Most people have heard of Washington’s revolving door, which allows politicos to cash in on their government service by roving between the private and public sectors, leveraging their government connections and know-how. Distaste for the revolving door, and the potential conflicts of interest it creates, is one of the few things that can unify Republicans and Democrats. Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden both enacted rules to try to limit those interested in passing through the revolving door.

Yet officials on both sides of the aisle have also taken advantage of the revolving door. A first-of- its-kind analysis, conducted by Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation, MuckRock and Forbes, identified 151 officials who left the government in the final days of the Obama administration, then returned under Biden. We were able to track down before- and-after sets of financial disclosures for 77 of those officials, allowing us to see how their personal finances changed when they passed through the revolving door.

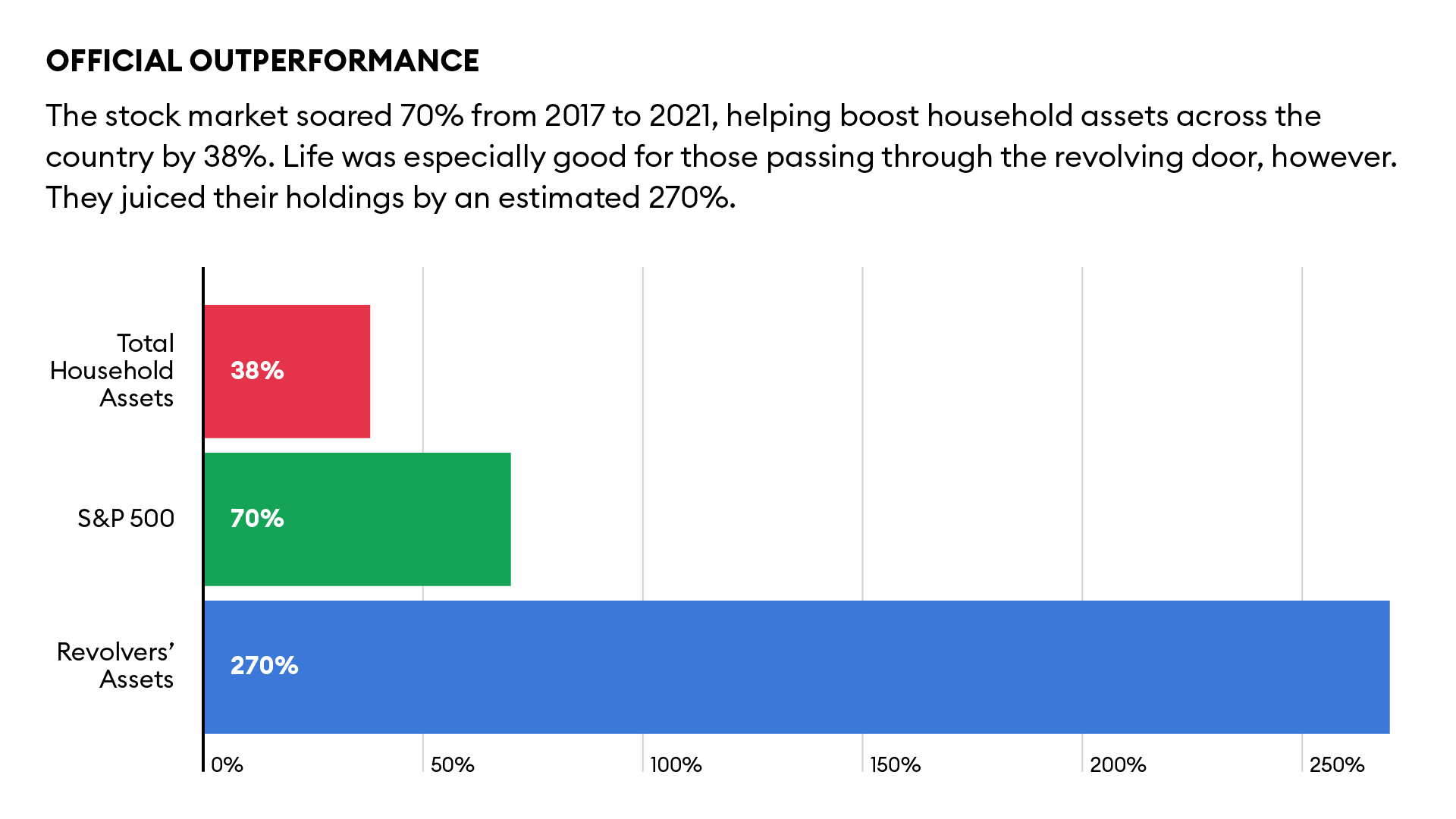

The data is clear. The officials’ median assets increased an estimated 270% over four years. By comparison, total household assets increased 38% nationwide from 2017 to 2021, according to data published by the Federal Reserve. The S&P 500 went up 70% over the same period. The figures highlight why it’s so tempting for public officials to leverage their government experience for private gain. “This shows what the revolving door is all about,” says Craig Holman of Public Citizen, a left-leaning think tank that advocates for corporate accountability and lobbying reform. “People swing through the revolving door to enhance their personal wealth.”

Walter Shaub, who served as director of the U.S. Office of Government Ethics during the Obama and Trump administrations, came to the same conclusion: “In any one official’s case, there might be an explanation. But it’s hard to believe there is an explanation for all [77] of them.”

Boiled down, the revolvers followed three basic formulas. The first: Joining a big company and earning a big salary. Consider Sameer Punyani, who started his career as a 23-year-old staffer on Obama’s 2008 campaign before joining the Department of Defense and, in 2017, jumping to defense contractor Booz Allen Hamilton. Punyani eventually earned $293,000 as a lead associate at the company. His wife, Bhavna Changrani, also worked for Booz Allen Hamilton as a lawyer. In 2017, they reported less than $15,000 in retirement savings. But by 2021, they had built up an investment portfolio of $293,000 to $970,000, according to their financial disclosure reports, which list assets in broad ranges. Property records show that the couple also upgraded their $465,000 Washington apartment to a $900,000 townhouse in 2020. Asked about their finances, Punyani declined to comment.

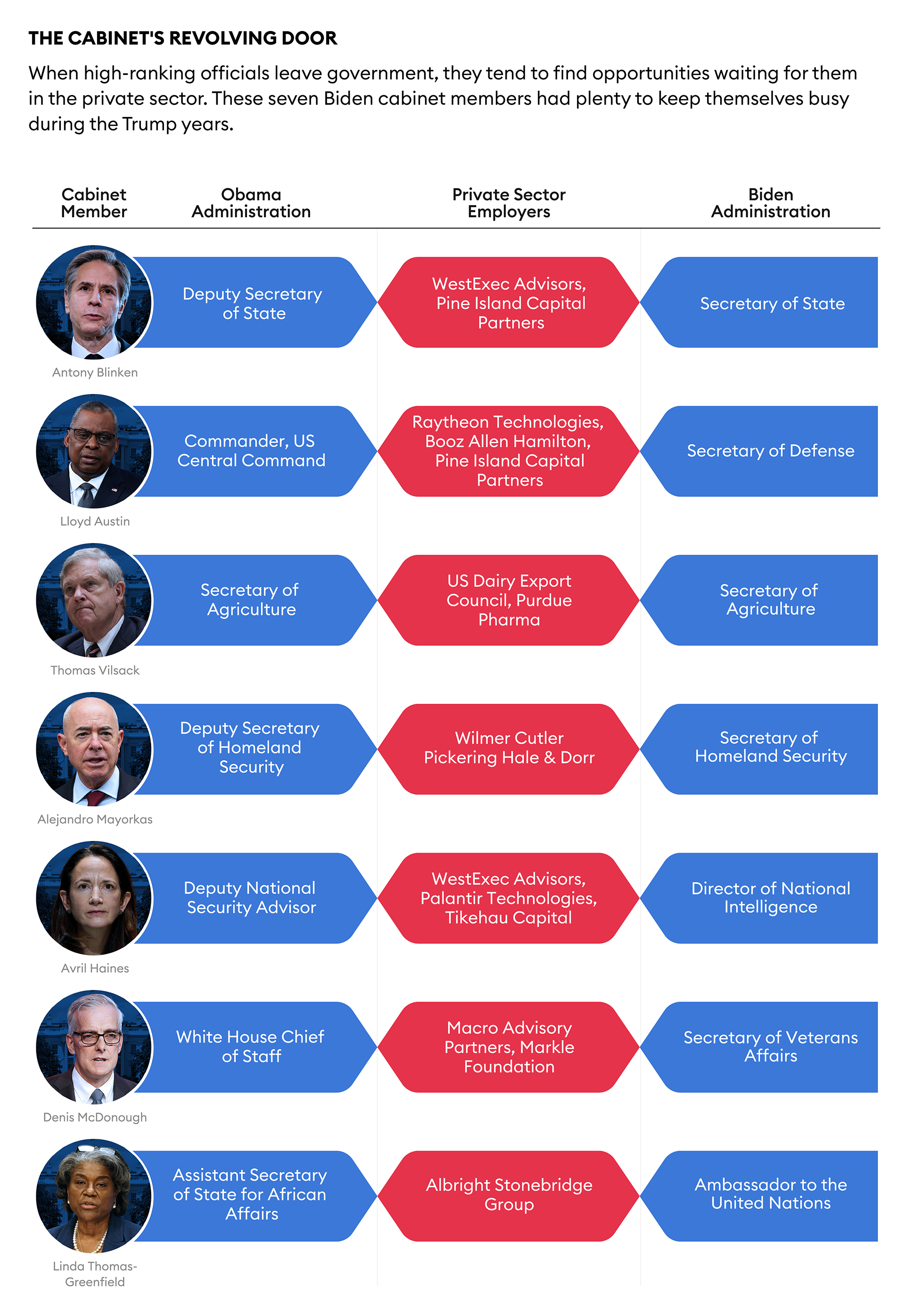

It’s not just mid-level employees who benefit from the revolving door. Between his tenure as a four-star general and the U.S. Secretary of Defense, Lloyd Austin joined the boards of Raytheon Technologies, Nucor Corp. and Tenet Healthcare, earning more than $1 million in cash and $2 million in equity grants. In 2018, he and his wife purchased a $2.6 million home outside the nation’s capital, now part of their roughly $7 million fortune. Representatives for the Department of Defense did not respond to requests for comment.

Those who don’t work directly for a big company can join a law or lobbying firm. Beth George, a lawyer in the defense and justice departments under Obama, advised senior officials on national security and policy issues. Then she headed to Silicon Valley, where she joined Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati. In 2020, she earned $1.8 million, working with companies like Google, Twitter and Snap. George briefly served as the acting general counsel for the Department of Defense in 2021, before returning to the more lucrative world of private practice. George did not respond to a request for comment.

Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas left the Obama administration in 2016 to join WilmerHale, a powerful firm in D.C. Over the next four years, he worked with clients like MGM Resorts, Blackstone and Northrup Grumman. When Mayorkas rejoined the government last year, he disclosed a $3.3 million partnership share, plus a payment of $1 million or more still due to him. No one in our analysis reported receiving quite as much from a law firm as Mayorkas, who is now worth an estimated $8 million. His representatives in the Department of Homeland Security did not respond to a request for comment.

The third route through the revolving door: starting your own shop. James O’Brien, Biden’s coordinator for sanctions policy, led the European practice at international advisory firm Albright Stonebridge while he was out of government. The state department underscored O’Brien’s resume, which includes working on sanctions programs for the United States and the United Nations, as well as serving as a special presidential envoy on two occasions. “Jim O’Brien’s qualifications speak for themselves,” a spokesperson said in a statement. O’Brien’s former firm has sent more than a dozen of its alumni into the administration, raising concerns about its influence within the government. The State Department spokesperson refused to be identified providing additional information about O’Brien’s work at Albright Stonebridge.

The same concerns surround WestExec Advisors, a strategic consulting firm that Secretary of State Antony Blinken cofounded in 2017. Working with clients such as FedEx, Blackstone and Uber, Blinken grew the firm quickly. In 2018, he and his wife Evan Ryan—also a former Obama and current Biden employee—bought a $4.3 million house outside of D.C. Three years later, as secretary of state, he listed $1.2 million of guaranteed payments and distributions from WestExec, as well as over $1.5 million of investments connected to the firm. He’s now worth an estimated $10 million. “Secretary Blinken has made clear that we adhere to the strictest ethical standards and that our only consideration will be in the national interest,” Ned Price, a spokesperson for the State Department, said in a statement. “Every State Department official will abide by applicable disclosure requirements and strict ethics rules, including recusals when appropriate. That, of course, includes the secretary.”

Adherence to ethics restraints doesn’t always preclude making money via the revolving door. “Government insiders can sell understanding of the government at a high rate,” says Jeff Hauser, who scrutinizes the revolving door through his work at a left-leaning think tank called the Center for Economic Policy and Research. “It does not matter if they take on the name lobbyist, consultant, attorney or strategic advisor.”

Representatives of the Small Business Administration, office of the Director of National Intelligence, White House and State Department said in statements that their employees face routine and stringent ethics requirements while in office. On the day he became president, Biden issued an executive order that banned officials from working on some issues, like regulations and contracts, that are directly related to their former employers and clients. “President Biden has established the highest ethical standards of any administration in history,” the White House said in a statement.

The ban, however, only applies to cases where a personal service has been provided to the company in question, which also has to be a named party in the policy discussion. In reality, much of what a corporation wants from the government is more abstract—for example, broad tax relief or general trade policy. Biden’s ethics advisors don’t “think like people who are trying to follow the spirit of the rules,” says Shaub, the former ethics director, who has been in touch with White House officials over the past year. “They think like lawyers who are trying to literally follow rules.”

Methodology

In partnership with Forbes, Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation and MuckRock identified 151 “revolving door” government officials who left the Obama administration after 2016, worked in the private sector and returned under the Biden administration in 2021. The disclosures were parsed using an open-source tool developed by the Center for Public Integrity and then cleaned the data using the programming language R.

In public financial disclosures, each asset’s valuation is disclosed as a range, such as “$1,001 to $15,000” or “$15,001 to $50,000.” The true valuation of the asset is somewhere within the range. Sometimes there is no upper limit, such as when certain assets are listed as “over $1 million.” Therefore, most computational findings in this story are based on lower minimum amounts. To arrive at the 270% estimate, for example, the percentage increase of each individual’s reported minimum asset amount was calculated from 2017 to 2021.

An increase in reported minimum asset value does not necessarily indicate that someone became wealthier. But compared to the largest possible amounts, the minimum amounts are more consistent indicators of wealth. The differences between reported minimum assets are not meant to precisely estimate changes in any individual’s net assets. Instead, they point to an aggregate pattern—that most officials became significantly wealthier after going through the revolving door.