, environmental science researchers realized that it could be tracked in sewage: the novel coronavirus abundantly showed up in patients’ waste. As the U.S. faced a dearth of tests, monitoring that sludge on a broad scale presented a more efficient way to track the virus’ spread at the community level. A small number of people might have access to a PCR test, but everyone poops.

New York City, as an early epicenter, quickly drew the attention of researchers hoping to test this technique. Elardo recalled that “multitudes of academics,” as well as private sector researchers, wanted access to the city’s sewers.

Instead of taking these offers, spokespeople stated the city’s Department of Environmental Protection chose to set up a program in-house, while collaborating with academic researchers to develop its wastewater screening process. This choice provided the agency with more control over testing and analysis methods, as well as ownership of the eventual data. Any publication would go through the city’s environmental and health departments, ensuring that it was communicated responsibly, Elardo said.

“DEP carefully considered the offers it received,” said health department spokesperson Patrick Gallahue in a joint statement with the environmental protection agency. As researchers were still early in determining how to test wastewater and use the resulting information, the agency decided to build on existing partnerships with local academic teams rather than taking on new collaborators.

Like other wastewater networks, New York City’s 14 treatment plants are routinely monitored to ensure they meet regulatory standards. But testing for a virus was entirely new territory for DEP.

Collecting waste, isolating viral material from those specimens, and examining the genetic patterns took significant time and resources. Because the virus naturally mutates over time, scientists can use those genetic changes to track how the germ moves through a population — similar to how genealogy can explain historic migrations of human communities.

But this research is highly specialized. DEP staff started monitoring for COVID-19 with the limited analytical equipment they had in spring 2020, Elardo said. New York City even received permission from the state department of environmental conservation to cut down on other routine, regulatory waste evaluations, so that staff could devote more time to the COVID-19 project.

DEP requested funding to buy new analysis equipment and hire staff, but approval from the Office of Management and Budget took months. Elardo and her colleagues “had to push” the city to receive the funding they needed, recalled Councilmember Gale Brewer. Brewer, who also served as Manhattan Borough President early in the pandemic, initially helped advocate for the wastewater testing program.

Even when the funding was approved, lab equipment faced shipping delays and did not arrive until the end of 2020, according to a city council hearing in October of that year. Accessing needed supplies and equipment was “a challenge that virtually all entities had due to supply chain issues,” DEP and health spokespeople said.

Then-Councilmember Costa Constantinides, chair of the Committee on Environmental Protection, introduced a bill to create a pilot program for wastewater testing in June 2020. This bill granted DEP additional resources and required the department to produce a public report about its efforts.

But the legislation didn’t take effect until March 2021, almost a year after DEP had already begun its surveillance efforts.

Making the data public

By late 2020, scientific research had demonstrated that COVID-19 trends in sludge could predict the rise and fall of a surge, corresponding with more traditional PCR test results and providing a potential early warning system.

But New Yorkers had no access to this data for their city. Speaking to the City Council in October 2020, then-DEP Commissioner Vincent Sapienza said that the health department was “early on” in figuring out how to use wastewater data for public health decision making.

“How we would put [the data] in a format that’s useful to anybody other than the health department seems to be a challenge,” Commissioner Sapienza said, when asked about DEP’s plans to publicly publish wastewater testing results. Councilmember Constantinides pointed out that models for such publication already existed, from cities like Boston – which has collaborated with surveillance powerhouse Biobot Analytics since early in the pandemic.

Though scientists have tracked diseases through wastewater since the 1940s, this technology expanded to a much broader scale for tracking COVID-19. City agency spokespeople said they “held off on publishing results until they could make full use of the updated guidance issued by the CDC.”

Boston’s wastewater dashboard was first published in summer 2020. New York City did not publicly post any of its data until a year and a half later in January 2022. That’s when DEP began sharing results on the NYC OpenData portal. A month later, New York City data also became available on the CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS) dashboard. For its participation in this national program, DEP sends copies of its sewage samples to a contractor hired by the CDC that analyzes them along with submissions from hundreds of facilities and jurisdictions across the country.

This CDC arrangement is intended to jumpstart wastewater testing at state and local health departments that lack resources for an in-house program, NWSS director Kirby said. New York City chose to use the CDC contractor even though it already had its own operation, creating two parallel datasets that can be compared for similar trends. Participation in the CDC program also helps the national agency access samples from the city for research, such as its study of this year’s polio outbreak.

Even now, New York City’s wastewater findings — both on the CDC’s dashboard and the city’s OpenData portal — are reported with significant lags. On Dec. 14, for example, the most recent data points available on the CDC website were from Dec. 5, more than a week earlier. Meanwhile, the city’s OpenData portal only updates wastewater results once a month. These delays render the information less useful to New Yorkers looking for an advanced warning about COVID-19 patterns.

Relying on the CDC dashboard can lead to other challenges. In April, data for hundreds of the CDC’s monitored sites suddenly became unavailable when the federal agency switched contractors. Kirby said it took time for the new company, Biobot, to coordinate with all the contract sites.

As a result, the contractor switch led to a lack of New York City data on the national portal for months during the city’s spring surge, at a time when PCR testing was decreasing and public health information was sorely needed. Other communities across the country similarly lost access to public wastewater data during this time.

NWSS chose to take locations like New York City off its dashboard “to indicate it’s a clean break between one contract and another,” Kirby said. But she acknowledged that the lack of data “caused some concern.” Kirby and her colleagues are working to ensure future changes in wastewater sampling logistics – such as the end of Biobot’s contract in January – do not cause more gaps.

As of this fall, New York City wastewater numbers are additionally available on a statewide dashboard run by researchers at Syracuse University, the State University of New York and state agencies. But the city data tend to be more delayed than data from sites in all other New York counties, said Dr. David Larsen, a Syracuse University professor who runs the dashboard.

“New York City sends us data on a weekly basis,” Larsen said. “Depending on when the test is done, there’s a built-in lag there.” For other New York counties, which are tested directly by the research consortium, data are available on the dashboard within 48 hours of sample collection.

In response to the data delays, DEP and health spokespeople pointed out that individual wastewater results “do not generally provide a complete picture” of how COVID-19 is spreading. They also said, unlike in other parts of the country, trends in city wastewater data tend to align with case counts rather than predicting them.

“New Yorkers who want advanced warning about COVID-19 patterns should follow our reported case counts, data which is publicly and readily available,” the spokespeople said. This emphasis on case data counters both previous statements from city officials and insights from public health experts.

Official case data has “become less dependable” in the last year thanks to the rise of at-home tests and other factors, Mariana Matus, CEO and co-founder of Biobot, said via email. “This is why hundreds of cities around the country make wastewater data available to the public and use it as an early warning signal to prepare for the emergence of future variants and outbreaks,” she added.

In 2022, wastewater showed a higher level of COVID-19 spread than PCR testing, as the latter became less available, according to Gothamist and MuckRock analyses. This pattern suggests that the sewage numbers may more accurately reflect actual disease patterns.

If the health department ran its own dashboard, it could deliver data more frequently and better tailor updates to New Yorkers’ information needs, said Colleen Naughton, an environmental professor at the University of California, Merced, who leads wastewater testing for California’s Central Valley region.

A dashboard showcasing data from the Merced program – available in both English and Spanish – was designed based on “feedback directly from the community,” Naughton said, aiming to answer pressing local questions. Her team also delivers data in a weekly email update for local health officials and other community members, as well as weekly explainer threads on Twitter.

How the sludge gets scanned at Columbia

New York City’s wastewater surveillance program provides information from 8.6 million city residents, and each treatment plant represents poo and pee from hundreds of thousands of people. At Columbia University’s Morningside Heights campus, the surveillance is more concentrated, given a team of researchers captures the sludge from individual undergraduate dorms.

The sewage surveillance – which started in fall 2020 – has proven especially important after the university ended its mandatory PCR testing program, said Melanie Bernitz, vice president of Columbia’s in-house health care program and a member of the university’s COVID-19 task force.

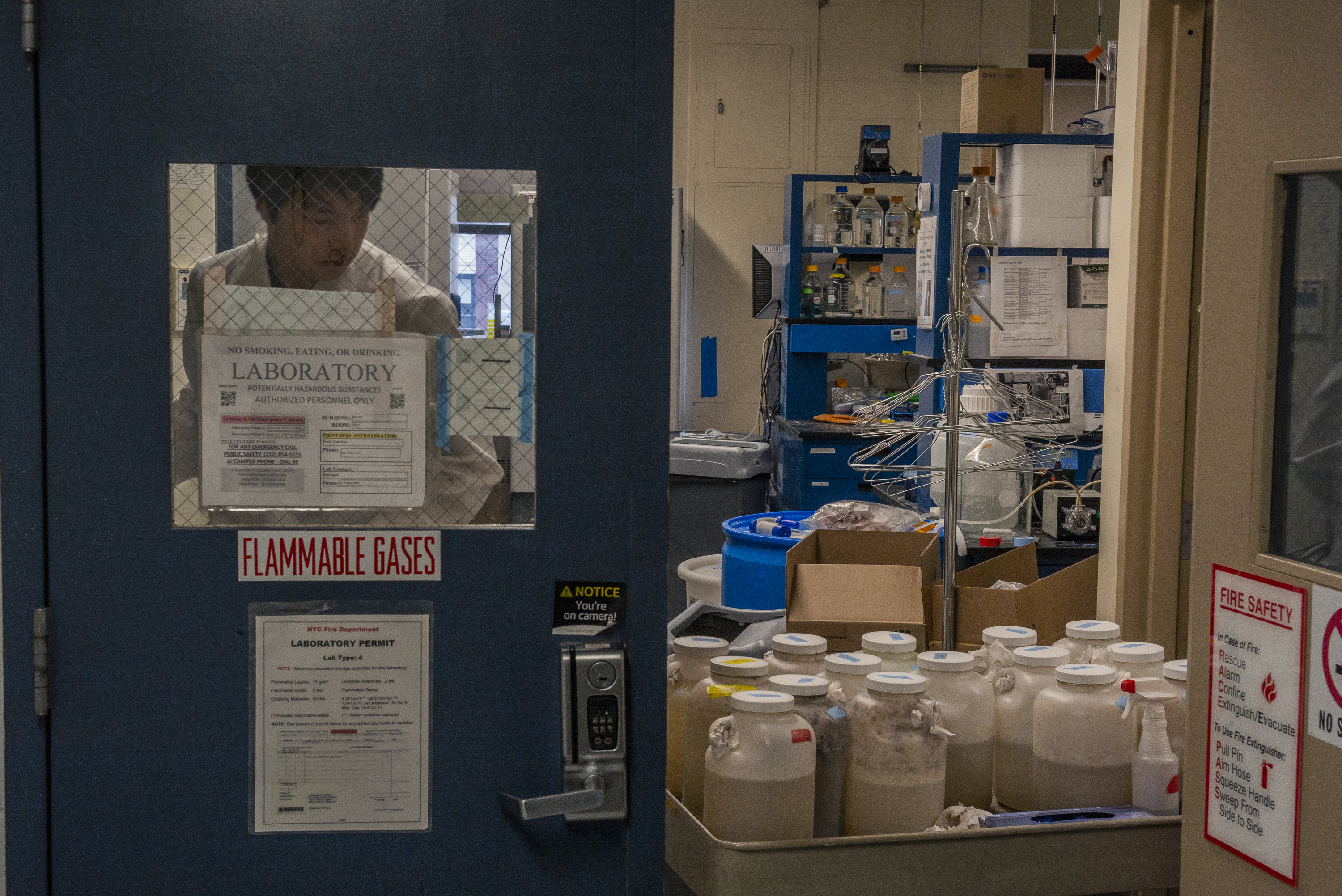

Every Monday, Wednesday and Friday morning, an environmental engineering student from professor Kartik Chandran’s lab makes the rounds to 20 undergraduate dorms. At each dorm, the student heads down to the basement and collects a gallon jug hooked into the building’s wastewater system. These jugs are programmed with a machine called an autosampler, which takes in a small amount of water once an hour for 24 hours.

The dorm testing “covers more than 95%” of undergraduate students, said Chenghua Long, a PhD student in Chandran’s lab who manages the program. Students who choose to live outside the residence halls are not included.

Long shares collection duty with several other graduate and undergraduate students. The process takes about two hours, followed by an afternoon of prepping the waste for testing at Chandran’s lab in the engineering building. Each sample must be transferred into smaller bottles and put through a centrifuge to separate out solid and liquid waste. It’s then filtered to isolate any coronavirus material that’s present, and finally tested with a PCR machine. Samples collected at 9 AM are usually translated into results by the end of the work day.

Like the DEP lab, the Columbia researchers spent a lot of resources setting up their wastewater program, Chandran said. That included the “intellectual resources” required to design the testing process — which pulled Long off of his previous PhD project – and new equipment to speed up the analysis.

Once a month, the team also screens wastewater samples for coronavirus variants, testing the samples from Columbia as well as those from the North River water treatment plant in upper Manhattan and a sewershed in Bergen County, New Jersey. This side project provides a more comprehensive picture of coronavirus strains on campus and in New York City than what researchers would get with clinical testing and has flagged “cryptic” mutants unseen elsewhere that may be highly contagious.

“I would like to be able to do it at least once a week,” Chandran said of the variant testing, but that would be more resource-intensive. The city health department is similarly testing sewershed samples for variants. Data from this program is available on a CDC dashboard, but is typically delayed by at least a week.

In 2022, PCR testing is no longer mandatory and students are “back to partying in each other’s dorms,” Bernitz said. Administrators now use the wastewater data for a more campus-wide perspective on transmission, and they still send out alerts to encourage students to get a PCR or rapid test if a dorm’s sewage suggests an outbreak.

“If we were to see something very concerning, we could consider changing policies,” such as bringing back a mask mandate, Bernitz said.

Columbia administrators have much more power to enact public health measures over tuition-paying students than the New York City health department has over the average resident. But some lessons from the university still apply to larger-scale systems, Bernitz said. She recommended “public-facing websites” and alerts tailored to residents’ ZIP codes, flagging coronavirus increases in wastewater and suggesting people get tested.

“Public messaging that includes wastewater data” tends to “get more attention” than other COVID-19 alerts, Kirby said, based on anecdotes from agencies working with the CDC’s national program.

New York City’s health department could additionally work with Health + Hospitals to send mobile testing sites or healthcare resources to sewersheds where wastewater levels indicate outbreaks, Kirby and other experts recommended.Other health departments are using this data as an advanced warning for hospitals, Kirby said, A wastewater increase could be a sign that medical centers will “soon be seeing increases in their emergency department visits.”

Spokespeople from the health department and DEP said that wastewater provides “questionable” utility, given that city sewersheds include such large populations, some more than one million residents. The agencies have previously tested for COVID-19 at individual manhole sites and sewage pumping stations to get better resolution, but this process is resource-intensive and currently not occurring at a broad scale.

Future of NYC’s testing program

Experts who work on wastewater surveillance share a desire for their results to be broadly communicated, but people are often unaware that their waste is serving a public health duty. One recent study from researchers in Louisville, Kentucky found that less than half of residents surveyed knew that the coronavirus could be detected in sewers, and less than one-third were aware of a local monitoring program run by the University of Louisville.

“The value of a surveillance system for infectious disease surveillance is simply to improve understanding of what’s going on,” Larsen said. Ideally, public communication should allow anyone from individuals to elected officials to make decisions about safety precautions.

Sharing wastewater data should go beyond online dashboards, recommended Naughton from the University of California, Merced. She would like to see public alerts, including information translated to other languages. Health departments should use “radio, infographics, and other ways to reach people that might not be looking on Twitter,” she said. Kirby compared wastewater updates to a weather report, the type of brief update that might be delivered on WNYC each morning.

But a local dashboard would be a helpful starting point, and the New York City Council bill introduced in August would make this reporting permanent. The DEP and health department declined to comment on the bill, though noted that they anticipate continued participation in the CDC’s national program in 2023.

The next step for the bill is a public hearing, which has yet to be scheduled as of mid-November. The City Council has “a lot on the table right now,” Councilmember Brewer said, but she has not heard of any opposition to the legislation. The 2021 bill to establish the pilot program passed without a single “No” vote.

For Brewer, the top priorities for the wastewater program are to continue it, maintain sufficient staff and machinery for the lab and publish real-time data. “If you don’t keep it up, and you don’t make it real-time and you don’t make it transparent, then people will not be using it,” she said.

New York City waste is also undergoing testing for monkeypox and polio through partnerships with the CDC and New York State agencies, but those data aren’t public beyond occasional press releases.

With a permanent program, the city agencies could also expand their sludge surveillance to other threats, ranging from the flu and RSV to antibiotic-resistant bacteria, a public health problem that intensified during the pandemic.