The FBI spent five years searching for Orhan Gündüz’s killers, focusing on two men who had attempted to bomb a Turkish consulate in Philadelphia the same year, 1982. This is the final piece in the Kapikill Files series — read chapter 1, chapter 2 and chapter 3.

The Kapikill files reveal that a year after Orhan Gündüz’s killing, the FBI had narrowed its list of suspects to the five “Fauxbom“ defendants who attempted to bomb the Philadelphia Turkish consulate in 1982. Of these five young men — Karnig Sarkissian, Viken Yacoubian, Viken Hovsepian, Dikran Berberian and Steven Dadaian — Bureau agents would focus on two, ultimately confronting these suspects in simultaneous interviews on the same day, according to the redacted documents.

But after a five-year investigation with numerous leads, ensuring the safety of a source who identified Orhan’s killer took precedence over bringing charges.

In the four decades since his role in the Fauxbom plot and allegedly bragging about being in Boston when “something happened to the Turks,” Sarkissian’s powerful voice and earnest songs of the homeland kept him a beloved figure in the Armenian diaspora. Judge Bruce D. Albertson asked for details of the conviction at the hearing.

“He was charged as part of a conspiracy to bomb a building in Philadelphia, I believe. One person was captured at an airport,” Assistant Commonwealth’s Attorney Michael Kopp said. “The crime was from 40 years ago,” he added.

Sarkissian’s attorney, Aaron Cook, stepped in. “Judge, he is a singer, and he is Armenian, which factors into what happened in the 1980s. It involved Turkey.”

Both explanations, while accurate, downplay the FBI’s fear that the attack could have caused as many as 3,000 casualties and that it came as part of a campaign waged by the Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide (JCAG) that killed three Turkish diplomats on U.S. and Canadian soil in 1982.

This could be the last moment Sarkissian’s activities in 1982 are ever mentioned in a courtroom. The plea hearing also provided confirmation of an important biographical detail: his June 13, 1953 birthdate.

The FBI lists that birthdate as belonging to the suspected buyer of the Volkswagen Rabbit found near the scene of Orhan’s assassination with a pair of jogging pants that matched the jacket thrown away by the assailant.

From ‘Mr. Loosciano’ to the ‘singer’

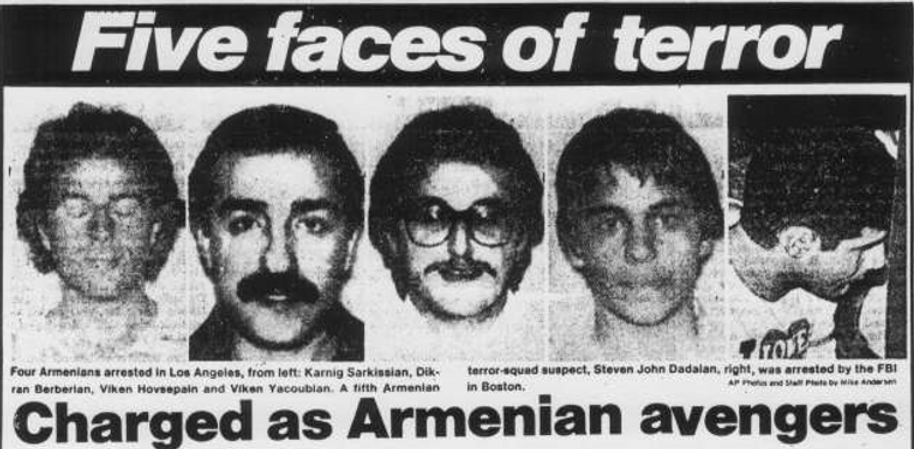

On Oct. 22, 1982, two days after the FBI arrested the five “Fauxbom” suspects who would become known as the “L.A. Five,” the Boston Herald ran a full page on the aftermath with the headline “Five Faces of Terror” and photos with their ages: Sarkissian, 29, of Anaheim; Hovsepian, 22, of Santa Monica; Berberian, 29, of Glendale, Dadaian, 20, of Canoga Park, and the youngest, Yacoubian, 19, of Glendale, who would have been only high school-aged during this peak of the alleged Justice Commandos (JCAG) activities. Below their photos ran an image of grief-stricken Meral Gündüz, still mourning the loss of her husband.

The five men were indicted on three counts of conspiring to bomb the consulate as well as possession and interstate transportation of explosives. Sarkissian, Yacoubian, Hovsepian and Dadaian would be tried together; Berberian was tried separately.

The FBI had already linked one of them to the man who gave the false name “Mr. Loosciano” when purchasing the Rabbit believed used in the Gündüz assassination. The same member of the Fauxbom suspects identified by the Rabbit’s owner was also linked to a description of a “singer” who had made records about the genocide, a celebrity even, picked out by a prison informant after they shared a conversation in jail about his possible involvement in assassinations in Boston and Australia. JCAG-claimed killings had included the 1980 assassination of Turkish Consul General Şarık Arıyak and his bodyguard Engin Sever in Sydney, Australia. In May 1982, an anonymous female with a “strong accent” had called the Australian Turkish Consulate shortly after the Gündüz assassination claiming to give the redacted identity of the “Boston shooter,” linking the two cities again.

The prison informant said the singer admitted to having two young sons, along with other personal details. Willing to submit to a polygraph, the informant had concerns about his own safety if he testified. He said that his fellow prisoner and his group of associates were “very dangerous.”

Of the five arrested in the Fauxbom case, one, in fact, was a famous singer born in Aleppo, Syria: Karnig Sarkissian, a “good” one at that, an FBI memo stated.

The FBI continued its investigation into links between the Fauxbom defendants, who awaited trial for the bombing attempt, and the investigation into Orhan’s murder. Multiple unredacted references within the files also list the birthplace of one of the suspects as Aleppo, Syria, while also noting that the prison informant recalled the Fauxbom defendant mentioning his childhood in Syria. Agents also continued their trace on the weapons found at the Somerville crime scene and their investigation of a gun dealer who they believed had been involved in the sale of one of the murder weapons.

As subpoenas for grand jury testimony were issued after the Fauxbom arrests in late 1982, agents determined the gun dealer would not be a reliable witness after finding inconsistencies in interviews that appeared to be an effort to protect him — the Bureau even contemplated perjury charges.

A year later, as another possible grand jury loomed in October 1983, the FBI’s Los Angeles office insisted that the Bureau should protect a source that had been instrumental in stopping the Fauxbom plot by not using their positive ID of Orhan’s killer, noting, “FBILA is of the opinion that if this information was used for grand jury proceedings and subsequent arrest warrant for [redacted] the identity of [redacted] could not be fully protected.”

‘We don’t want to sound paranoid’

Around the time that the attempt at an indictment fell apart, it had been more than a year since JCAG had struck within North America. On Oct. 29, 1983, three months after the group claimed responsibility for the assassination of Dursun Aksoy, administrative attaché of the Turkish embassy in Belgium, a hunter in Franklin, Massachusetts discovered a cache of 125 sticks of dynamite in the woods next to a youth camp owned by the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF).

The FBI previously explored an AYF camp in California as a potential recruiting ground for JCAG members when it arrested AYF member Hampig Sassounian for the killing of Turkish Consul Kemal Arikan.

The FBI determined that the explosives found in Franklin were the same manufacturer and model as the dynamite discovered in the Fauxbom plot. Further tracing found that the youth camp dynamite was from two shipments of dynamite—produced one day apart— that were stolen from an industrial site in Kalkaska, Michigan.

A suspect in the theft—apprehended in 1980 on narcotics charges—told Houston law enforcement he sold the stolen dynamite “to a group of Arab radicals from Dearborn, Michigan.”

FBI agents discovered no other evidence related to a rumor of the camp “being a training site for Armenian terrorists.” But an interview with someone involved at that camp, name redacted, did little to allay the concern: “What are a few dead Turks compared to two million slaughtered Armenians,” the interviewee said. “Terrorism has its place when conducted in the correct manner, witness the PLO.”

If anything, the witness concluded, JCAG had not gone far enough:

“We don’t want to sound paranoid, but where the police uncovered everything, there was so much wiring you could wire the whole camp,” the representative said. “We are concerned and somewhat justifiably frightened.”

While the article reported Armenian fears of a “Turk plot,” the evidence that the explosives were from the same stolen shipment as the dynamite recovered in the Fauxbom plot was missing from press reports.

As the L.A. Five’s legal proceedings continued, they received steady support from Armenian American groups across the country. Two names were singled out of the L.A. Five as featured guests at concert fundraisers: Sarkissian, 31, and Yacoubian, 21.

It wasn’t until the summer of 1984 that the trial of Sarkissian, Yacoubian, Hovsepian and Dadaian began in California, with Viken Yacoubian’s father testifying that the genocide “was his son’s driving obsession” while growing up in Beirut.

In October 1984, Judge Mariana R. Pfaelzer said she was “impressed by the defense arguments.” The judge convicted them for plotting to bomb the consulate, but stated that their testimony wasn’t given in vain and that she would “take it into account during sentencing.”

The assistant U.S. attorney warned that if left free in the interim, Yacoubian, Sarkissian, Hovsepian and Dadaian might commit another terrorist attack and asked that their $500,000 per-person bail be revoked. The judge denied the request, “chastising” the prosecutors. The fifth Fauxbom suspect, Berberian, still awaited trial.

The suspect: ‘If I talk to you, I’ll go to jail’

On Jan. 25, 1985, Judge Pfaelzer issued sentences for three of the convicted four Fauxbom defendants, leaving Yacoubian out.

“The case involves a really terrible tragedy,” she said, referring to the genocide. “I have no doubt the defendants are basically of good character and unlikely to repeat the acts. Nonetheless, it was methodically planned. It was not amateurish. I must incarcerate the defendants.”

Disagreeing with the government’s proposed sentences, Judge Pfaelzer sentenced them to federal prison camps in California. Viken Hovsepian— “accused ringleader of the group”— received six years; Karnig Sarkissian, five years; and Steven Dadaian, four years.

But the court granted the youngest, Viken Yacoubian, an evidentiary hearing for a possible new trial after his attorney convinced the judge that the government psychiatrist had not considered all available evidence in determining whether or not Yacoubian suffered from a mental disorder during the crime.

The fifth Fauxbom assailant, Berberian, had a separate trial after adopting a different defense strategy.

Meanwhile, the FBI moved forward with the Kapikill investigation and its theory that the assassin was one of the five Fauxbom defendants.

FBI files further reveal that the suspect they had in mind for the assassination was possibly a high school senior in 1982 and that the suspect matched two eye witnesses’ descriptions in Somerville.

Entering February 1985, the FBI planned the simultaneous interviews of two individuals— names redacted—including the “prime suspect” in Orhan’s murder, prior to a planned grand jury subpoena. They also noted that one of the individuals was “free on bond pending appeal” for Fauxbom.

On Valentine’s Day, Boston FBI case agents held a conference with assistant U.S. attorneys in Boston and Los Angeles and determined that they would not interview the two individuals at that juncture for fear that “both individuals would flee the country,” based on prior JCAG behavior. One of the assistant U.S. attorneys, however, “believed that an indictment for conspiracy in the assassination of Orhan Gündüz could be made” against one of the two individuals they planned to interview.

A memo states the hope of that indictment would be that the unnamed conspiracy suspect would “roll over” and furnish detailed information concerning the assassination, bringing the FBI closer to arresting the suspected shooter.

That assistant U.S. attorney also recommended that they obtain records under a sealed search warrant from Rose and Alex Pilibos Armenian School for the student records, specifically looking at 1982 attendance information.

The FBI said it worked closely with a “highly sensitive, reliable vulnerable source,” referred to as “Source One,” who identified the assassin. Witnesses’ physical descriptions of the shooter further made Source One “confident” that they correctly identified the Boston assassin.

The FBI requested and received the Pilibos school records, but the information did not prove valuable because attendance was denoted cumulatively instead of day-to-day recording. The records could not show dates of absences and dates of enrollment during the period in question.

In the fall, believing the potential threat to a key source was lower, the FBI finally made plans to move forward with their original plans to locate and interview two suspected participants in Orhan’s murder on Oct. 2, 1985.

On a sunny, 75-degree Los Angeles day, FBI agents approached one of the two suspects they had linked to the murder of Orhan Gündüz through their multi-year, coast-to-coast investigation, in the parking lot of Printania Gifts, 1726 N. Vermont Ave., Los Angeles. The specific ties of the suspect to the store are redacted in the files. They questioned him about his participation in the assassination.

“I don’t know what to say right now. I’m confused. Would you give me a day to think about it?” the suspect told the interviewing agents. “If I talk to you, I’ll go to jail and if I don’t talk to you, I’ll still go to jail.”

On Oct. 4, he was interviewed again by agents in the presence of the assistant U.S. attorney, but declined further cooperation, stating, “if the U.S. government had the evidence that he assassinated Gündüz, it would have to be proven in court.”

Though he provided no further indication of his involvement, based on his behavior, the interviewing agents concluded that the suspect they confronted in the parking lot “did in fact assassinate Orhan Gündüz” and that he had been advised to not speak further by an outside source in between the two interviews.

Across town in Anaheim, FBI agents simultaneously made contact with the other suspect they had linked to the murder. They questioned him near “his [redacted] Crown Day Cleaners.”

The suspect denied any involvement and any evidence presented to him.

‘A code of silence’

The investigation slowed after the 1985 interviews. Attempts at matching the voice of a suspect to the tape of the caller to the UPI office on May 4, 1982 claiming the assassination for JCAG proved fruitless. A 1985 subpoena compelled a redacted Fauxbom suspect to read the statement into a recorder.

“After aural and spectrographic analysis … it was the opinion of the expert examiners that the suspect [redacted] did not make the questioned call,” a 1987 memo reads. “This opinion offered with a moderate level of confidence.”

The FBI hosted conferences in Los Angeles and Boston, in coordination with Canadian law enforcement, to review evidence in Kapikill and the Ottawa-based Atilla Altikat killing across FBI offices. In 1987, a memo lamented that a source who claimed to have trained the Boston gunmen would offer tips on any future assassinations but would not speak to any killing that had already occurred.

The memo is among the last in the released files:

After a long period with no leads, the most recent memo appears in 1993, noting that party leaders within the ARF were due to arrive at Dulles International Airport outside Washington, D.C. and continue on to Los Angeles for an interview “to further the solution to, and arrange the confession of, the perpetrators” of the Gündüz and Altikat assassinations.

Beyond the fact that neither claimed to know the identity of the assassins, the issue was not an unwillingness to reveal their identities but internal issues within ARF.

“It seemed [redacted] wished to test and be assured about the good faith and sincerity of the U.S. government, and to impart a sensitivity as to the political problem that a voluntary surrender and confession would present to the ARF leadership,” the memo states. “There was no statement that it could not be done or would not be done only the issue of how to implement it.”

Based on the file contents, no one ever confessed to the FBI and no charges in Orhan’s death were put forward.

‘I have killed a man. But I am not a murderer.’

While on trial as members of the L.A. Five, Yacoubian and Sarkissian’s counsel built their defense on the weight of intergenerational trauma of the Armenian genocide. It echoed the defense strategies employed during a trial from their grandparents’ era.

Soghomon Tehlrian told a jury that in 1915 that he woke up three days after Ottoman soldiers attacked his family, crawled from under his brother’s body and found his way home to recover a sack of gold coins. Tehlirian said his brother’s head had been split by an ax, and his sister was presumed dead along with his mother and father. Tehlirian would wander for six years, finding himself in Berlin by 1921.

Tehlirian found a room across the street from Talaat Pasha, former leader of the Ottoman government and convicted war criminal. Talaat was widely known as the man who ordered the extermination of Armenians. Tehlirian said at his trial that he knew him as the man who murdered his family.

Tehlirian, suffering from “seizures” likely caused by post-traumatic stress, recounted a dream where his dead mother’s corpse told him: “You saw Talaat and you did not avenge your mother’s, father’s brothers’ and sisters’ murders? You are no longer my son.”

Apprehended near Talaat’s body, Tehlrian said at trial: “I have killed a man, but I am not a murderer.”

Amid a few gentle questions about whether the murder was premeditated, the jury had been hooked, moved by Tehlirian’s attempt to avenge his family and an entire people. “They Simply Had to Let Him Go” the New York Times headline stated.

According to his son, who had changed his last name and spoke to columnist Robert Fisk anonymously in 2016, many of the details of Tehlirian’s testimony, published in English decades later by the ARF, were fabricated to protect a plot to avenge the genocide.

He traveled as far as Boston to plan Talaat’s killing as part of the ARF’s Operation Nemesis, where a team of assassins killed seven Ottoman leaders and Armenian “traitors,” including the man who helped create the list of 250 influential Armenians killed as part of the first wave of the genocide.

By the time the full scope of the plot emerged, he was free and lived as a hero among the Armenian diaspora. He died in 1960 in California.

His trial brought greater awareness of the Armenian genocide to newspapers across the globe while keeping the organized nature of Talaat’s killing hidden. In 1973, after the truth of Operation Nemesis was known, genocide survivor Gourgen Yanikian lured Turkish Consul General Mehmet Baydar and Consul Bahadır Demir to a hotel room in Santa Barbara, shot both and called the police. He hoped to trigger a trial akin to an “Armenian Nuremberg.” Sentenced to life in prison, his declining health helped earn him parole in 1984 before dying two months later at 89.

During the next decade, a small group of diasporan Armenians who heard stories of the genocide from their grandparents began applying this lethal blueprint to Turkish officials like Orhan Gündüz. Those same officials, born after the genocide occurred, had been raised to believe the violence against 1.5 million Armenians was itself a fabrication, despite the overwhelming historical evidence. The new generation’s crime— in the eyes of JCAG—was denial.

‘This is not just symbolic’

On April 24, 2021, hundreds gathered at the Boston Common’s Parkman Bandstand to commemorate Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day. It was almost exactly a century after Operation Nemesis.

The 2021 commemoration was also—for the first time—a celebration and a victory brought about by decades of nonviolent, political advocacy. That same morning, President Joseph Biden became the first sitting U.S. president to formally recognize the Armenian genocide, using the long-sought terminology despite warnings from NATO ally Turkey.

Participants recalled the bittersweet moment of the day’s victory. It took decades for most Armenian survivors to tell their stories, and longer for subsequent generations to find their advocacy platform. For survivors and their descendants, the collective trauma, loss and search for accountability became a unifying factor over generations of a global diaspora.

Speakers at the event cited the 10 stages of genocide — classification, civilization, discrimination, dehumanization, organization, preparation, with persecution, extermination and denial.

For 106 years, that final stage—denial—has been at the crux of tensions between Turks and Armenians. For decades, it was also the focus of the Armenian-American political platform in the U.S. The violent operations of the Justice Commandos and other Armenian terrorist groups became an obscure footnote for Armenian groups overwhelmingly focused on peaceful legislative advocacy for formal recognition.

While Boston Armenians marched in commemoration and celebration, attorney Mark Geragos stood in a pandemic-limited crowd of 40 in New York City’s Times Square. Known for representing celebrities, Geragos has litigated against insurance companies, seeking claims on behalf of descendants of policyholders who died in the genocide. In addition to representing a member of the L.A. Five, his father represented Hampig Sassounian during his trial for the killing of Turkish Consul Kemal Arikan, a crime which JCAG claimed as their own. Geragos took over Sassounian’s representation from his father decades later.

“We had been promised this as a community so many times, President Obama being the foremost example,” Geragos said after the 2021 anniversary, noting a campaign promise to use the word turned into waffling by April 24, 2009. Obama continued to use the term Medz Yeghern (“Great Calamity,” a term used by Armenian elders).

“This is not just symbolic,” Geragos added. Presidential recognition was a final step in setting U.S. policy that could reignite at least one case where a judge ruled in favor of insurance companies because the term “genocide” was not official.

On a rainy May 4, 2021, a few dozen from the Boston-area Turkish community gathered at the vacant house at 32 Webster Ave. to hold a vigil. The spot where Orhan’s car came to rest serves as a soon-to-be-razed landmark for the Turkish community.

Boston Consul General Ceylan Ӧzen Erişen later emailed the statement she made to the crowd.

“Yesterday the attacker’s weapon was terrorism,” it read. “Today it is political opportunism. But whatever weapon is being used, they forget one thing: truth, just like the sun and the moon, cannot run away from eyesight for very long. I believe, from the depth of my heart, that sooner or later, truth will be done justice.”

Somerville’s once troubled reputation has faded amid waves of gentrification and an influx of new residents, many of whom are unaware of the history that unfolded in front of the now dilapidated building. Union Square and the area of Gündüz’s attack are undergoing massive redevelopment centered around the recent opening of the MBTA’s Green Line Extension. The Union Square transit stop sits just steps away from the spot where Orhan’s car rolled to a halt. Emails released to MuckRock show that a request from Turkish community members for Somerville’s mayor to attend the ceremony and for a proclamation was the first time Mayor Katjana Ballantyne had heard of the incident.

The streets and landmarks of the crime —even the Dunkin’ Donuts where a witness allegedly interacted with the shooter earlier in the day and where Somerville police officers sat when gunshots broke out—will soon never look the same.

Those who knew Gündüz — his family, friends and colleagues in the diplomatic community — did not forget. Nor would the broader Turkish community. Gündüz’s murder would take on a martyr’s significance for Turks in Boston and globally as part of the a 12-year period in which JCAG operated.

For Gonca Sönmez-Poole, an Emerson College undergrad and mentee of Gündüz’s who went on to become a broadcast journalist, the official Turkish denial of reality became clear. In a 2015 interview, she recalled the process of facing the facts that the Justice Commandos violently brought to her attention.

“I remember the guy’s face who came in and said, ‘They shot Orhan-bey.’ But am I going to sit here and say, ‘Look at me, I was really traumatized,’ versus a government killing and deporting a million people into the desert? No, I’m not. It’s just not the same thing.”

Popular Turkish journalist and writer Hrant Dink used the word genocide in his call for reconciliation. His assassination in Istanbul in 2007 earned him recognition throughout the world, including Boston’s Armenian diaspora. Dink’s bravery in speaking frankly about his country’s history also inspired Sönmez-Poole to write about her experience as a Turk confronting the reality of the genocide. She has been working on a film and collaborative project that approaches the subject, Neighbors in Memory.

“The vocabulary has changed, the tone has changed,” she said. “Even though that may seem superfluous to some people, I think it’s important.”

‘I am home’

For Hampig Sassounian, the only person convicted of a JCAG assassination on U.S. soil, spending his life in California prisons also brought a change in vocabulary. In 2002, Sassounian struck a deal. By admitting he killed Arikan, parole became a possibility.

By this point, Sassounian had been incarcerated for two decades. He still had widespread support among Armenian-Americans, especially in Los Angeles. And this was now a multigenerational battle of its own —Geragos’ father, Paul, had represented Berberian of the L.A. Five and Sassounian in the original trial while Mark was still in law school. Mark later took over Sassounian’s parole case.

Geragos appeared before the California Board of Parole Hearings with Sassounian in 2006, when Sassounian described being a young, angry teen who was going to travel to Europe with a friend to attack a Turkish official until he heard that Arikan made statements denying the genocide. He said he trailed Arikan for a day, then went to a liquor store on Hollywood Boulevard to help his nerves before they waited for Arikan to leave for work.

Sassounian said it took 10 years for him to regret what he had done. Asked if he still felt hatred toward Turks, he said, “I just feel sorry for them that they would lie to their own people about their own history.”

This wasn’t enough for the board, who voted against his release. Sassounian’s first successful parole hearing occurred in 2016, where he offered: “There is no justification whatsoever. I was stupid. I was wrong. I was in denial. And I’m ashamed of what I did. There is nothing I can say.”

Asked for an interview in 2017, Sassounian declined our request. “If you ask me, you should do a story about Turkey and the changes taking place there,” he replied via handwritten letter. “I am not that interesting of a person.”

After granting his parole request—nearly two decades after the possibility emerged—California Gov. Jerry Brown stepped in to deny the bid. It took four more years before a judge ruled that the governor’s denial was not valid.

Shortly after a March 11, 2021 hearing, Sassounian was released. He was in Armenia by the end of October, declaring: “I am home.”

Geragos said that Sassounian’s release was past due. Responding to the State Department statement, he offered a truism famously quoted by Reagan: “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.”

“The fact that it took 20 years is mind-boggling to me,” Geragos said, adding that California’s current and most recent governor deserve much of the blame. Brown halted Sassounian’s parole in 2017, while Newsom had done the same in 2020 following more hearings.

“I was a supporter of Jerry Brown and I considered him a friend, and I have not spoken to him since,” Geragos said. “All I can say is, thank God for the recall vote or Newsom would have kept fighting it.”

California governors were not the only officials looking to stop Sassounian’s controversial release. Turkish groups lobbied on the opposite side of Armenian-American groups, maintaining that he has shown no remorse in spite of his statements.

“In a period when hate crimes are on the rise and international solidarity is most needed, release of a brutal murderer with political motivations harms the spirit of cooperation in fight against terrorism,” the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs said in a March 2021 statement.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken also issued a statement criticizing the decision: “Attacking a diplomat is not only a grave crime against a particular individual, it is also an attack on diplomacy itself.”

State Department records released to MuckRock offer additional context about why such a statement might have felt necessary. A Turkish request from 1985 for additional security resources included a recounted interaction with the Turkish Ambassador who noted that, “The Turkish Government, in spite of its limited economic means, does everything it can to protect the U.S. Mission in Turkey.”

Sassounian finally gave an English-language interview on an AYF podcast in September 2022. The youth league of the ARF has maintained active support for Sassounian since he was a member four decades ago. The podcast host recalls writing to Sassounian as part of his own AYF childhood.

Asked what inspired “the movement” of the ‘70s and ‘80s, Sassounian was less circumspect than during his parole board testimony.

“I want to take this opportunity to talk about Koko,” Sassounian said, referring to Krikor Saliba, his accomplice in Arikan’s killing who reportedly died after fleeing to Lebanon. “He’s my hero.”

Sassounian then revealed a freshly inked tattoo honoring Saliba, copied from Saliba’s sister.

Addressing “the movement,” Sassounian was blunt: “These young guys said, ‘You guys did something terrible to me and you don’t want to peacefully talk about it? Well, violence comes next.’ You hear about ‘terrorist this and terrorist that’ from Europe and America. And, you know, if you read their history, they did the exact same shit we did.”

The podcast host later chimed in: “One person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter, right?”

‘I knew he didn’t abandon me’

For friends, family and others who have reflected on Orhan’s death, the killing was an expected but confusing punctuation mark on the intimidation that preceded it.

Speaking to the Boston Herald after the L.A. Five were apprehended, Meral Gündüz said she continued to struggle with her husband being killed as vengeance for the genocide: “I’m having a hard time, especially trying to explain it all to my son.”

Doğan Gündüz had been at a Boy Scouts meeting when his worst fear was realized. When his older brother, Ferdi, showed up, he knew immediately that something was wrong. Later, his brother broke the news.

“I think God prepared me,” Doğan said in a 2021 interview, specifying that he now identifies as Christian and came to his faith on his own after growing up in a “multicultural and multilingual” home. “The shock sets in later. You have those moments of despair and loss and abandonment. I knew he didn’t abandon me.”

After 40 years, Doğan insists his father’s memory looms larger than the footnote he plays in a century-long struggle. His mother died in 2012 and would never get to see justice for her late husband.

“My father was sacrificial. He was honorable. He held absolute truths. He was steadfast, but he was also lovable. He was touchable. He was palpable. When you were in his presence you could feel his love. You felt his bear hug. So he was not one of these figureheads that people just looked at. He was the real deal.”

“You’re never free of it,” Doğan said, describing the lingering grief. “You just live with it.”

For the convicted members of the L.A. Five, life seemed to take a different trajectory. Steven Dadaian went on to become a lawyer and a board member of the Armenian National Committee Western Region. Viken Hovsepian earned U.S. citizenship and was noted as a “a role model amongst youth groups and student groups, to which he frequently lectures about the counter-productiveness of violence,” during appellate court proceedings. Yacoubian, a former principal at the Rose and Alex Pilibos school—the same school which the FBI had obtained the attendance records of in 1985 in connection with the Gündüz shooting— has maintained a private therapy practice and has served as an ARF board member. He earned his U.S. citizenship from a judge in 2000, which the U.S. government appealed unsuccessfully. His conviction in the Fauxbom plot was expunged under the Federal Youth Corrections Act.

Yacoubian did not respond to interview requests. In a 2007 interview as president of the Pilibos School, he told NPR his feelings about a Congressional push for Armenian genocide recognition. It does not mention his role in the Fauxbom plot.

“For us, it’s not an issue of 90 years or 100 years, but it is part of the fabric of our cultural identity,” he said.

Echoing his father’s 1982 testimony about a son obsessed with the genocide, he added: “We don’t feel like this is something that has happened to our grandparents. We feel that this is something that has happened to us. Part of the reason for that is the denial, actually.”

Sarkissian also did not respond to interview requests. He maintains a social media presence that highlights concerts from across the Armenian diaspora. Among his most performed songs is a tribute to the Lisbon Five, who were killed while attacking the Turkish embassy in Portugal.

The 2019 drug distribution charges were Sarkissian’s most recent encounter with the justice system. Unlike the other defendants appearing on the May 24, 2022 court docket, who appeared in orange uniforms, Sarkissian wore a dark blue suit with starched white shirt cuffs and a gold watch. His long flowing hair had been tied back, paired with a neatly trimmed beard and horn-rimmed glasses. His son, dressed in a hoodie, sat with him in the back row until his name was called.

As his hearing ended—with a warning that any parole violation would see him back in Virginia—Sarkissian met a sheriff’s deputy at the front of the galley to be fingerprinted and swabbed for DNA. Leaning against the railing, Sarkissian pressed his thumb into an inkpad. He then opened his mouth for the deputy to insert a cue tip. As the deputy placed it in a green envelope, Sarkissian walked out of the courthouse.

If you are interested in sharing your experience of the events described in this series, please fill out this form to reach the reporters.